From the Archive | Paris 1961: a hidden massacre

As the Algerian war for independence neared its end, 30 000 Algerian migrants assembled to oppose police violence in France. They were met with deadly force.

Author:

10 December 2020

This is a lightly edited article, first published by International Socialism: A Quarterly Review of Socialist Theory.

Leaving aside situations of insurrection, revolution or civil war, the massacre of Algerian demonstrators that took place from 17 to 20 October 1961 in Paris constitutes “the bloodiest act of state repression of street protest in Western Europe in modern history”. Jim House and Neil McMaster’s account of 17 October and its complex legacies in Paris 1961: Algerians, State Terror and Memory (Oxford University, 2006) is rich in detail, based upon a combination of extensive research in recently opened state archives, oral sources and secondary literature. The result is a highly significant contribution to the polarised historiography of 17 October, the Left in this debate being represented by Jean-Luc Einaudi and the Right by Jean-Paul Brunet.

Of course, when the state archives were eventually opened in the late 1990s, Brunet was given privileged access some 30 months before Einaudi. He subsequently emerged claiming that only 30 Algerians had been killed and that the events of 17 October could hardly be called a massacre. Such historical controversies are a product of the fact that the French state was, from the outset, successfully able to erase this act of repression from the public vision.

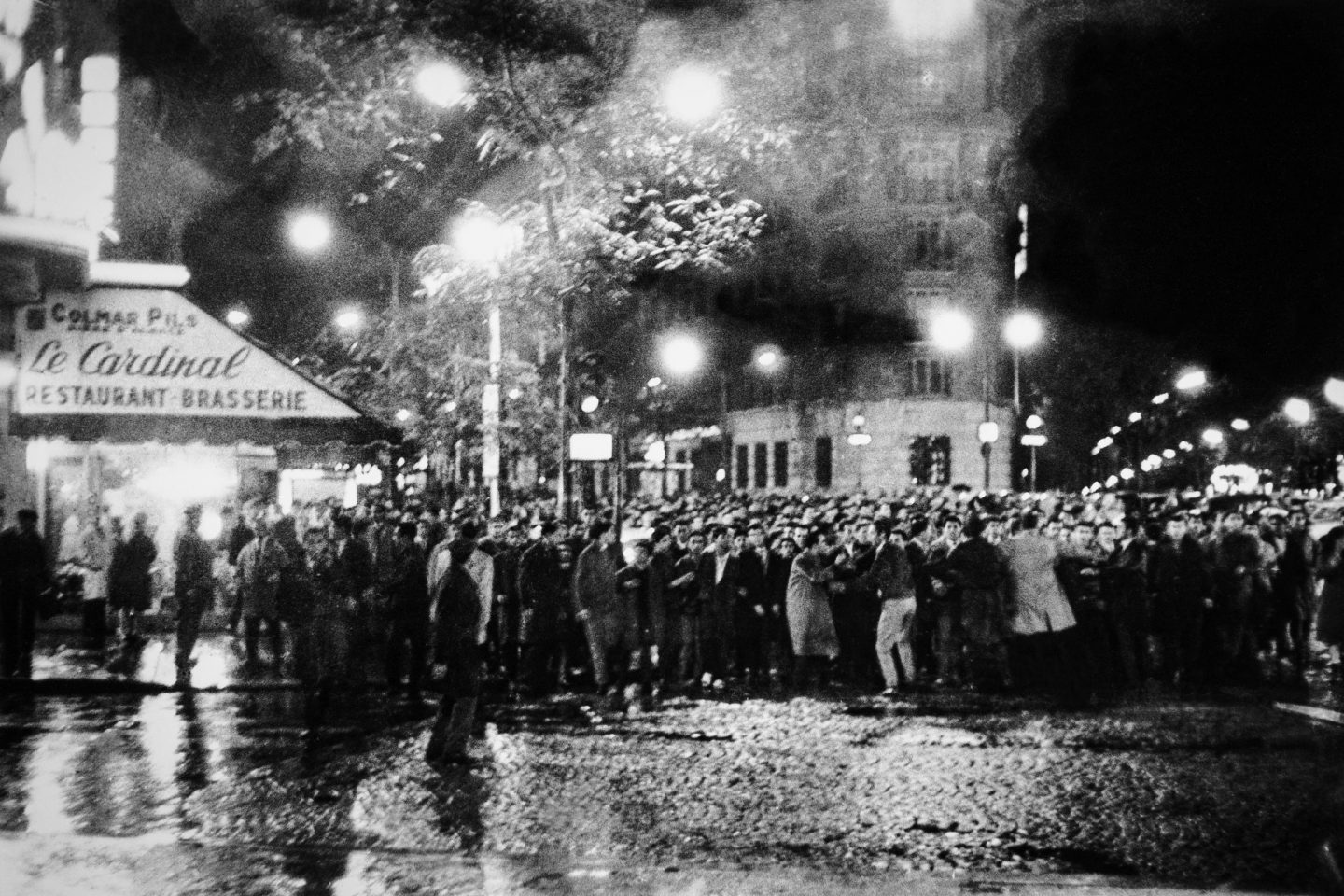

On 17 October 1961, as the Algerian war for independence neared its end, 30 000 Algerian migrants set off from the bidonvilles (shanty towns) to demonstrate in Paris. They assembled to show their support for the Algerian National Liberation Front, and their opposition to a police curfew and rising levels of violence they faced at the hands of the Harkis (pro-French Algerians) and the French police. On arriving in Paris demonstrators were met with extreme violence. Many were either shot or bludgeoned to death, their bodies dumped in the Seine. Meanwhile, thousands of demonstrators were taken to “holding centres” where they faced torture before being deported into the hands of the colonial authorities in Algeria. The police acted as they did confident in the knowledge that they would not be held to account by President Charles de Gaulle or anyone else in the French government.

