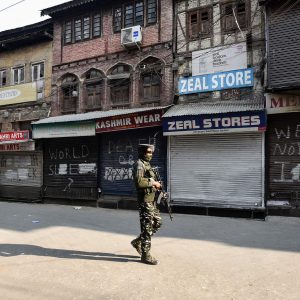

Extreme Hindu nationalists smother dissent in India

The Indian poet Varavara Rao was arrested in 2018 and is still being detained. His treatment is symptomatic of how the right-wing government is waging war on opposition and minority voices.

Author:

1 December 2020

“This life in jail is life crippled –

You can no longer

Apprehend your world

…

Here your mind is an injured eye

That flutters shut”

This is how Varavara Rao, an octogenarian poet, writer and radical activist from the state of Telangana in southeast India, described his experience of imprisonment during the second half of the 1980s, in the essay collection Captive Imagination. Rao was locked up on conspiracy charges connected to his political activism – they were eventually entirely dropped – and kept in solitary confinement from 1985 to 1989. But his lament might as well have been written about the nightmare of carceral persecution he has endured at the hands of Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist regime over the past two years.

Rao was arrested on 28 August 2018 alongside four other activists as part of a nationwide police sweep. The Bhima Koregaon case, as it has come to be known, refers to the police investigation into violence that erupted in the western Indian state of Maharashtra in early January 2018. Dalit groups had gathered to commemorate the bicentennial of the defeat of the upper-caste ruler Peshwa Bajirao II by the armed forces of the British East India Company – a force that also counted a substantial number of Mahars, a Dalit community, in its ranks. They were attacked by a Hindu nationalist mob.

But rather than scrutinising the involvement of Hindu nationalist leaders in the attack, the police investigation targeted prominent activists such as Rao, who were arrested on charges of instigating the violence and planning a terrorist attack on Modi. And the crackdown did not stop there. Sixteen arrests have been made in connection with the case since 2018. Most recently, a Dalit scholar and activist, Anand Teltumbde, was arrested in April this year. Five months later, Father Stan Swamy, a Jesuit priest who has dedicated his life to fighting for the rights of Adivasi groups in the state of Jharkhand in eastern India, was also arrested. The gravity of the charges mean the accused have been refused bail and remain in police custody.

Rao’s imprisonment has been particularly arduous. As Covid-19 began to spread through Indian prisons, Rao’s family reported that his health was declining and prison authorities had failed to give adequate medical attention to the 80-year-old inmate. In late May, he was hospitalised in prison, then transferred to a state hospital after he fell unconscious. He was returned to jail two days later. His application for bail on health grounds was rejected in late June.

Related article:

Rao’s medical condition continued to decline, and when he was once again hospitalised in the middle of July, he tested positive for Covid-19. His diagnosis, however, did not result in judicial respite. Instead, he was sent back to prison in late August. By the middle of November, Rao’s lawyer, Indira Jaising, reported that he had been left to languish in a prison hospital: “He is completely bedridden and has no medical attendant. He is in nappies and has a catheter. The catheter was not changed for three months, as there was no one to change it.” Rao was shifted to a private hospital, but his bail application was once again rejected.

War on dissent

The imprisonment of Rao and the other accused in the Bhima Koregaon case is symptomatic of the governing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its war on dissent in India since Modi was elected in 2014.

The first shots were fired in early 2015, when student activists at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in Delhi were arrested on trumped-up charges of sedition. Although the students were ultimately cleared of all charges and released, the arrests helped spawn the idea that India harbours “anti-national” forces that are undermining the country from within. This has been used to justify a range of coercive attacks on dissidents – including activists, public intellectuals, academics, students, lawyers and journalists – who dare to question a government that claims to be acting in the interests of the Indian people.

