Long Read | Regarding Lady Skollie’s ‘Bound’

Lady Skollie’s latest exhibition adds to the thinking of Patric Tariq Mellet, Gabeba Baderoon and Pumla Dineo Gqola on slave history and its sexual violence, and how it remade our world.

Author:

18 December 2020

When poet and scholar Gabeba Baderoon was a graduate assistant at the University of Cape Town in 1988, there was a conference on Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness. As she looked at the programme, her gaze paused, fixing its attention on the cover image. It was something “meant to be glanced at briefly before one went into the substance of the programme”. But she looked intently, instead, and saw that it was a “picturesque image of an enslaved figure”, caught in a “play of visibility and invisibility”.

As she recalls this memory in her book Regarding Muslims: From Slavery to Postapartheid – a work that creatively thinks seriously about the image of Muslims in popular culture – she writes about how “such figures elude recognition even when they are in direct view”. She names this “ambiguous visibility”. This term speaks to ways of seeing that have been shaped by oppressive power structures so normalised that we cannot even truly see what we are looking at.

The artist Lady Skollie’s recent exhibition at the Everard Read Gallery in Cape Town works in this mode of visibility – with skill and dexterity and on many frequencies. Her art is defined by a complex meeting point of history, popular culture, indigeneity, violence, sex and sexuality. It asks us to look again and again and again…

Lady Skollie appears on a Zoom call in a room walled by a mirror. It reflects both our images back to the computer screens. When we first met, the artist had just moved to Johannesburg from Cape Town, determined and tenacious. Now, she is the winner of the prestigious FNB Art Prize. Her statements about her work and the art world are accented with laughter, punctuated by frequent jokes and self-reflexive winks in word form.

Her urgent art – “hard, fast and now”, as she describes it – has a deep historical consciousness. Bound, which follows last year’s Good and Evil, is inspired by writings of women in captivity across time. It runs a red ribbon into our slave past, connecting it to the ways we are bound in the present. As she told Sandiso Ngubeni, the work is “about liberation and trying to be free because even now as women in modern-day South Africa, we are living in captivity. We can’t move freely, we can’t go wherever we want to go. So, it is about trying to find liberation in a place where captivity is bred into us.”

Her words are chillingly accurate when thinking about the ways that sexual violence was central to slavery. It is a reality, obscured by the idea of slavery at the Cape as “mild” or “benign”, as Baderoon points out. What we appear to acknowledge, in national discourse, is not seen. It is politically pixelated.

