Long Read | Sinclair Beiles and the Beat Generation

The enduring relationship between the ‘wandering poet’ from South Africa and peers such as William S Burroughs is not widely known outside literary circles.

Author:

2 March 2021

Poetry is in the streets

– Wall poster, Paris, May 1968 uprising

Down the dark streets, the houses looked the same

I walked round and round, they nailed me to a tree

Trying to find a clue, trying to find a way to get out!

– Interzone by Joy Division, 1979

The 1950s were a tumultuous time for an Australian criminal and con artist called William Lindsay Pearson. An array of jewels was stolen from Brenthurst, the Johannesburg estate of the Oppenheimer family, founders of the Anglo American mining giant, in 1955. This treasure was, ultimately, derived from political connections to the apartheid state and the exploitation of Black workers.

Pearson’s exact role in the theft is unclear. But he had enough insider information to brazenly approach the Oppenheimers’ insurance agency, asking for a reward in exchange for revealing where the jewels were hidden. According to Famous South African Crimes by Rob Marsh, he approached the insurers with the memorable opening line: “Gentlemen, I’ve been a swindler and confidence trickster all my life, and I’ve no intention of changing now.”

After he was deported from South Africa, narrowly missing a jail sentence, he washed up on the shores of Tangier in Morocco. A “free city” governed by several different countries, Tangier was a place of smuggling and excess. The “capital of treason”, as French writer Jean Genet called it, the city was home to outlaws fleeing extradition, wealthy hedonists and those who lived on the edges of polite society.

Pearson decided to rob a bank in the middle of the city, choosing to do it on a busy Saturday. He was quickly arrested. Intrigued by the story, the Johannesburg newspaper Sunday Express asked a young writer named Sinclair Beiles to interview Pearson in jail.

Born in Uganda, Beiles had moved to Johannesburg as a six-year-old. He would develop a love of poetry, in particular the radical tradition of French poetry. In the late 19th and early 20th century, in the aftermath of the violent suppression of the 1871 Paris Commune, writers such as Arthur Rimbaud had grandiosely called for poetry to be used as a tool for “reinventing society according to the laws of the unconscious, replacing reason with desire”. This idea – of literature as a revolution of the mind – defied the ethics and social order of bourgeois capitalism.

Related article:

As co-editors Gary Cummiskey and Eva Kowalska write in their fascinating collection of essays about the poet, Who Was Sinclair Beiles?, he was especially influenced by the Dadaist and surrealist movements, which prioritised dream, adventure and risk.

While still a student at the University of the Witwatersrand, Beiles had engaged in a scandalous affair with a married woman. He left the country in disgrace and spent the 1950s living and working in Europe and North Africa, while meeting many of the bohemian luminaries of his time.

Enter the beatniks

After reporting on the ill-fated Pearson, he went to interview the denizens of a Tangier restaurant called Dutch Tony’s, run by a man who used to work for the infamous American mobster, Dutch Schultz. Inside, he would meet another disreputable American, William S Burroughs. A hardcore drug addict and the black sheep of a prominent St Louis family, Burroughs was at that stage a marginal figure, known only for an obscure pulp novel called Junkie.

He had spent the previous decade in a permanent midnight of extreme addiction that included accidentally shooting and killing his wife Joan Vollmer, in what was described as a “William Tell” game gone wrong. In Tangier, he drank and caroused with other disreputable figures. Established expatriates like the writer Paul Bowles wanted nothing to do with this seedy figure.

But within a decade, Burroughs, along with his friends Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, would be cultural icons. The leading figures in what is now called the Beat Generation, they collectively produced three era-defining works: Ginsberg’s poem Howl (1956), Kerouac’s novel On the Road (1957) and Burrough’s experimental novel Naked Lunch (1959), in which Tangier was reimagined as a feverish dystopia called Interzone.

