Fascism spoken softly does not soften its blows

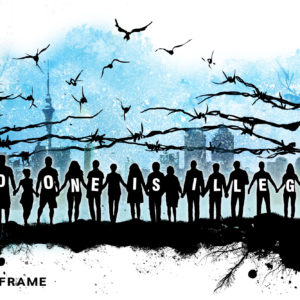

As xenophobic mobilisation escalates, democracy appears increasingly fragile. A new vision of emancipation rooted in a politics of solidarity is needed now more than ever.

Author:

1 April 2022

The broader unemployment rate is 46.2%. Almost two million of the jobs lost in the lockdowns during the severely mishandled Covid-19 crisis have not returned. Millions of young people have no real prospect of ever finding work. Children are starving to death. We are circling, without any sort of collective vision, in the tightening coils of a devastating social catastrophe.

Unions confront an almost impossible situation, constantly organising in crisis mode as deindustrialisation continues. In the last quarter, 85 000 jobs were lost in manufacturing and another 25 000 in construction.

As usual, there is no sense from the government that this is a national disaster, a situation that is likely to result in more riots, more xenophobic violence and the emergence of more authoritarians making bids for popular support.

Related article:

In a crisis of this scale and severity, social disorder is inevitable. Our future will be made, for better or for worse, within the popular alienation from the crumbling authority of the once well-established post-apartheid order. The dominant political form that will emerge from within this popular alienation is yet to be determined.

Will the turning away from the old consensus, and its leaders, lean to the Left and take the form of a new iteration of the sort of mass-based progressive politics that carried us through the 1980s? Will it lean to the Right, perhaps taking on an increasingly organised xenophobia and repeating the horrors of May 2008? Or will it, like the July riots, carry an implicit political logic that, because it is not organised or developed into an explicit set of unifying demands, is open to both obfuscation from above and penetration and exploitation by the worst kinds of opportunists?

Popular democracy

One of the few things that is certain in this situation is that a democratic resolution of the crisis will only be possible through the construction of democratic forms of popular counter-power.

But with various attempts to build authoritarian populism well under way – from the now well-established EFF to newer and quite different players like the Patriotic Alliance and Operation Dudula – there is a real risk that as the social fabric rips it will mostly tear to the Right.

With a government and state that both indulge even increasingly militarised formations organised around violent hostility towards working-class African and Asian migrants, and that steadily incorporate some of the rhetoric of these formations, there is also a real prospect that these new attempts to incite and organise xenophobic hatred will drag the ANC and the state further and further into their orbit.

Related article:

The ANC is entirely unable to address the social catastrophe. It is not even willing to impose the sort of discipline against its predatory currents that would be required to run the railways and hospitals to a basic degree of functionality. The party is in such a deep moral crisis that a figure as compromised as Zweli Mkhize can be seriously considered for its highest office. Cyril Ramaphosa is an increasingly absurd figure, a man not even capable of giving a speech that speaks to the social crisis with honesty and power, let alone generating any sort of meaningful political vision and the means to realise it.

For all these reasons, along with others, the party is heading towards an electoral defeat. If this trajectory holds, the temptation to turn what was once an emancipatory nationalism to utterly reactionary ends to further scapegoat a vulnerable minority for ANC’s own failings will be tremendous.

Functional hatred

Xenophobia is functional for elites, which is why it has so often festered in times of social crisis, including in so many countries across the Global North in recent years, as social democracy gave way to the ravages of neoliberalism. It allows both blame for a crisis and the expression of the social anger it produces to be displaced.

Those who tell us that a Ghanaian cobbler, a Zimbabwean handyman or a Bangladeshi shopkeeper are responsible for the suffering of their neighbours are either delusional or opportunists who are willing to lie for the most cynical reasons. They diminish us all. They also turn us away from the urgent tasks – necessarily entwined tasks – of building the democratic power of the oppressed and developing a political vision adequate to our times.

As xenophobia has become increasingly organised and brazen over the years, a set of increasingly morbid personalities has emerged and sought to build a popular constituency. So far, they have all been men of limited ability, and none of them have been successful. When it comes to building and sustaining popular organisation, someone like S’bu Zikode from Abahlali baseMjondolo, the consistently anti-xenophobic movement of the urban poor, has been vastly more successful.

Related article:

But the latest contender to build and lead an organised xenophobic politics, Nhlanhla “Lux” Dlamini, seems potentially more dangerous than his predecessors. His claim to have communed with Steve Biko in a holding cell is ridiculous, as are his television appearances in camouflage and a bulletproof vest. But fascism is always ridiculous until the moment it becomes terrifying. If Dlamini, with his soft-spoken hatred, is not able to build a xenophobic movement at significant scale, the time will come when someone else will.

If that moment comes, and if it comes to dominate the popular ferment that is already under way and sure to grow, we will have, for at least a generation, consigned ourselves to the end of the progressive aspirations that carried so many through so much for so long.