From violence, the gentle harmonies of isicathamiya

Ladysmith is steeped in the bloody history of the South African War, of which there is little account of black lives lost. Yet it is home to the delicate choral sounds of Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

Author:

22 February 2020

In 1986, American songwriter and musician Paul Simon travelled to South Africa. After splitting from Art Garfunkel, with whom he had formed Simon and Garfunkel in 1956, Simon sought to steady his solo career. Despite the international cultural ban because of apartheid, Simon came to collaborate with South African artists for his upcoming Graceland album.

During this time, he met and collaborated with a young Joseph Shabalala. Having left an isicathamiya ensemble called The Highlanders, which his hero Galiyane Hlatshwayo fronted, the slightly built emerging musical genius put together a new ensemble called Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

The group quickly gained prominence. After being played on radio station Ukhozi FM, then known as Radio Zulu, Shabalala got wind of the possibility of a recording contract with Gallo Records. Producer West Nkosi offered the group a deal and Ladysmith Black Mambazo sold more than 40 000 copies of their first album, Amabutho, in 1973.

Thirteen years later, Simon would visit South Africa to collaborate with and compose the iconic 1986 hit Homeless with Shabalala and his troupe of ama’cothoza.

A story of empire and war

In March 1987, the year after Homeless was released, a replica of one of the four 155mm Creusot siege guns that the South African Republic imported in 1897 to man the four forts around Pretoria was unveiled in Ladysmith’s city centre. Dubbed Long Toms, the elongated barrel measured 4.2m and weighed almost 2 500kg.

The plaque says artillery of this nature was used in the siege of Ladysmith, which took place between 2 November 1899 and 28 February 1900. The story these guns tell is one of a war waged on African soil between Boer and English soldiers in the South African War. Nowhere in the recounting of this tale is an account of the black lives that were caught in the crossfire.

-

18 February 2020: The Union Jack, the flag of the Orange Free State and the flag of the old South African Republic which were used in the Apartheid South African flag are depicted on a sign board on the Battlefield Route where the Anglo-Boer wars were fought in Platrand, Ladysmith Kwa-Zulu Natal. -

18 February 2020: A well maintained memorial and gravesite for fallen Boer soldiers in Platrand, Ladysmith Kwa-Zulu Natal. These types of monuments were only erected to commemorate white people who were lost in the wars while all non-whites lie in unmarked graves all over the town.

Shabalala’s quivering vibrato a year earlier on Homeless is a poignant reminder of the displacement and dislocation of black life, which had no voice in the grand stories of English and Afrikaner empire.

Shabalala starts softly:

Emaweni webaba

Silale maweni

Webaba silale maweni

Immediately he tells the story of displacement, of young Zulu men without homes, fast asleep on the cliffs of Ladysmith.

Homeless, homeless

Moonlight sleeping on a midnight lake

Homeless, homeless

Moonlight sleeping on a midnight lake

We are homeless, we are homeless

The moonlight sleeping on a midnight lake

And we are homeless, homeless, homeless

The moonlight sleeping on a midnight lake

-

16 February 2020: Metal sculptures depicting the Grammy Award-winning isicathimaya group Ladysmith Black Mambazo stand at the entrance to Ladysmith in KwaZulu-Natal. -

16 February 2020: The Ladysmith Town Hall is surrounded by replicas of guns from the South African War. -

16 February 2020: A Ladysmith Gazette newspaper poster pays tribute to Ladysmith Black Mambazo founder and lead vocalist Joseph Shabalala. -