Related article:

Condemned as obscene and depraved by many established literary gatekeepers, the term beatnik – derived from Sputnik, the first Soviet space satellite launched in 1957 – was initially used by the media to suggest that this literary movement was subversive and communist inspired.

However, the men and women of the Beat Generation’s libertine approach towards sexual and drug experimentation, and their interests in Zen mysticism and anarchism, was equally oppositional to the conservative official culture of the Soviet Union.

Beat writing, from both the established authors and dozens of lesser-known figures, landed like bombs on staid, conformist post-war society. In Liverpool, England, an art student and Kerouac enthusiast named John Lennon named his new band The Beatles in their honour.

Radical inspiration

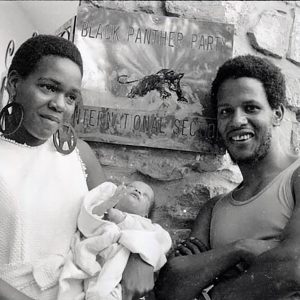

The Beat Generation’s anti-establishment writings and lifestyles became key strands of the DNA of 1960s radical culture. This went beyond their obvious influence on the psychedelic culture of the hippies. According to music historian Peter Doggett, as Huey Newton, one of the founders of the Black Panther Party, planned a new movement for black emancipation, “his hi-fi blared out Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited. From LeRoi Jones’ apprenticeship amidst the Greenwich Village beatniks to the Ginsberg-inspired surrealism of Dylan’s electric fantasy: a revolution in words fuelled a revolution in deeds”.

This discontent and rejection of consumer capitalism and social repression peaked in 1968, when youth-led strikes and radical movements in France, Yugoslavia, the United States and Latin America took to the streets to challenge the state.

As shown in the acclaimed new film Judas and the Black Messiah, which explores the FBI’s involvement in the assassination of Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton, many of these dreams would crumble in the wake of state repression and internal conflicts.

Related article:

Beat writers would not unanimously support the radical culture. While Ginsberg was an outspoken socialist and opponent of the Vietnam War, Kerouac increasingly became a conservative Catholic before his death from chronic alcoholism in 1969.

An ambiguous sense of defeat and exhaustion was the underside of the Beat movement’s optimistic hopes for personal and social liberation. It even started as a scene that was halfway between bohemianism and the criminal underworld.

When they first met in 1940s New York, Kerouac, Ginsberg, Burroughs and the people in their social circles were, according to biographer James Campbell, as familiar with mental hospitals and prisons as they were with philosophy and poetry. In the case of Burroughs and Ginsberg, much of this personal instability was caused by being gay men in a society where homosexuality was still criminalised.

Sexism and prejudice

Yet despite their personal radicalism, the Beats also reflected some of the prejudices and casual sexism of the dominant society. Until fairly recently, the key role of women as writers and artists was often sidelined in research on the movement.

This also extends to the ways in which the disturbing behaviour of male writers has often been legitimised, even glamourised, particularly with regards to Burroughs and Vollmer. The two shared a deep bond, referring to each other as “psychic soulmates”, and married despite Burroughs being openly gay. Both pursued other relationships and the marriage quickly descended into a downward spiral owing to their respective addictions to opioids and amphetamines.

Their union ended tragically in Mexico City in 1951 when, after a day of binge drinking, he offered to do a magic trick that involved shooting a glass off Vollmer’s head, who readily agreed to the “routine”. Burroughs fired, missed and immediately killed her.

According to Burroughs and many biographers, the guilt from this violent act forced him to become a writer. In some cases, there is even an implicit and patriarchal attempt to rationalise the shooting, as if Vollmer – a key Beat figure in her own right – was a martyr who died so that great literature could be produced. This romanticised depiction serves to underplay the severity of Burroughs’ reckless actions. It reflects more broadly how the violent actions of male “geniuses” are often tolerated because of their cultural influence.