-

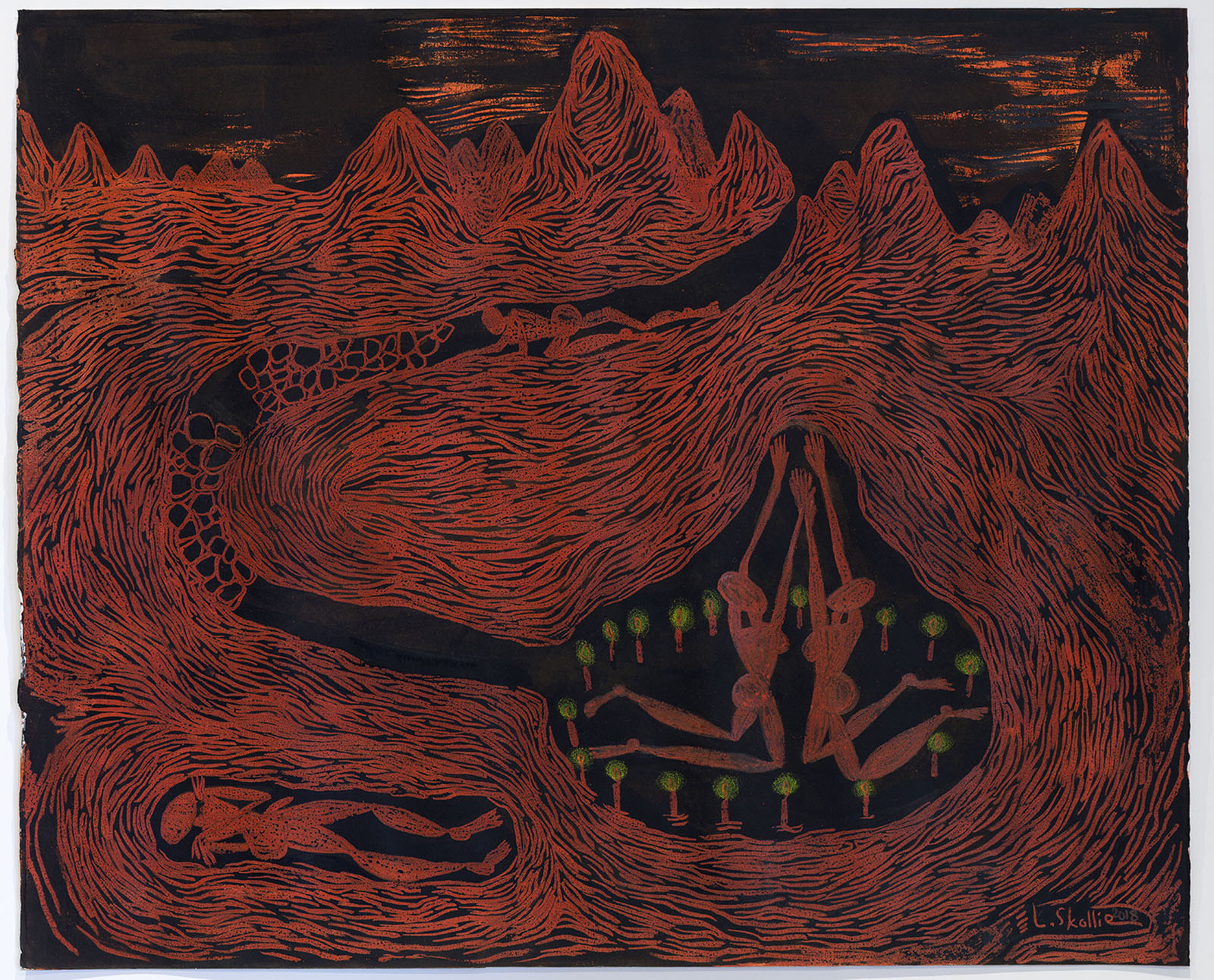

Undated: Drie Susters. Lady Skollie’s new work uses a lot of red tones and is darker than her previous exhibition, Good and Evil. (Image courtesy of the artist) -

Undated: 1 in 4, 1 in 3, 1 in 2, 1 in 1, All of Us points to the makings of rape and rape culture in South Africa, linking it to slavery in the Cape. (Image courtesy of the artist)

The makings of the world

For author and scholar Pumla Dineo Gqola, seeing the way slavery remade the world is critical. As we speak over Zoom, she explains how sexual violence defined slavery – the particular form of slavery that gave rise to capitalism. It created the modern world on violent terms.

Gqola’s intellectual project, she reflects, is not only about the histories and workings of sexual violence. “It’s also about saying, ‘How do we think about slavery as foundational in how we think about the rape culture today’… If rape is a language [that remakes the world in slavery], what does language do?” she asks.

This is not a metaphor. It is about how sexual violence creates slavery and the world, sharply and directly forming ideas and categories of race and gender (in their intersections), stereotyping ideas of violent sexualities and commerce – shaping our language, constructions, institutions and laws. These are “constructions used to manage anxiety around white masculinity”, producing the violent logic of who is considered “violatable and not”, “enslaved and enslavable” that, in many ways, remains with us today.

As Gqola speaks, she turns her sentences in on themselves, and in multiple directions, before moving forward. She travels through thought, her words a guide on intellectual pathways. “We continue to think about slavery as though it’s a moment that popularises rape … or we think about rape as one of the things inside slavery, but actually there is no slavery without rape.”

“We can’t think about this crisis without thinking about its roots in slavery,” she says, explaining how “slavery and colonialism [are] projects of sexual violence” and not “violent systems that used sexual violence … even as we recognise that rape precedes capitalism in the world, because patriarchy is older”.

“When we say that rape precedes and predates colonialism we are factually correct, but what we don’t understand is the way slavery changes how rape works, and we live in the aftermath. It amplifies the importance of rape, it creates a world in which rape is necessary, is the authorising language, is at the centre of every system, [which] creates the idea of the factory.”

Related article:

The female fear factory is the core of her book on rape – thinking about the “theatrical” and “spectacular” way fear is manufactured, and how it relies on “frequent repetition of performance until the performance becomes invisible”. “When we see and hear something over and over again,” she writes, “we stop seeing and hearing it.” The spectacular violence of the everyday becomes normal, and fear becomes embodied, reminding vulnerable people – particularly women, queer men, non-binary and trans folk – that their “bodies are not entirely theirs” and “curtailing movement in a physical and psychological fear”. “South Africa’s public culture is infused with this phenomenon,” Gqola writes.