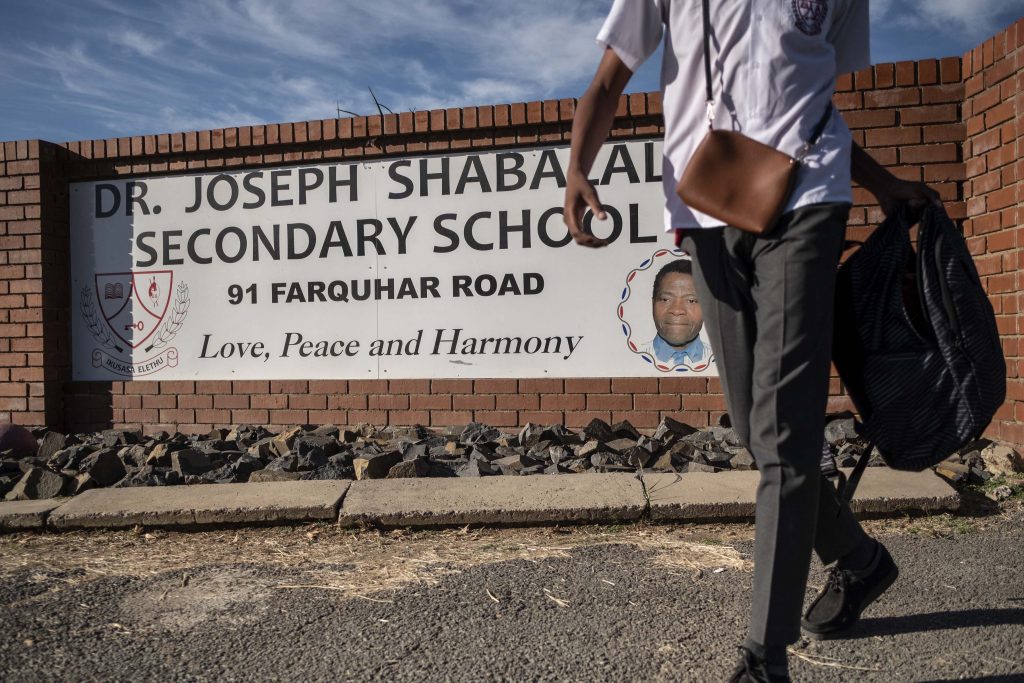

17 February 2020: A schoolboy walks to Joseph Shabalala Secondary School, named after the founder of Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

Violent histories, peaceful melodies

Peacetown is 17km from the city centre. It is an idyllic part of Ladysmith, tucked in valleys through which streams trickle. A 10-minute drive on tarred and gravel roads takes you to Ephayikeni, or Watersmeet. This is where the sound of isicathamiya nestled and was nurtured in the low-lying topography.

As if in spatial resistance to the city centre, which is soaked in the bloody memories of the South African War, Peacetown and Watersmeet are where amacothoza emerge. The isithululu style to which Ladysmith Black Mambazo has given global resonance is sung at a low pitch in the key of E. The sound is reminiscent of lullaby music that, if one is attentive, ebbs and flows as gently as the streams in the valleys of Peacetown. The lyricism is didactic. It is, as the Ladysmith Red Lions group leader James Vilakazi suggests, “the kind of music laden with observations”.

“It is respectful music – music that teaches our society about the dangers of the social ills that abound,” he continues. “Lomculo,” he emphasises, “ufundisa abantwana bethu ukuthi babeclean,” insisting that the music, while not entrenched in respectability politics, is about respect and cleanliness.

Coming from the same place as Shabalala, there are undeniable parallels and forms of symmetry in the sounds of amacothoza of the Ladysmith Red Lions and Ladysmith Black Mambazo. The sounds act as gentle resistance to a history imbued with the erasure of black mortality, creativity and purpose.

In African Stars: Studies in Black South African Performance, Veit Erlmann writes that “certain forms of migrant culture and migrant consciousness such as isicathamiya represent more than a historical phase, more than a passing moment in the inevitable transition of rural cultures toward the formation of urban working-class musical cultures. More specifically, it appears that the development and function of isicathamiya cannot be understood solely in terms of a rural-traditional performance style being used as a mechanism of urban adaptation.”

Isicathamiya, Erlmann writes, “enables people who have been decentred to reconstruct their universe in terms which they can control. By creating multilevel symbols in which to reflect upon the experience of migration, isicathamiya performers are part of the very reconstruction of the migrant’s world.”

Mirroring this sentiment, the Ladysmith Gazette newspaper reported that the name Shabalala chose for Africa’s most successful band was premised on key central themes.

“Ladysmith” the Gazette reports, “was his hometown, Black represented the black oxen that were the strongest on the farm and Mambazo, from the Zulu for word ‘axe’, symbolised the group’s ability to cut down any competition.”

The Ladysmith Red Lions

It is a sweltering hot afternoon. Vilakazi is a tall, composed man who shows no discomfort despite the debilitating heat being the central theme of conversation. He speaks with a mysticism one might expect from a healer deeply connected to other worlds. His speech pattern is slow and methodical, with a hint of musicality every so often.

Like Shabalala, Vilakazi says the melodies and compositions for the Ladysmith Red Lions appear to him in dreams. In fact, before he could fully commit to the Lions, he was en route to becoming isangoma. He had to ask for a kind of ancestral pardon from his elders and ancestors to use his voice in community with others to heal.

The 58-year-old, who looks young and sprightly for his age, joined the Ladysmith Red Lions in 1982 under the vocal stewardship of Mandlenkosi Sibiya. Before that, he was an alto in the choral group Morning Stars.

The Lions were initially 10, but the group now comprises seven singers. The others are Siphamandla Vilakazi, Madoda Ndlovu, Vuma Mazibuko, Sabelo Mazibuko, Bonginkosi Ngwenya and Delani Makhathini.

In performance, the two Vilakazi men centre the troupe. Father and son, James and Siphamandla. When the older Vilakazi gently conducts his troupe of men with soft limbs mirroring fish wading through water, Siphamandla follows with less delicacy but a practiced precision.

“Cothoza mfana,” Vilakazi says every so often as a reminder to his troupe to not only tread lightly in their movements, but also a signifier of the philosophy behind the notion of ukucothoza.

