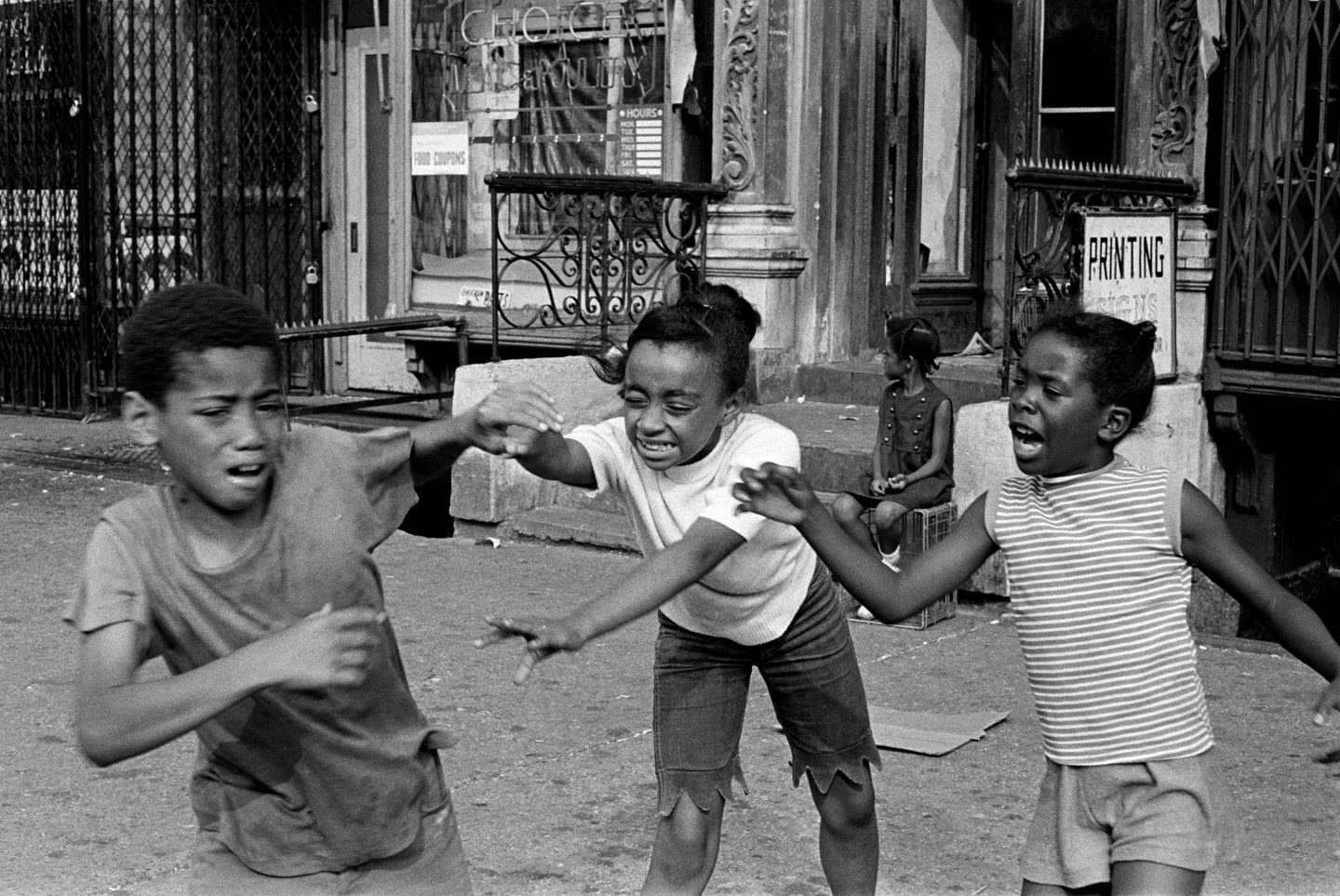

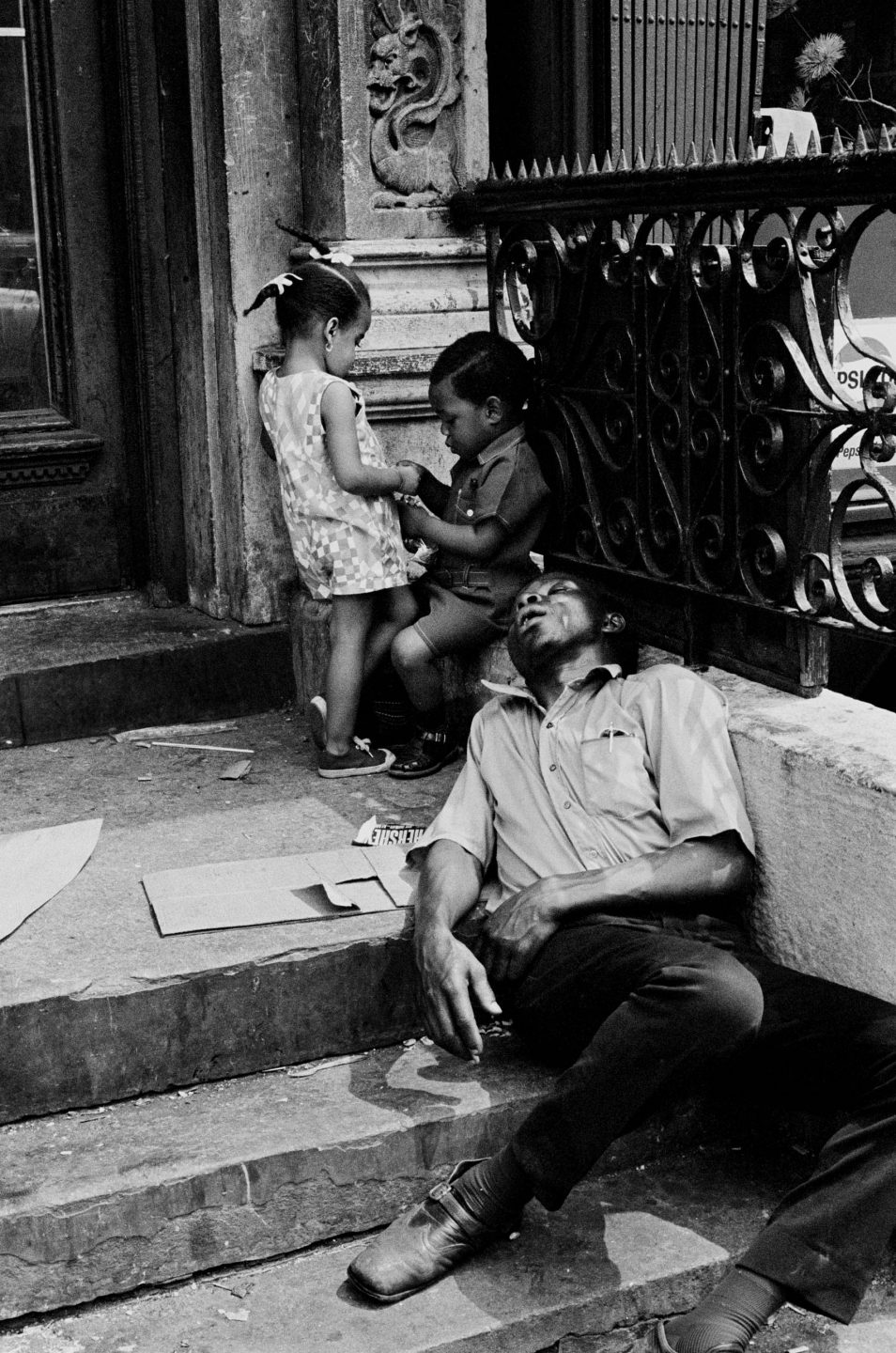

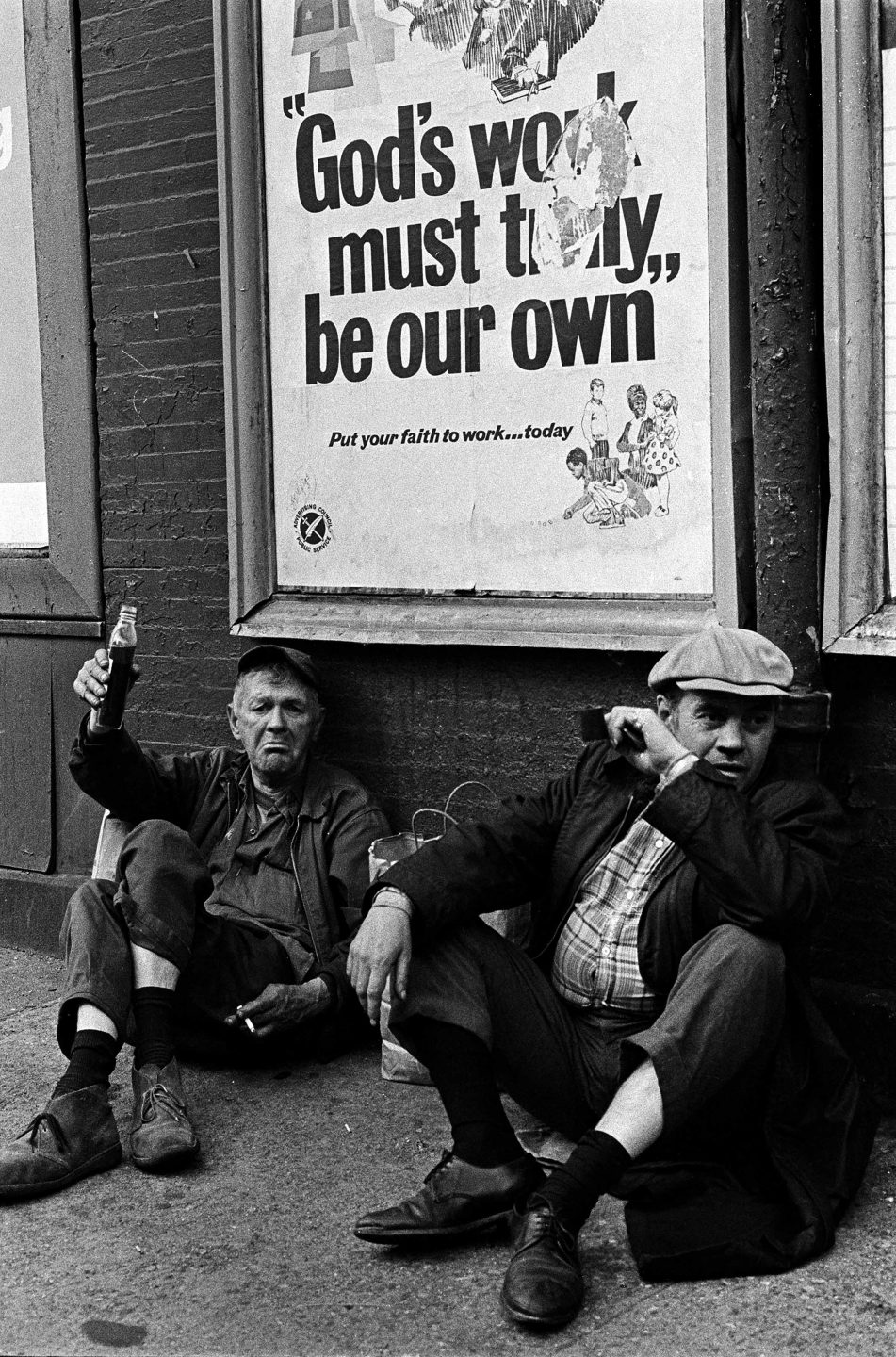

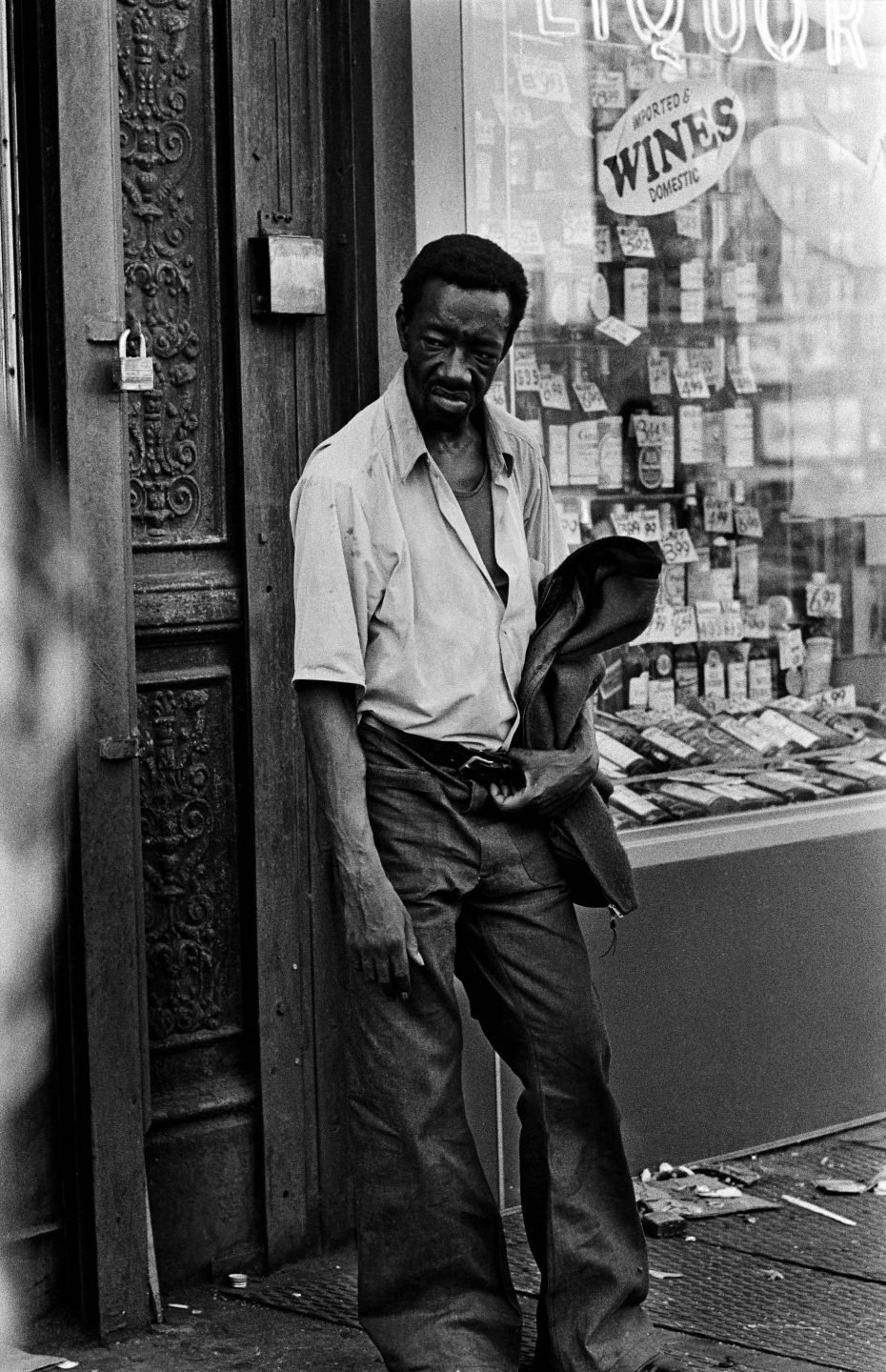

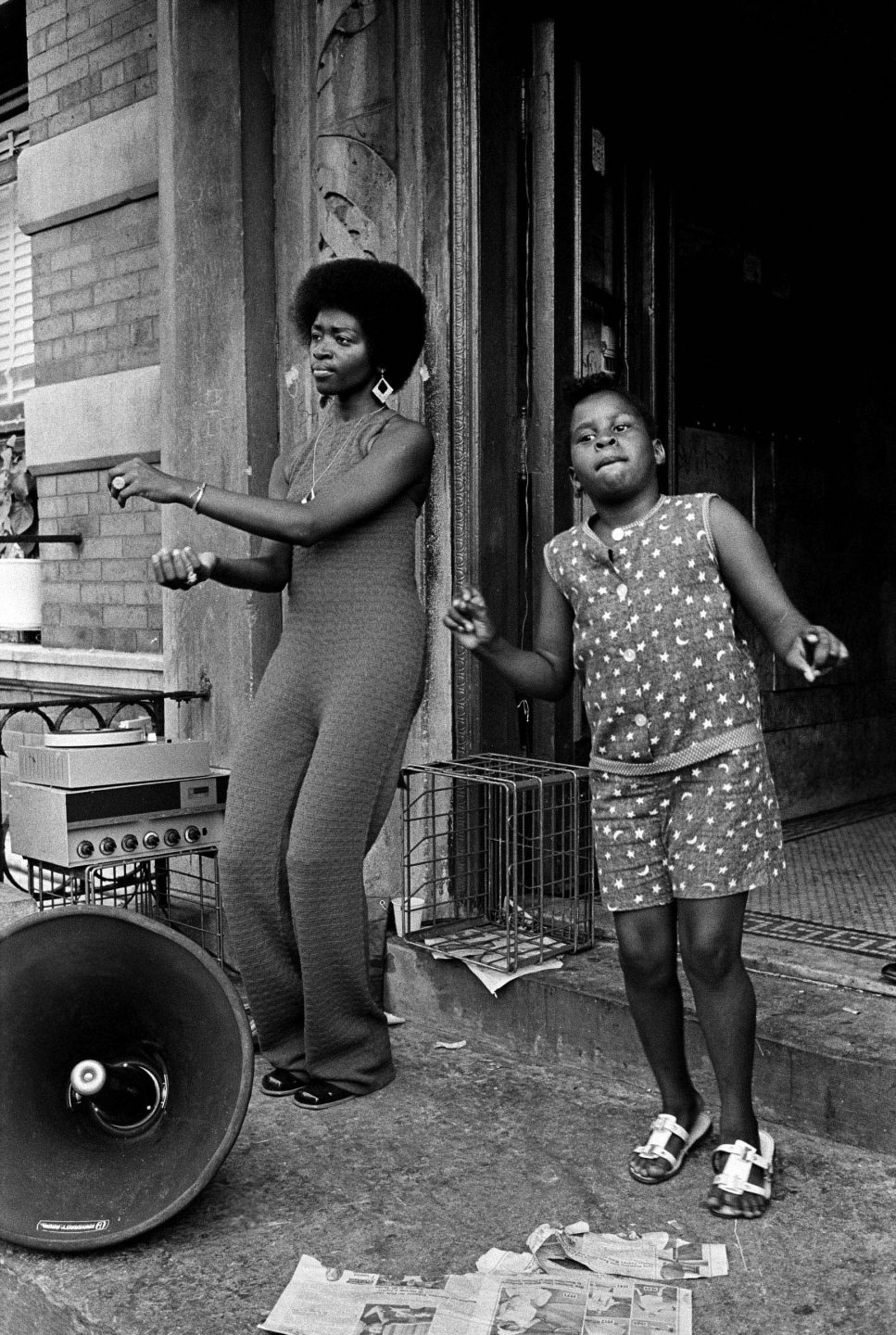

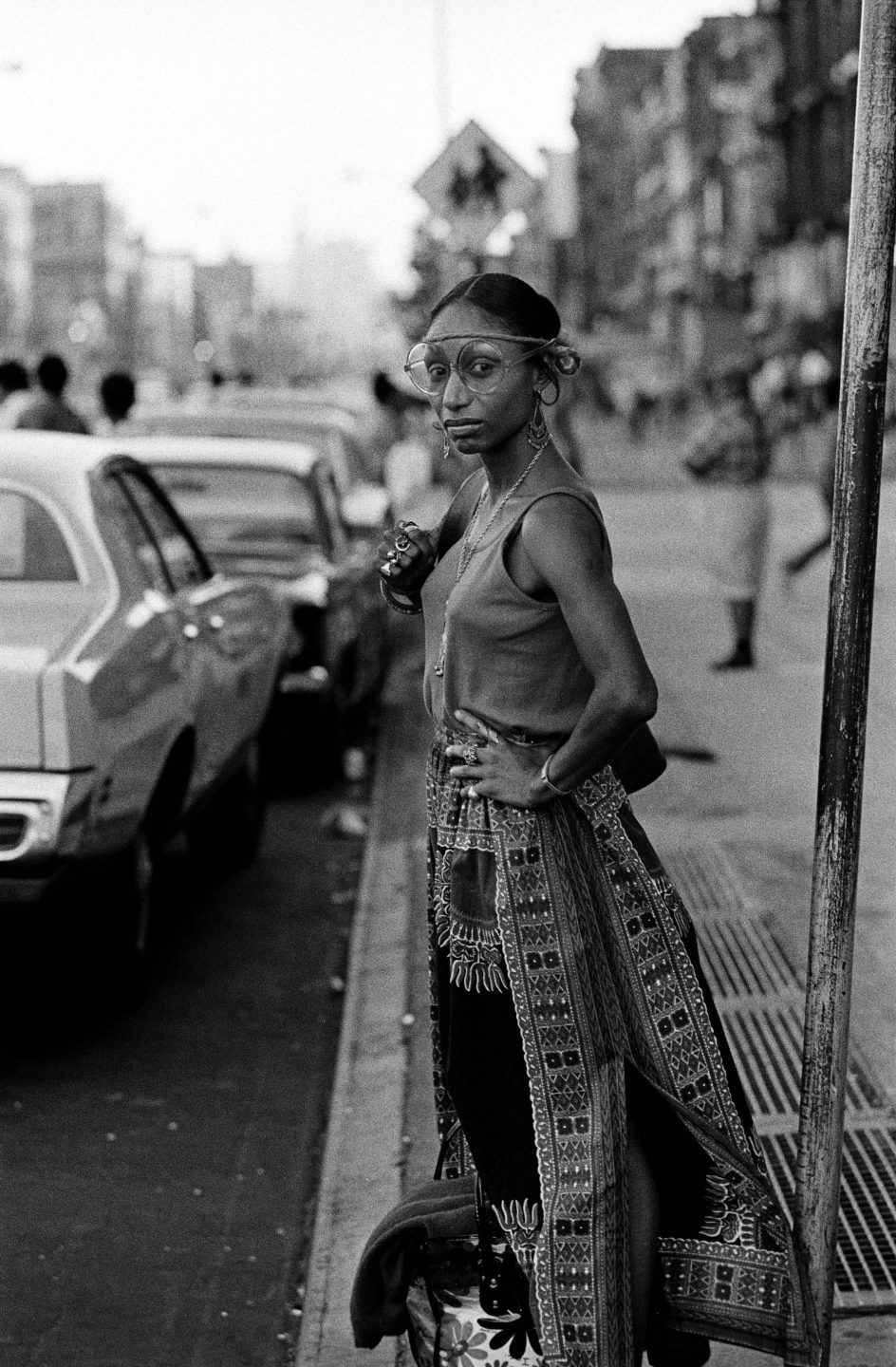

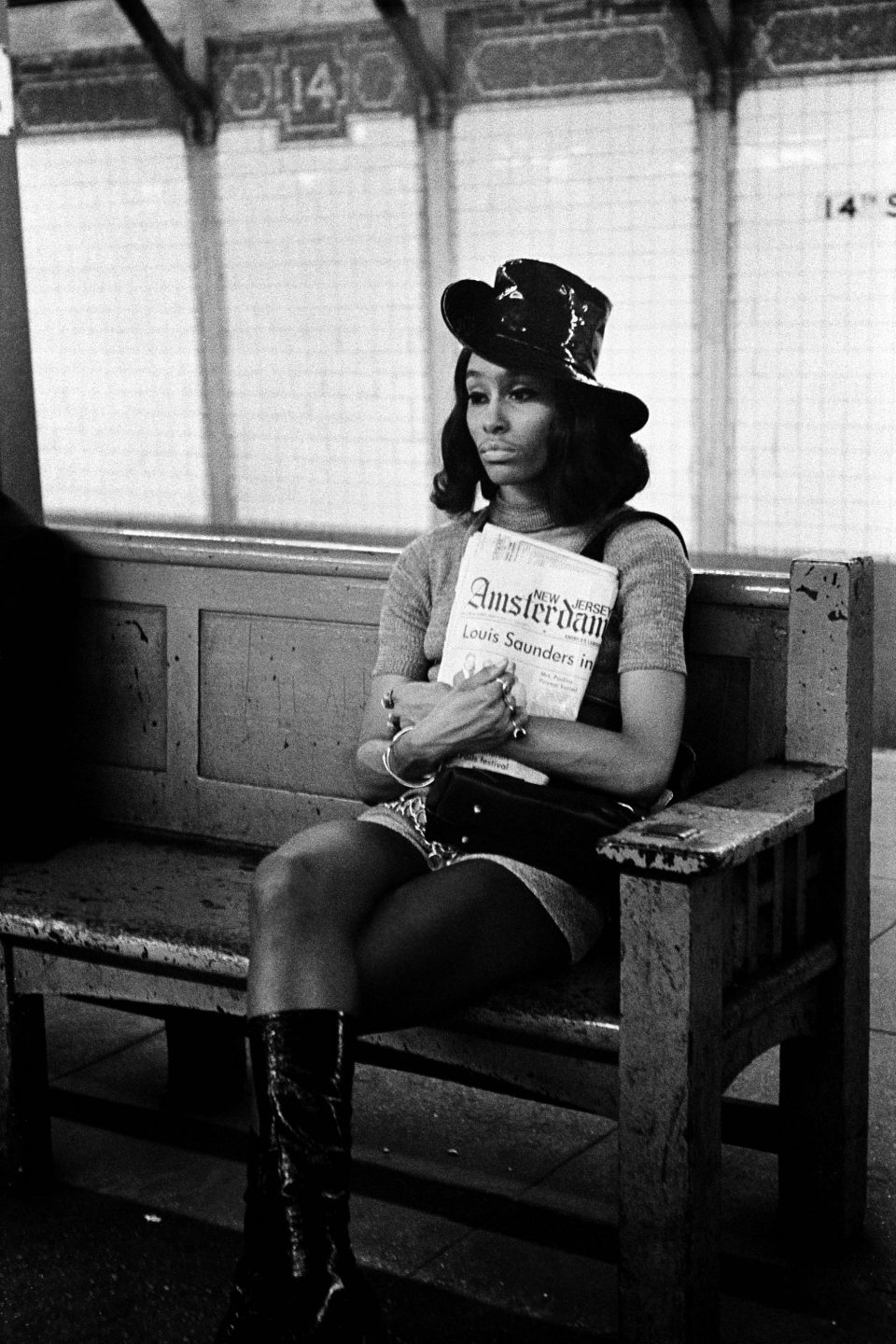

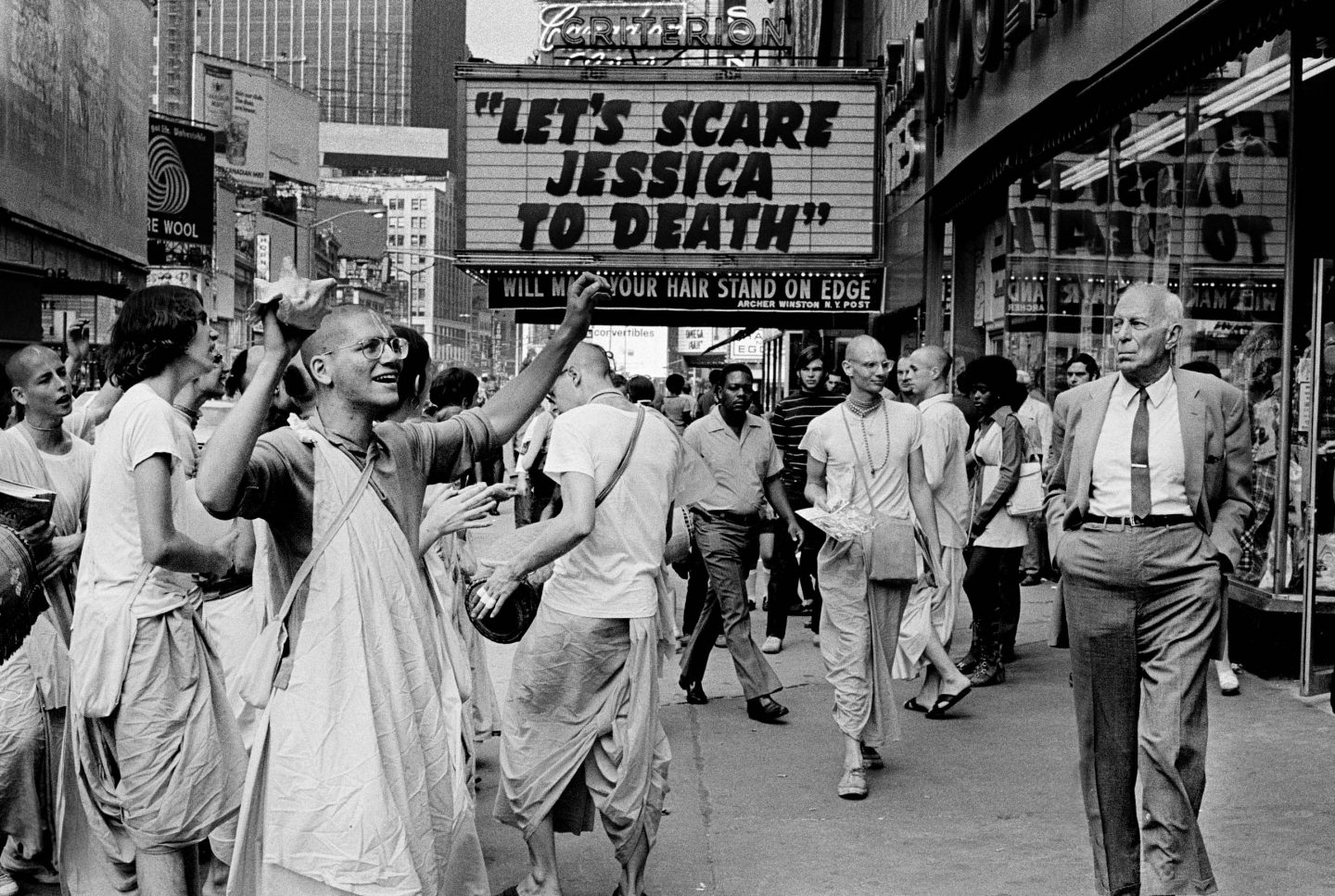

Ernest Cole’s unseen photographs

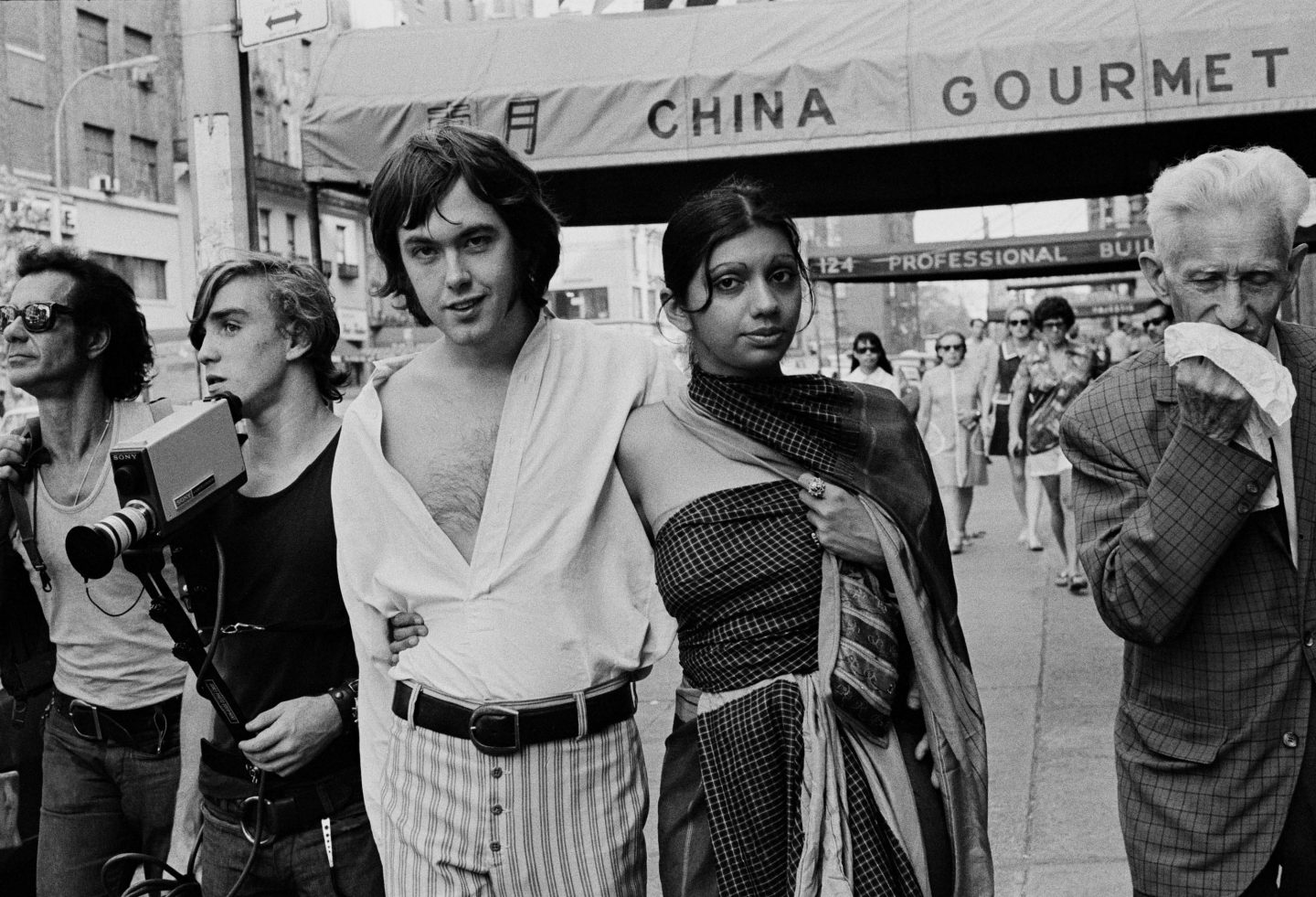

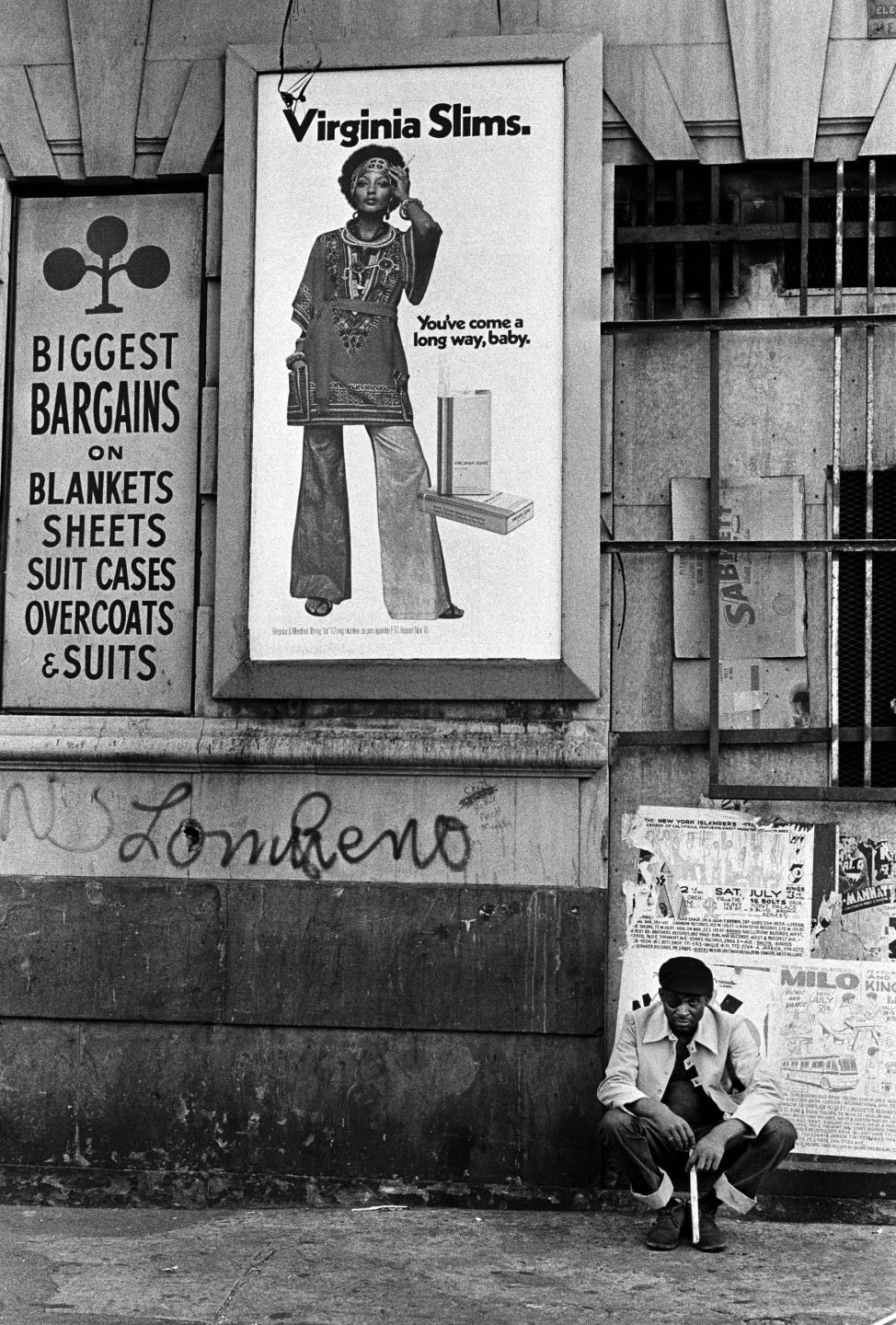

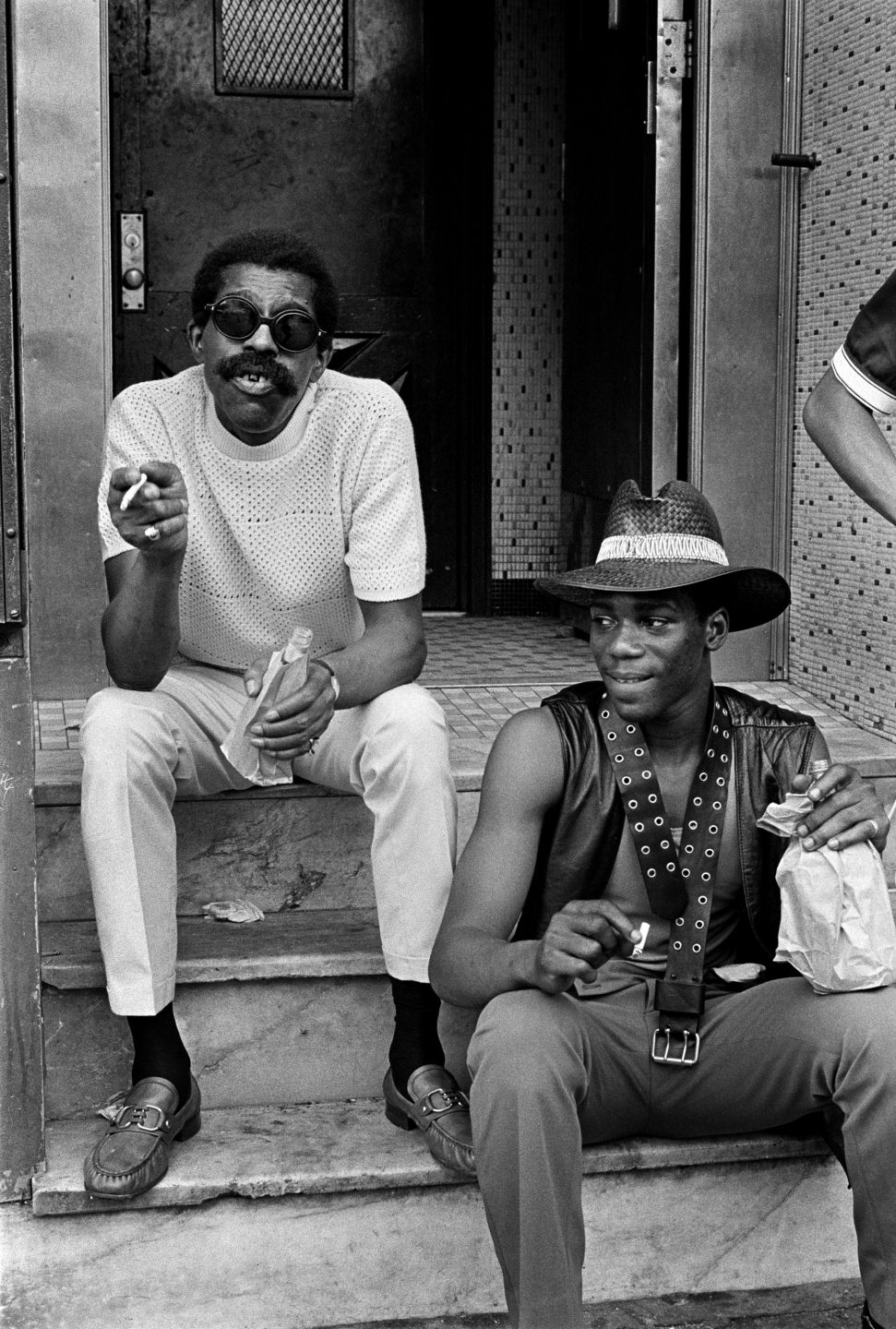

An exclusive gallery of recently discovered photos from the work Ernest Cole did for the Ford Foundation, focusing on the experiences of urban and rural African Americans.

Author:

