Hope and Beauty, a survival story

Beauty Ndlovu turned to sex work when she had nothing left to sell to support her children. And then came Hope, a special little girl who is her mother’s hope and joy.

Author:

9 December 2020

Beauty Ndlovu has learned to shrug off the stares from inquisitive eyes that she and her youngest daughter Hope attract as they walk along the streets of their Johannesburg suburb, Yeoville.

But for eight-year-old Hope, it is not as easy.

“You know, kids are naughty, and they tease each other sometimes,” said Beauty, 42, sitting on the steps leading to the house where the two of them live in a rented room in one of Johannesburg’s oldest suburbs, on the eastern side of the city.

“When we go to the streets, the kids who don’t know her, they will all say, ‘This child does not have a hand,’ and she will tell me, ‘You see, these kids are talking about me.’ She will be very angry with them.”

Hope was born without a right hand. Beauty considers it a miracle that Hope survived at all, because her twin was born severely deformed and died shortly after birth.

Beauty’s life was tough even before this loss. She came to Johannesburg in 1996 from Plumstead in Zimbabwe, aged 18, and already a mother, to look for work. She first worked at a pizza shop and then as a domestic worker until her employer died. This left her unemployed and struggling for several years. She also contracted HIV at some point, but does not know when. Battling to feed her two eldest children after falling ill with tuberculosis and being abandoned by her husband saw her doing sex work for a time.

Related article:

These challenges have taught her resilience, a quality she hopes to instil in her daughter to enable her to live as normal a life as possible. It’s a desire born from her fierce protectiveness of Hope. “What I don’t want with her, is if people see her like this, they go, ‘Eish, this child.’ That is what I don’t like. I get angry, because they have to take her as a normal child,” Beauty said.

“I don’t want anyone to feel sorry for her. If you come and ask me nicely what happened, I’ll tell you. I don’t have a problem. She was born like this, it is a normal disability. I am not shy with her, I go everywhere with her.”