In Burroughs’ case, the cynical, nihilistic vision of Naked Lunch – which shows a world of absolute cynicism and utter paranoia – warped art long after the utopian hopes of the 1960s receded. The dark poetry of punk musicians like Lou Reed and Patti Smith, novelists JG Ballard and William Gibson, and film directors such as David Cronenberg all reflected his influence. Iconic United Kingdom post-punk band Joy Division borrowed the term Interzone to describe the bleak urban alienation of post-industrial Manchester.

While the emotional landscape of Kerouac’s On the Road seems to belong to an earlier, more optimistic era, Naked Lunch anticipates the predatory hyper-capitalism of today. Burroughs shows a world in which everything – and everyone – is for sale, offering a grotesque vision of a society that revolves exclusively around merchandise, illicit commodities and sinister, authoritarian control.

Returning to Paris

Beiles had no idea that his initial meeting with Burroughs in Tangier would come to define his own life and work – and not necessarily for the better. Within a few years, he would also meet Ginsberg and Kerouac, before returning to Paris.

He worked there as an editor and writer for Maurice Girodias’ Olympia Press, one of the most idiosyncratic book publishers. Girodias specialised in a strange combination of erotica and high-brow fiction, which included publishing works by major literary figures Samuel Beckett and Vladimir Nabokov.

Related article:

Paris also attracted Burroughs, Ginsberg and poet Gregory Corso, who stayed in run-down lodgings that soon became known as “the Beat Hotel”. Owned by an incredibly tolerant woman named Madame Rachou, the hotel became the site of wild experiments with writing, art and drug-inspired magical rituals.

Girodias purchased an early version of Naked Lunch, but finding that the manuscript was unreadable, Beiles was sent to the Beat Hotel to acquire a more legible version. In a cramped room full of greasy candles, Burroughs presented him with the final draft of what would soon become an era-defining text. Bizarrely, he also seemed to think that he was a psychiatrist and that Beiles was a patient scheduled for a session.

Despite this bad omen, Beiles moved into the Beat Hotel, finding its disordered atmosphere conducive to his work. While staying here, he collaborated on the book Minutes to Go with Burroughs, Corso and English painter Brion Gysin. This book used an experimental “cut-up” technique, in which poems were created by cutting up existing texts and reassembling them to create new meanings.

The technique would later be used by musicians like the Rolling Stones and David Bowie. But while its origin is often attributed to Burroughs and Gysin exclusively, Beiles deserves at least some credit for playing a key role in these early experiments.

At this point, Beiles could have been poised to use his connection with the Beats to establish his name as a poet. However, he began to be plagued by severe bipolar disorder, and manic spells would end with sectioning inside mental asylums. He started to carry a shopping bag of tranquillisers with him, becoming increasingly difficult and unreliable with his friends and collaborators.

But Beiles never stopped writing and he won the 1969 Ingrid Jonker Prize for his evocatively titled collection, Ashes of Experience. But despite his prolific output, he refused to edit his work and often let it be published in tiny print runs of fewer than 20 copies. This lack of curation meant that his work was of wildly uneven quality, ranging from lucid beauty to garbled nonsense.

The Yeoville years

Beiles returned to South Africa in the late 1970s after his – apparently highly domineering – mother became gravely ill. More involved with fighting personal demons than anti-apartheid struggles, his interviews and writings nevertheless show that he was fundamentally opposed to the racist, tyrannical state. From his perspective, his bohemian and restless lifestyle was, in its own way, a form of rebellion against the insular and paranoid culture of white South Africa.

In Johannesburg, he would become part of the artistic and political hub of Yeoville and an eccentric habitué of local bars and restaurants. Newspapers would send reporters to speak to the “wandering poet” about Burroughs and Paris. While he spoke highly of his former collaborator, with whom he still corresponded through letters, he would launch into virulent attacks on Kerouac and Ginsberg.

