Long Read | Still no justice for Soweto Derby dead

The biggest rivalry in SA football has also been the deadliest, with 87 people losing their lives in violence and stampedes at different stadiums. Yet those responsible are never held to account.

Author:

19 March 2021

Mbuzeni Zulu lifted his camera and aimed it at the crowd, which formed a sea of black and gold on this sweltering hot summer’s day in South Africa’s North West province. Fans had been arriving since early in the morning, eager to see their beloved Kaizer Chiefs and Orlando Pirates in pre-season action at the Oppenheimer Stadium in Orkney in the country’s mining heartland.

“It was not your typical crowd for a Soweto Derby,” Zulu said. “It was mostly miners, some with their families, who would not usually get the opportunity to see Chiefs and Pirates play. There was a joyous mood, people were singing and dancing. But what was unusual for me, and why I took a lot of crowd shots that day, was because the fans were sitting together – Chiefs and Pirates side by side in the stands.

“I had not seen this before. Usually it was Chiefs fans in one stand and Pirates fans in the other, but this was a friendly match arranged as a fundraiser. You know, in those days they used football to raise money for the liberation movements, the ANC and PAC, who would receive a share of the profits by way of donation.”

Zulu, now retired, was a photographer for the Sowetan newspaper and one of the few media at the venue on 13 January 1991. “It was just coming to the end of the festive season and I think everybody was still celebrating. There were so many fans, too many, and some I could see had come drunk or were drinking at the venue, which was not allowed. But everything was fine. People were happy.”

Related article:

The mood changed when Chiefs scored a disputed goal in the second half and a fight broke out between two rival supporters in the main stand. The violence quickly spread along club allegiances and it fast turned into a mass brawl.

“It happened so quickly and came from nowhere,” Zulu said. “But suddenly fans were using anything they could find to beat each other – bottles, rocks, chairs, anything that was loose. It was just so violent.”

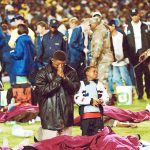

Many supporters pushed forward in the packed stand to escape the fighting, resulting in a stampede that left 42 supporters dead. “I would say most of the people who died were actually trying to flee. They were running for their lives. Many were tripped or fell and then crushed as the next wave of frightened people came over them,” said Zulu.

“And you know, at the front of the stand was a special area for people in wheelchairs or those who suffered from other various disabilities. It had been specially roped off for them. But when the wave of people came down from the stand to escape the fighting, they were knocked out of their chairs to the floor and crushed. They physically could not escape and had no chance. It was terrible.”

Zulu estimates the violence lasted 15 to 20 minutes. The aftermath was a horrific sight that left even an experienced newspaper photographer like him shocked to the core. “Bodies. There were bodies everywhere. Some beaten to death or stabbed, others crushed. Women, children… I spoke to a man who had lost his wife and son right there. He had lost them in the stampede. Can you imagine? At a soccer match…”

Zulu says the lack of a police presence could have been a factor because private security personnel were simply caught off-guard and were ill prepared to deal with the chaos. The National Soccer League instituted a commission of inquiry that was led by former chairperson Rodger Sishi. It did not apportion any blame for the disaster but made various recommendations.

These included that all stairways and access paths at stadiums should remain clear, an adequate number of security guards who remain visible at all times should be employed for matches where large crowds are expected, and they should properly monitor the crowd’s behaviour throughout.

Forty-two lives were lost and yet no one was asked to take responsibility. It was a day that changed Zulu forever. “My editor had told me that on the way to the stadium from Johannesburg I must go to Sebokeng, where the night before 39 people had been killed at a funeral [a night vigil for slain ANC member Christoffel Nangalembe]. They had been gunned down in this black-on-black political violence that was prevalent at the time.

“I went there and took pictures of the aftermath. It was hard. There was blood everywhere and the mourners were crying and angry. It was a horrible scene. After that I was looking forward to the soccer game. I hoped it would take my mind off what I had just seen. Whoever believed such a tragedy could happen at a soccer stadium?”