21 August 2020

Ernest Levi Tsoloane Kole was born in 1940 in Eersterust outside Pretoria. He and his family were later forcibly removed to Mamelodi.

Kole was raised as a Catholic and attended a Catholic school before leaving at the age of 16, disgusted by the introduction of the Bantu Education policies of the apartheid regime. He completed his education via correspondence through Wolsey Hall Oxford, a homeschooling college in the United Kingdom.

In 1958 at the age of 18, Kole, who had begun to practise as an amateur photographer, approached Drum magazine chief photographer Jürgen Schadeberg for a job. Schadeberg took him on as an assistant and Kole improved his photographic skills through a correspondence course with the Institute of Photography in New York in the United States. Encouraged by the institute and inspired by his meetings with the black photographers of Drum – such as Peter Magubane, Bob Gosani and Alf Kumalo – Kole soon began to make a name for himself. He became the country’s first black freelance photographer, with his work appearing in Drum and the Rand Daily Mail, The World and Sunday Express newspapers from the early 1960s.

To increase his access to various areas and work more freely within the confines of racial segregation and the pass laws, Kole changed his name to Cole and applied for and was granted reclassification as a coloured person under the apartheid racial classification system. However, Cole was still unable to avoid intimidation and interrogation by the security police, and in 1966 he applied for a passport to leave South Africa under the guise of making a pilgrimage to the Catholic holy site of Lourdes in France.

He took with him the negatives of the work that would be published in 1967 as his seminal book House of Bondage. Soon after the publication of the book, Cole was given a grant by the Ford Foundation in the US to produce two series of work looking at the black American experience in the urban centres and rural areas of the country. It is from this work that the images in