Drawing and playdough

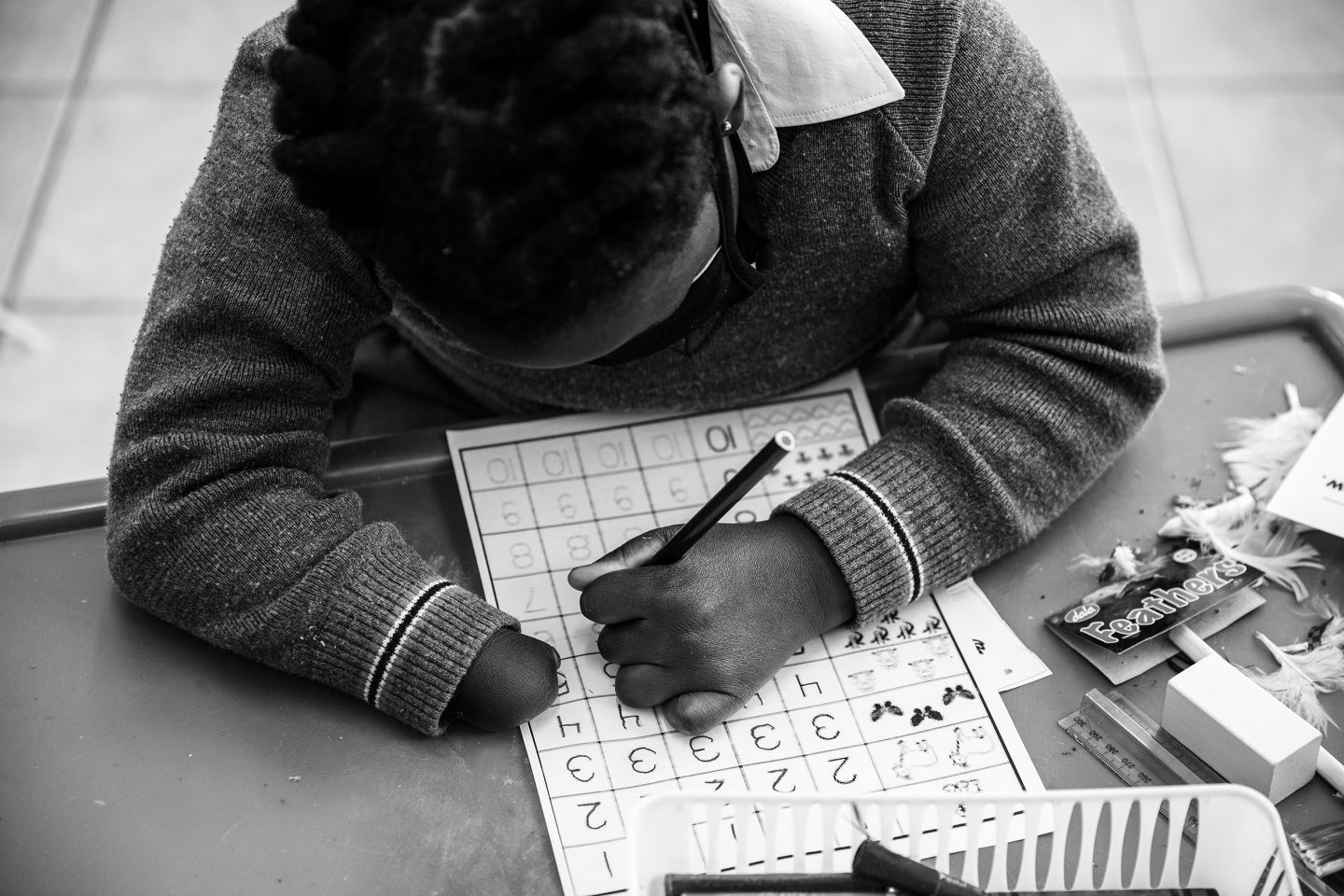

Hope has a learning and intellectual disability as well. One of Beauty’s proudest moments was when her daughter learned to write her name and count up to 10.

Hope doesn’t speak more than a few words at a time, but has come to love going to her school, Forest Town School, in the leafy suburb with the same name. “I love learning with my friends and Teacher Brenda,” she said. “I like playing and making something with playdough.”

Hope’s teacher, Brenda Ben-David, has a soft spot for her. Two of Hope’s favourite school activities are drawing and colouring in between the lines, something other children in the class struggle with, according to Ben-David. Drawing herself on a sheet of paper, Hope is almost oblivious to what’s so obvious for others, and draws herself with two hands and 10 fingers.

While Hope enjoys creative activities, she needs encouragement from Ben-David when it comes to counting exercises. Counting on one hand, Hope struggled and kept repeating the wrong numbers, but with her teacher’s encouragement and the promise of a packet of chips later, she successfully completed the exercise.

Related article:

All the activities in Ben-David’s class are geared to teaching the children to become more independent. But besides that, Hope is conscious of the needs of others in the class and looks out for them, for example when a bag or dustbin is in the way of her favourite teacher, who has a visual impairment.

“What I have taught her that’s quite sweet, is in the morning she makes me coffee. She’s not allowed to pour hot water, but she’s allowed to do everything else. It’s nice to see because this is what I was talking about, becoming independent,” said Ben-David, who has been teaching at the school for 28 years. “If I need to send somebody to the office to collect something, she’s the only one in the class who can go.

“She’s my saviour sometimes. Her desk is right next to mine and sometimes I can’t find something. I’d say, ‘Hope, where did I put my register?’ She knows the register is orange and she’ll go and look for it. Sometimes I drop something and I can’t see it, or I’m going to fall over something. She’ll say ‘Be careful!’ or she’ll move the dustbin,” Ben-David said.

“She’s just a nice child. She always says thank you, and if you’ve got something nice on, she says to you, ‘You look pretty.’ She has that social awareness to compliment someone. It’s really rare,” Ben-David explained.

“She’s always aware if you’re sad, or if another child is sad. She’ll come and tell you, ‘Teacher Brenda, so-and-so is crying.’ You can ask many of the children, ‘Why are you sad?’ but they can’t tell you. They can’t express emotion, but she can.”

Places of support

In the nearly two years that Hope has been going to Forest Town School, she has made more progress than her mother ever thought possible. In their room at home, with its peeling walls, Beauty has educational posters stuck on the walls showing shapes, colours and farm animals.

When Hope was born, Beauty feared that she wouldn’t be able to walk or talk. But Hope exceeded all her mother’s expectations. She’s able to help with laundry and hanging washing on the line outside, and makes her bed every morning. The only thing she needs help with when getting dressed is tying her shoelaces.