Maurice Papon, the chief of police, congratulated himself upon having smashed the National Liberation Front and claimed that only two demonstrators had been killed. House and McMaster argue that it is hard to ascertain exactly how many died, but that there were at least 120 excess Algerian deaths throughout the whole of September and October 1961 due to police violence. In this sense, 17 October was the peak of a cumulative wave of repression unleashed against Algerians during autumn 1961. Others estimate the number killed at the demonstration was 200. In terms of colonial violence, this was unique in only one regard – that it took place in the capital of the imperial metropole rather than in the colony. An account of how methods of colonial policing were imported from Algeria to France is provided, many key figures within the Parisian police, including Papon, being veterans of repression in the colonies.

In explaining why the French state was successful in covering up the massacre, the unwillingness of the French Communist Party (PCF) to mobilise seriously in response was undoubtedly one of the most significant reasons. Relations between the National Liberation Front and the PCF were already strained, given the latter’s failure to support Algerian independence. House and McMaster cite the fact that the offices of L’Humanité had their shutters closed while the massacre was taking place outside as “symbolic of the barriers the PCF had placed between itself and the Algerian struggle”.

Protests by students, anticolonial activists and some groups of workers did take place in reaction to the massacre, but none involved more than 1 000 people. House and McMaster contrast this lack of response with the reaction in February 1962 to the deaths of eight communist protesters killed by the police outside Charonne metro station. Rightly they became martyrs, their deaths marked by a general strike and a funeral procession in central Paris attended by 500 000 people. But consequently, for many years afterwards in France, the memories of Charonne were to entirely subsume those of 17 October.