A tragedy repeated

The Orkney disaster sent shockwaves throughout South African sport and officials vowed that it could never happen again. But a decade on, it did. “This night is set up for a disaster to happen,” SABC television commentator Michael Abrahamson said prophetically on air as a growing sense of unease came over him.

It was 11 April 2001 and the selfsame Chiefs and Pirates were involved in a league game at Ellis Park in the heart of Johannesburg, a surprising venue for a match of this magnitude. The much larger FNB Stadium would have seemed a better choice. And by the end of the night 43 fans would be dead, crushed in a stadium that was filled well beyond its capacity.

Related article:

A commission of inquiry led by Judge Bernard Ngoepe was set up to probe the disaster. Again, the finding was that no individuals could be blamed, which was not surprising as then-president Thabo Mbeki had set the tone when he instituted the inquiry by stating clearly that it was not there to point fingers.

Instead, the commission attributed the disaster to a range of factors. These included the corruption of security guards at turnstiles, underestimating the number of fans that would be at the stadium, security organs on the night not taking responsibility for securing the outer perimeter of the venue, selling tickets on match day, and private security personnel using tear gas that created panic.

“The commission did not find it in its terms to express an opinion on what conduct, if any, would bring liability, criminal or otherwise, for the death or injury of those affected. We believe other instruments and processes will deal with these aspects,” the commission’s report said. But no one was ever charged or found criminally liable.

The Premier Soccer League (PSL) never again used two of the four security companies that were contracted to provide services that night. Its spokesperson, Andrew Dipela, who was also the match commissioner, departed for local government months later and chief executive Robin Petersen left shortly afterwards too.

Early warning signs

Abrahamson’s angst was based on an unusual start to the evening. The trip to the stadium had been eerily quiet, which suggested there would be a rush of fans at the last minute. “Normally there is a huge atmosphere from three or four hours beforehand at a Soweto Derby, but it seemed ridiculously quiet as we got to the ground, even up to half an hour before kickoff,” Abrahamson said.

The midweek evening kickoff meant many people made their way to the stadium only after work. The decision to sell tickets at the venue on the night was open to corruption and many more people than the stadium could hold gained access as they paid security guards who allowed them through the turnstiles in a deadly act of graft.

The exact number of fans inside the 62 000-seater is disputed, though the Ngoepe commission put it at 80 000 – despite the official number of tickets sold being 57 640. When the “sold out” signs finally went up, the crowd still outside the stadium turned violent. The tense situation was worsened by two early goals in the game – one for each side – as those barred entry pushed harder to get into the already teeming venue when they heard the roar from fans inside.

“The first sign that something was very wrong was when we saw a commotion in the opposite stand to where we were commentating,” Abrahamson said. “In those days, there were spiked fences that kept fans off the pitch, but people were hurling themselves over these. I knew something was very wrong, but the game was still being played and we were live on air. We had to keep going.”

The match was finally stopped at 38 minutes as the bodies piled up on the side of the pitch. “We had police running into our commentary box every few minutes, saying ‘10 dead, 15 dead, 20 dead’… it just kept going higher and higher. We were literally watching people dying in front of us. It seemed so unreal. It still does.”

The youngest victim was 11-year-old Rosswin Nation, whose parents had given him a ticket to the game as a special treat. Then there was 13-year-old Siphiwe Mpungose, whose father Veli managed to hang on to his nine-year-old daughter but lost hold of his son in the crush. He found Siphiwe shortly afterwards lying dead with a pile of bodies on top of him.

The families of the dead were heavily affected by the loss of their breadwinners and got little support. A relief fund was set up and allegedly raised R1.5 million for the relatives of the 43 victims, but this did not go far and is R1 million less than what each premier division club receives as their monthly grant today. A civil case later brought some more financial relief, but it was not much and dragged on for years.

A lack of will

Three specialist sports lawyers interviewed all agree that criminal liability for individuals would be a different ball game today with the introduction of the Safety at Sports and Recreational Events Act of 2010, which provides for long prison sentences. No such specific framework existed in 1991 or 2001. But there was the Inquests Act, which has been in place since 1959 and makes provision for criminal prosecution if a finding is made in proceedings such as commissions of inquiry. Clearly there was no will to do so.