“When she was born, I was very worried that she won’t be able to do anything. Because her growth was also slow, I worried if she was going to be like a normal person and if she was going to be able to do all the things she does now,” Beauty said.

The one place where Beauty feels Hope is never stared at is the Jerusalema Apostolic Church in Yeoville, where they attend sermons in a small classroom every Sunday. “They don’t treat her as a child with disability. They love her so much and we feel at home when we are at that church,” she said.

Dressed in her white uniform on a recent Sunday, Hope sat still for hours during the service and sang along with the congregation. She also took part in a prayer, while Beauty was later blessed by congregants.

It was another religious institution, the Sister Mura Foundation in Yeoville, as well as a local ward councillor, that helped Beauty get Hope into the school that could provide her with the appropriate education. “I didn’t know what to do with her. If it wasn’t for the Sister Mura Foundation, maybe today she would still be at home,” Beauty said.

The foundation has played a pivotal role in Beauty’s life in other ways since she first went there for emotional and psychological support more than a decade ago. It is here that she first learned how to do beadwork, which provides her with her main source of income these days. Hope loves helping her mother with the beadwork, working very fast using her hand and mouth.

Ill and abandoned

It was in 2008, while living with her then husband in Diepsloot township, north of Johannesburg, that Beauty got sick, an event that would change the trajectory of her life. “I went to Helen Joseph Hospital and I had an operation. They said it was abdominal TB [tuberculosis]. I had to get treatment for nine months, but they didn’t say anything about HIV. My husband said, ‘I can’t stay with someone who is sick.’ That is when he ran away and left me.”

Beauty was unemployed when her husband left her. Alone and sick, she went to live with her sister in her flat in Hillbrow, but within months her sister, who also had HIV and TB, died. They had to use the deposit for the flat to return her sister’s body to Zimbabwe for burial. Beauty had to find new accommodation, and money soon ran out.

“I started selling everything I had, because I had two kids. They needed to go to school, to eat, to do everything, and I needed to pay rent. After three months, I even sold my clothes,” Beauty said.

“When the things were finished, I didn’t have anything. There were girls staying [at the same house] who were working at a restaurant. They used to go at night and come back in the morning. I cooked for them or did their washing to make a living. One came to me and said, ‘You know what, we go to Orange Grove, we do prostitution. You are a mother, you are struggling, we think you should go and try your luck,’” Beauty said. “That is how I started.”

Beauty was apprehensive about starting sex work while still ill with TB. The women who had encouraged her to take up sex work told her about an organisation in Yeoville that assisted migrant women and sex workers where she could get help. “I went there, they did a test, they said the results will come in two weeks’ time, and in two weeks’ time they said I am HIV-positive,” Beauty said.

Despite the diagnosis, Beauty continued working. Often clients would offer to pay more to not use a condom. That is how she became pregnant with the twins. “I needed that money. We didn’t use a condom because he had money. And unfortunately, that time I got pregnant,” she said.

‘Four months and two weeks’

She didn’t immediately realise it. Her HIV medication affected her body in ways she wasn’t aware of. “Only my breasts were getting big. I kept going back to the organisation, telling them. They said, ‘These tablets, they change your shape.’

“When I was four months and two weeks, the doctor said to me, ‘I think you are pregnant.’ I said, ‘I am not pregnant.’ I went to do the sonar. The sonar showed I was four months and two weeks,” she said.

“I was shocked. I wanted to do abortion because [of] the life I was living. Having another baby – I don’t know the father, I am struggling – I saw that it would be difficult.”

Social workers talked her out of having an abortion. “They said, ‘Don’t do this. You don’t know why God gave you these children.’ After that, they gave me nevirapine to protect the children.”

Related article:

It wasn’t an easy pregnancy, and it was even more difficult for Beauty when she lost one of the twins.

“I decided, let me take this name, Hope. Because I hope that she will live and nothing bad will happen to her. I hope for a bright future for her. And maybe she is here to bring a bright future in our lives.”

This project was undertaken in partnership with Wits University’s African Centre for Migration and Society and the International Organization for Migration, with funding from the Irish Embassy. This story is part of The Endless Journey – a series of stories about migrants with disabilities.