We are “apparently free”, Lady Skollie says in a television interview promoting the exhibition. “Democracy tells us we are free, but we live these very bound, constricted lives.”

Bound by the architecture in us

The Everard Read Gallery is next to the site that used to be the Breakwater Prison. It’s a haunting echo that makes the work, if not site specific, then specific in its site. The way that the material structure of the present is haunted by the brutality of the past is enabled by the way the city was built – and it is everywhere.

“My gallery is actually the old harbour master’s house,” Lady Skollie says, “and then the harbour master’s house was right next to Breakwater Prison.” The prison is now a lodge.

“We don’t even realise how evil those places are or what those places were used for,” Lady Skollie reflects, “and now we just do our graduate business school there and go on honeymoon … but actually it was a prison … the whole of Waterkant is pretty much a prison.”

Lady Skollie’s connection to this reality is deeply personal. “I’m a direct descendant of people who were brought here as convict slaves,” she says. “This [show] is as much about the bondage as it is about the many places in Cape Town that have built-in evil. We pass and interact with these places every day without even realising it.”

Related article:

About forgetting and “disremembering”, she says: “I think that in Cape Town often we become very desensitised to spaces and how they architecturally affect us.” When she googled the Breakwater jail treadmill – a violent device of slavery and commerce – “it came up under myths, legends and old folk tales”.

In an interview with Patric Tariq Mellet about his recently published book, The Lie of 1652, he points out: “This entire economy of ours, the colonial economy, in the Cape in particular, the infrastructure was built by people who were enslaved … The building of roads, the building of cities and towns, clearing farms for cultivation, running those farms. Even the earliest animal husbandry and pest control, all of this. The Europeans required indigenous knowledge for this. However, the treatment of the people that they enslaved was cruelty in the most depraved way that you can think. From the manipulation of people’s reproductivity and ripping people who are in relationships apart from each other, and so on.”

He names places like Cape Town “slave towns and not simply segregated towns because they were a progression on the slave lodge and on the system of mind control … So you begin to see again, this thing of the control of the mind, the control of the body and the control of the social group woven into South African history from the earliest times.”

Baderoon, Gqola, Mellet and Lady Skollie each point to continuities, mutations, traces and echoes of the past. Mellet says: “Apartheid does not just suddenly magically appear in 1948, apartheid was simply the finessing of a system that was already in place.”

Ambiguous visibility

What is visible and what we see is political, philosopher Jacques Rancière says about aesthetics. It is a system that defines and delimits “spaces and times … the visible and the invisible … speech and noise”. It “simultaneously determines the place and the stakes of politics as a form of experience. Politics revolves around what is seen and what can be said about it, around who has the ability to see and the talent to speak.”

This is not solely a matter of who counts, of who can be seen and heard. It is also a matter of which historical events and the forces they create can be given due weight. And history continues to shape the present, forming the powerful forces that shape cities and economies, all the way down to the subtleties of intimate relations. As the American academic Ian Baucom writes, “Time does not pass or progress, it accumulates, even in the work of forgetting or ending, even in the immense labour it takes to surrender what-has-been, or to make reparation on it, or to address its ill effects.”

With this in mind, Baderoon’s viewing of the picturesque figure of the enslaved person on the programme reappears, and how she speaks about ways of seeing that make “the violence of slavery impossible to recall”.

“Baderoon is really such an incredible theorist of and on visibility,” Gqola says. “Her work is so important for thinking about – in our context and beyond – how we come to see what we see.” This is “not just in terms of ways of seeing and the histories of how certain things become visible and specific ways of learning to interpret what we see.” It is also about recognising that part of remembering requires acknowledging that “history is not just about tracing origins. It’s … about saying all of the messy power stuff that was embedded in the originary moments of seeing in this way, remains and is retained as this way of seeing travels across time”. What is visible is not all that is there. It is about “being able to remember and take seriously the traces of power” that show “us how visibility is constructed and normalised”.

Visibility, here, relies on obscuring. And here is where its ambiguity emerges. “It’s not just that we are socialised into not seeing,” Gqola says, “we are also socialised into limiting ways of how we see.”