this gallery have been drawn, although no pictures were delivered to the Ford Foundation, exhibited or published in Cole’s lifetime.

Related article:

It is known by the anecdotal accounts of South African exiles such as musician Abdullah Ibrahim, photographer Rashid Vally, the late poet laureate Keorapetse Kgositsile and others that Cole lived in New York for most of his time in exile and regularly visited Sweden during the late 1960s and early 1970s. It is also through these anecdotes that we know he produced work as part of the commission for the Ford Foundation, but no one seems to have ever seen these images or know what Cole did with them.

The record that has been pieced together of Cole’s later years – leading up to his death in New York from pancreatic cancer in 1990, just days after the release of Nelson Mandela and following a final bedside visit from his mother and sister – is sketchy, based on contradictory accounts and stories told by former exiles and photographers. But what has emerged is a picture of a man who lived an often desperate hand-to-mouth existence, one who seemed to have become disheartened by life in exile. When he died, no new work by Cole had been seen in more than two decades and the location of his photographic archive was unknown.

Now that the images from the bank vault in Sweden, handed over to his nephew Leslie Matlaisane in 2017, have begun to be scanned and released, it is evident that Cole was keenly focused on his Ford Foundation commissions and the many expressions of political and sexual freedom he saw all around him. The photos seem to be predominantly from the streets of New York. They display the work of a photographer looking to expand his horizons while being acutely shaped by his experiences as a victim of apartheid and its oppressive humiliations and restrictions.

Related article:

There is little in the way of captions or Cole’s thoughts about the work he was producing, but the images stand on their own, distinctively capturing a particularly complex moment in the history of the US. They show hope and exuberance in the wake of civil rights gains and the utopian optimism of the psychedelic era living side by side with the harsh realities of racial economic inequalities of African Americans, both urban and rural. All this has been smartly encapsulated by the ever-curious lens of Cole’s camera.

What the American political and photographic circles of the time may have made of them during that moment will sadly never be known. But here they are, almost 40 years later, for the world to see. And that is something to celebrate, because whatever else he was and may have later become, Ernest Cole was always a unique and brilliant photographer.