Related article:

Legal harassment and public vilification were the chief modus operandi of the state in the early stages of its war on dissent. News channels, for example, that reported critically on the Modi regime found themselves on the receiving end of police raids and investigations. The arrests of Rao and others in 2018 made it evident that the BJP government had scaled up its attack on opponents. After mass protests against anti-Muslim citizenship laws erupted in late 2019, it further escalated its repressive measures. Then the country was hit by the Covid-19 pandemic, and the BJP government imposed one of the most stringent national lockdowns in the world from 24 March this year. Indeed, the lockdown facilitated the war on dissent in Modi’s India in crucial ways.

Curtailing citizenship

In early December 2019, the Indian parliament passed the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). Justified by the Modi government as a humanitarian measure, the CAA makes it possible for religious minorities from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh to obtain Indian citizenship if they can prove that they lived in the country before 31 December 2014. However, the CAA only extends this right to Hindus, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains and Parsis. Muslims are excluded from its remit, a fact that fuelled fears that the CAA would usher in a hierarchy of citizenship in which India’s Muslim minority would occupy a marginal position.

This is especially worrying because the CAA is to be coupled with a National Registry of Citizens (NRC), which makes the right to Indian citizenship depend on whether or not individuals can prove they were born in India between January 1950 and June 1987, or that they are children of bona fide Indian citizens. Many Indians do not have the necessary documents to prove this, but Hindus most who find themselves in this situation can make use of the lifeline offered by the CAA – except for Muslims.

Related article:

The CAA and the NRC met with protests across India. Often spearheaded by Muslims, this groundswell constituted the first substantial nationwide opposition to the policies of the Modi regime since it took power. Protesters faced brutal police actions and arrests, and Hindu nationalist mobs attacked student activists at JNU and groups of demonstrators elsewhere in Delhi. By late February this year, BJP leaders in Delhi incited mobs to attack Muslim neighbourhoods in northeastern parts of the city as part of their campaign against anti-CAA protesters. In the riots that ensued, 53 people – 39 of whom were Muslims – were killed, and hundreds of families were displaced from their homes. Despite the repression and violence, the protests continued until late March, when the national lockdown made it impossible to organise and mobilise on the country’s streets and public spaces.

As protesters retreated, the Delhi police, which reports directly to the central government and the Home Ministry, swung into action, operating under the cover of the national lockdown to persecute leading anti-CAA activists. At the heart of this persecution lies the claim, by the Delhi police, that the violence in Delhi was the result of a carefully planned conspiracy executed by anti-CAA activists. The conspiracy, the police narrative goes, revolved around spreading misinformation about the CAA and the NRC, and then encouraging young Muslims to join street protests. These subversive efforts allegedly reached their climax with the violence in late February, which the police claim was intended to cast India in a negative light in the international media.

Criminalising dissent

A large number of arrests have followed and, as with the accused in the Bhima Koregaon case, charges are framed in terms of involvement in terrorism and sedition, as well as serious offences under the Indian Penal Code such as murder, attempted murder and promoting enmity between different groups. The evidence against the activists is extremely flimsy and evidently fabricated, yet, as a detailed report from the Polis Project, an independent research and journalism organisation, points out, the criminalisation of dissent serves the purpose of silencing citizens. The national lockdown has, of course, made this work easier, as it has been impossible to counter the wave of arrests with fresh waves of protests.

The war on dissent in India is part of the political project that has propelled Modi and the BJP into an unprecedented position of power. The politics of authoritarian populism draws a line between “true Indians” and their enemies – be they anti-national dissidents or stigmatised Muslims – and enlists the support of the Indian people in defeating these enemies within.

Related article:

This political project is doubtless the most serious threat that India’s secular, constitutional democracy has faced since its inception at independence in 1947, and it shows few, if any, signs of wavering in its efforts to constitute India as a Hindu nation under a strongman leader.

More than ever before, then, India’s beleaguered community of activists and public citizens, as well as the country’s vulnerable minorities, need the solidarity of those who value democratic rights as sacrosanct. Indeed, in as bleak a moment as the present, we need to remind ourselves of a more hopeful segment of Rao’s prison writings:

“Held in our fists

Stuck to our palates

Hidden under our eyelids

Rooted in our hearts

Is freedom

Wounded and tremulous,

Freedom nevertheless.”