Vilakazi says that to be successful in the broader isicathamiya genre, one needs to really live the ethics behind the music, to tread this indelicate, obscure world with gentleness. For the music to come alive, the musicians must want to find balance in a world filled with the ridges of oppression and exclusion.

“If you hold on to this,” he says with a smile, “your influence and talent will be undeniable. That is why the Ladysmith Red Lions hold a competitive advantage in the local competitions and why we are celebrated across the world.” Their latest tour was to New Orleans in the United States.

-

17 February 2020: Women walking on roads close to the Vilakazi home in Watersmeet. -

17 February 2020: Watersmeet is a 10-minute drive from Ladysmith on tarred and gravel roads.

Hemming the music together

Connected to the sound of the music is its visual component. Vilakazi emphasises the importance of “a pristine look”. “As people who work with churches and people in the community, isicathamiya musicians need to look decent and respectable.”

They rely on an integral part of the isicathamiya community to achieve this – the women who design, hem and create the Red Lion’s uniforms in Peacetown.

The Lions have entrusted their look to two designers, 48-year-old Lindiwe Shabalala and 71-year-old Julia Ndlovu. They are a mother and daughter who have lived in Peacetown all their lives. Their design and sewing work is intermittent and the household has to rely often on Ndlovu’s pension, but they are an upbeat and comical pairing.

Ndlovu’s penchant for making clothes came from a keen interest in the makeup of clothes and curiosity about fabric. She had no formal training, but made small garments for the dolls and teddy bears in the white households in which she used to work as a cleaner. She sharpened her skills and eventually started to design clothes for people.

Lindiwe learnt the craft from her mother. She saved up for a sewing machine and the pair started making clothes for friends and family. Eventually, word got out to Vilakazi and his group and they requested intricately patterned uniforms.

“Whenever the Lions have come to me with an idea about their uniforms, we collaborate on a design and then we figure out how much material we may need and in which pattern and design,” says Lindiwe. “Even this shirt that u’Bab Vilakazi is wearing was made by me,” she says, pointing at him.

“This was an old formal red shirt before, which he was ready to throw away because it was so old. I told him that there was no need to do that and asked him for some material. And now, you see, it’s a totally different creation.”

Their relationship with the Lions is going on five years. But the women were fans of isicathamiya and the Ladysmith Red Lions before that, much like the wives and families of the a capella group.

The women of isicathamiya

Delisile Vilakazi, Gcinile Vilakazi, Nobenguni Vilakazi and Nomfundo Vilakazi are the four matriarchs that tend to the Lions.

They describe themselves collectively as fans, first and foremost. In reality, they ensure that their husbands, brother and sons have food on the road. They are responsible for doing laundry. Those left behind rear the children and, as Vilakazi proudly notes, “imbue the music into the young children’s consciousness”.

“The children you see all over this homestead are almost ready to start singing professionally. Having music in the home all the time has really developed their musical sensibilities,” he boasts.

A similar thing happens in Shabalala’s home. Wives stream in out of the kitchen, readying food for guests who want to offer their condolences. Women play music for the young boys who are milling around the immaculate Shabalala yard, frustrated at not being able to leave the house during this time of grieving.

-

18 February 2020: Joseph Shabalala’s family arriving at his memorial service in Ladysmith. -

18 February 2020: Pastors from the town gathered to pray at the Shabalala home. -

18 February 2020: Ama’cothoza Colenso Abafana Benkokhelo rehearse in the changing room before performing at the memorial service for Ladysmith Black Mambazo founder Joseph Shabalala. -

18 February 2020: The memorial for Joseph Shabalala took place at the Ladysmith Indoor Sports Complex.

Cindy Shabalala, Shabalala’s youngest child and daughter, is preoccupied as she rushes from family meetings, answers calls from dignitaries and the media, and makes sure everyone in the house has had their share of biscuits and juice and curried meat and pap.

At Shabalala’s memorial in Ladysmith, his eldest son Nkosinathi acknowledges this in his eulogy. He speaks about the role his stepmother played in the life and artistry of his father and asks, “When will Mambazo be led by a woman?”

The venue falls into uncomfortable silence. He repeats the question. “When will Mambazo be led by a woman?” He looks directly at his sister. They share a knowing look.

Diamonds in soles

Serendipitously, after leaving Vilakazi’s home in Peacetown, a 15-year-old boy in a white vest and cropped denim shorts blares Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s Diamonds on the Sole of Her Shoes from his portable speaker.

It is a gentle reminder of Shabalala’s elaborate life. “I am playing uBab’ Shabalala’s music here today because even though he has left us, he is still here with us all around Watersmeet,” Nhlaka Kunene tells us.

In the days to follow, this image of a boy playing this song takes on new meaning. It is a call to remember the women in isicathamiya. It is a reminder of gentle music that humanised black life in the village. It is a reminder that despite Ladysmith’s turbulent and violent past, the orators of our stories will transcend space and time because they have diamonds in the soles of their shoes.