Many at Ellis Park, including Abrahamson, were left deeply traumatised and still carry the scars. “A week later I had to commentate on a game in Durban and I just couldn’t go into the stadium. I eventually took some kind of sedative. I could not face sitting in the commentary box. I did go for counselling after that but even now I sometimes get flashbacks,” he said.

Most infuriating for the families of the victims was the fact that there had been warning signs in the years and even months leading up to the Ellis Park tragedy. In 1998, in a game between Chiefs and Pirates at the same venue, the police used rubber bullets as an estimated 100 000 fans turned up to watch and many tried to gain entrance without valid tickets.

It was a virtual carbon copy of what would occur three years later, though fortunately without the tragic consequences. Corrupt security officials were bribed to allow fans in, with supporters breaking down perimeter barriers to gain entry when they were eventually barred from doing so.

In November 2000, just six months before the Ellis Park tragedy, there were serious crowd control issues at a Wednesday night fixture at FNB Stadium when the late sale of tickets and arrival of fans saw some climb over perimeter fences to get inside, eventually tearing them down. Again, no lessons were learnt.

Related article:

The pertinent question now is whether Orkney or Ellis Park could happen again. In 2017, two fans died in a stampede at the world-class FNB Stadium during a pre-season clash between Chiefs and Pirates, crushed at a locked gate as supporters clamoured to get in. It is alleged that some had fake tickets and others no tickets at all.

Veteran administrator Ronnie Schloss, the PSL’s chief operations officer who is in charge of assessing the safety and security measures at stadiums today, believes fans are as safe as they could be at major matches, though the spectre of fake tickets remains.

“With regards to the 2017 incident, these were fans who were trying to gain entrance to the stadium once the turnstiles had already been closed as the venue was full,” he said. “This was not at the start of the match but some way in. Some might have had valid tickets, but the turnstiles count the number of fans who enter so we know exactly how many people are in the stadium, and if it is full then we do not allow any more in.”

Schloss says the major safety feature in place today compared with 2001 is the creation of an outer security ring that, in theory, should not allow fans without tickets near the stadium. But as the 2017 deaths show, it is only as effective as the individuals managing it.

Blocking an inquiry

Then-minister of sport Thulas Nxesi instituted another commission of inquiry but was replaced in a Cabinet reshuffle soon afterwards. His successor, Tokozile Xasa, stopped the probe, citing a lack of cooperation from “key role players”.

“As inquiries of these nature relies largely on the cooperation of the affected stakeholders and there has been active opposition on this one‚ the department found it necessary to withdraw the current notice and to review other available legal instruments and to vigorously pursue the matter further through other law enforcement agencies to ensure that the interests of justice for the families of the deceased are served‚ as well as to ensure that the relevant laws of the Republic are respected and observed,” Xasa said in a statement.

When the Department of Sport, Arts and Culture was pressed on why it had declined to pursue the commission, it said that Stadium Management South Africa (SMSA), which runs the FNB Stadium, had sought a court interdict against it.

Related article:

But SMSA says it has no objection to a commission – and would welcome one today. It maintains, however, that the minister has failed to comply with the Sports Act and it is a matter of process. “On a proper interpretation of the court documents, the legal basis for the application was based on the fact that in the purported establishment of a committee of inquiry, the then minister failed to comply with the provisions of Section 13(5) of the Sports Act,” said current SMSA chief executive Bertie Grobbelaar, who took on his role only after the incident.

“As clearly recorded in the correspondence, SMSA was never opposed to the establishment of a judicial commission of inquiry correctly constituted and appointed in terms of the provisions of the Commissions Act 8 of 1947, as amended.”

Letters from SMSA to Xasa show the company has been critical of the role of law enforcement in not just the 2017 incident but at other events. The South African Police Service has not responded to repeated queries over whether it is still investigating the 2017 incident.

And so it appears this tragedy, as with those before it, will see no justice for the bereaved. “You don’t go to football expecting to die,” Zulu said. “That is the tragedy here. Joy turned to despair in an instant. Thirty years on I still feel that pain.”