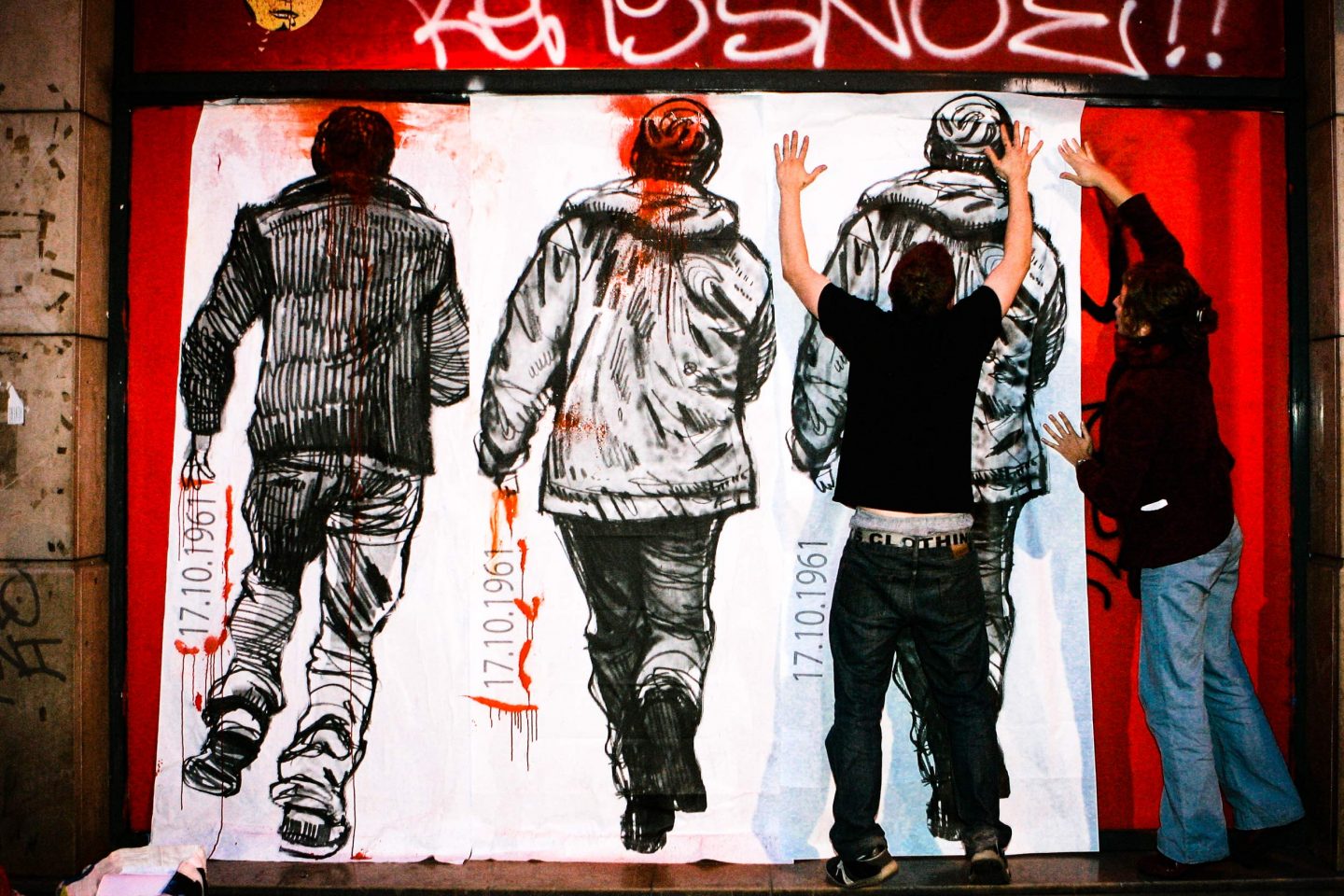

Memories of 17 October have gradually emerged in subsequent years largely due to the work of political and memory activists. In the 1970s and 1980s, groups such as the Arab Workers Movement and anti-racists within the Beur (Arab youth) movement sought to use the memory of 17 October as a symbolic resource against continuing police racism and violence. The 30th anniversary of the massacre in 1991 saw 10 000 people follow the original route of the 1961 march. In 1997, Papon was put on trial for his role in deporting French Jews under the Vichy regime, and his opponents took this opportunity to highlight his subsequent role in the Algerian war. House and McMaster’s book is both an extremely useful contribution towards this still emerging truth, and a damning indictment of colonialism with its attendant racism and violence.