Seeing through the obfuscation of accumulated oppression is, then, always in process – a perpetual commitment. Like identity, we never arrive and have completely seen, she says. As Gqola riffs on her thoughts, like a jazz musician, she reflects that “part of the obscuring [of this ambiguous visibility] is that it pretends that the moment of recognition of the trace [of the past] is the seeing”. So we (mistakenly) stop there. “But Baderoon reminds us that that is not the moment of recognition. That is the deceptive moment.” This is “ambiguous visibility”.

Remembering slavery, then, is not only a statement, plaque or event – the kinds of things that “even when it says [slavery] is a foundational moment, it makes it a moment. It makes it impossible to see the ways [that] slavery is a language.” These kinds of acts of memory, for Gqola, allow “us to think slavery is there, was there, it’s complete, it’s done, that’s the site [where slavery existed]”.

There is an immobility to this kind of memory. “One of the games that disremembering requires is that we keep thinking we have arrived,” she says, that we have seen all there is.

Continuous looking

Lady Skollie’s work invites continuous looking. It is brightly coloured, gold-leafed, beautiful and often large scale. Her new work uses much red and is darker. She draws us in and up close, revealing what she calls “the ugliness” and “the rot”. Everything is never as it appears.

While the work in Bound is not figurative, there are people everywhere. The bodies of Black people are always in mind, even when not in frame. They are present when she paints offerblomme [sacrificial flowers] in hues of pink and orange, an image of “one ear at the bottom of Table Bay” in memory of Susanna “Een Oor [One Ear]” Van Bengale – an enslaved women whose ear was burnt off. The ocean is a swirling purple and black current. And they are present when she paints indigenous plants with the caption, 1 in 4, 1 in 3, 1 in 2, 1 in 1, All of Us, pointing to the makings of rape and rape culture and its pervasiveness, and to the activist words and work of feminists in South Africa.

Bodies are most visibly clear in works such as Burning Bush: Avert your Gaze, the Truth is Ugly and Bright. The title of the work and its biblical roots speak of revelations set alight. Here the foundational realities of sexual violence in South Africa, and the way it is regarded, are rendered in a tree that, close up, seems to bear papayas as fruit, and in the sapphic shape of the flames. The figures look away.

There are so many dense and rich meanings she encodes into her work in layers of paint and gold leaf. While beautiful, her work does not engage in the picturesque or in a visual language that indulges itself. She refuses this. This work is no alibi for averting one’s gaze.

Looking at some of the works in Bound, it is as if the artist takes a camera lens and zooms into the images from Good and Evil. In a previous image figures drinking from green bottles are surrounded by blue ocean with a ship appearing on the horizon. A rainbow hovers above. Now, it becomes solely the ship, the first Dutch East India Company ship arriving at the Cape. The title? Impending Doom Approaching, or, and as she captioned it on social media, Terror Approaching.

Terror, doom and violence are palpable today with a clear apprehension both that, as Mellet’s title references, history did not start in 1652, and the inane idea of an instant “rainbow nation” miraculously arriving in 1994 could not undo the crushing weight of history.

Regarding Bound

Lady Skollie is thinking about survival and memory, as we speak. For descendants of enslaved people, who were raced as “coloured” after being freed from slavery, she is thinking about how forgetting becomes “a coping mechanism”, as romantic ideas replace a violent reality.

“Sometimes the pain is so deep that if you feel it, you might explode and literally die,” she says. “So, I think that it’s not that coloured people want to turn away from the truth necessarily, it’s just that the truth is so evil that if you were to turn towards it as a collective, we might literally combust.”

“One of the things that I just love about Skollie, when we’re talking about visibility,” Gqola says, “[is that] she is a visual artist who plays around [with what is visible]. You know what you can see, but you also don’t know what you can see … And, of course, there are other artists who do this kind of thing in different directions.”

“She’s giving you something,” Gqola says, reflecting on the artist’s paintings, “but she’s also very consciously reminding you that you need to be asking questions.”

“Bound”, as a word and in Lady Skollie’s exhibition, has many meanings: territorial limits, leaping towards something, being enclosed, destined towards, constrained, and compelled. Captivity is not only about the visible constraints, the physical containment, the prison bars – it is also deeply part of the structure of our world, infusing it. “Regarding”, as Baderoon and Gqola point out, also has multiple meanings: to look, refer to, contemplate, consider, respect, take seriously, reference, study, keep in mind.

Lady Skollie never tells you what to see or to regard, but in the urgency of her work, she presents the remaking of the world in layers, clearly pointing to its violence in a series of paintings that ask you, instead, what it means to look, to see, to regard.