This verbal hostility came from a place of mental anguish, but it also speaks to a more specific resentment. All poets and writers dream of having an impact on culture in the most profound ways, and producing work that is discussed and celebrated long after they die. Beiles was in the position of knowing people who achieved this status – even if at great personal cost – while never finding it himself.

Since his death in 2000, his name has appeared in the indexes of books about the Beat Generation, but always as a side character and never as an artist in his own right.

But perhaps eternal literary celebrity isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Before his death in 1997, Burroughs had become almost a parody of himself. Surrounded by celebrity sycophants – like Bono – and drugs, he produced often repetitive subpar work, even appearing in a Nike advert.

Capitalist kitsch

I visited North Beach in San Francisco in 2014. The home of the legendary City Lights bookstore, this neighbourhood has become the spiritual mecca for tourists following the Beats. In one of the stores in the area, there was a plethora of beatnik merchandise, including a T-shirt of Burroughs waving a gun. In this image, all the dark complexity of the Beat Generation – and the terrible consequence it had for people like Vollmer – is reduced to outlaw kitsch.

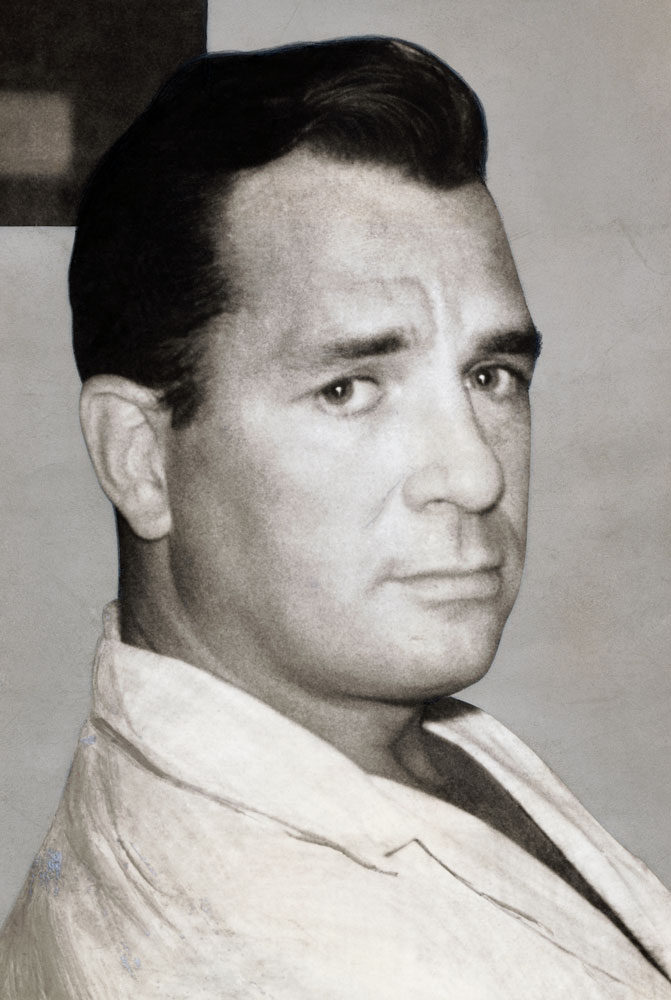

But while Beiles never achieved the literary acclaim he may have wanted, his life still became a part of the wider tapestry of radical culture in the 20th century. There is a photograph of him, available in the University of South Africa archive of his work, taken in Yeoville in 1994 as he was talking with American poet and musician Gil Scott-Heron.

Scott-Heron is a legendary figure, whose spoken-word albums were a key element in the birth of hip-hop. Twenty-six years after this photo was taken, the protesters in the George Floyd uprising in the US sang rap songs as they confronted white supremacy on the streets. They turned to this popular poetry to express their truest rage and fear, but equally, their desires for a better world.

This poetic impulse was shared by South African surrealists and American beatniks alike. It is the hope that language not be reduced to advertising and social control, but instead can be an unruly force for liberation.