Matthew Krouse’s anti-authoritarian past lives again

The former actor turned editor now bookseller is slightly bemused at the interest his avant-garde films from the 1980s are garnering, but perhaps they can play a ‘functional role’ in art activism t…

Author:

4 June 2021

These days Matthew Krouse can usually be found in the bookshop he runs upstairs in the David Baillie Gallery at Victoria Yards in Lorentzville, Johannesburg. With his usual, self-deprecating and dry sense of humour, Krouse seems a little bemused at the fuss being made about things he did in his 20s. Back then, he was living the life of a gay drama student newly arrived in Johannesburg from the East Rand town of Germiston, where he was born to a Jewish mother and an Afrikaans father in 1961.

A recent excavation of several of the anti-authoritarian, avant-garde films he made – along with a selection of writings, illustrations and images produced during a flurry of anti-apartheid, pro-LGBTQIA+ and activist-centred artmaking in the 1980s and 1990s – has been curated and exhibited under the guidance of South Africa-born artist Adam Broomberg at Kunsthallo Gallery in London, England. The physical space has migrated online owing to the restrictions of the Covid-19 pandemic.

As a student at Germiston High School, “a public school with private school pretensions”, Krouse was already marked as an outsider, “a moffie”, whose parents were too liberal for his classmates’ liking and who had too many friends in cosmopolitan Johannesburg to be trusted.

He was also the target of envy because he had school colours for “art stuff” while his schoolmates were “fascist superheroes on the sports field, killing themselves for colours. I was chain-smoking with filthy fucking hands and nails, my clothing was always scrubby, I was cruising all the boys… I was real suburban trash, but I had colours for acting.”

It was acting that provided Krouse an opportunity to flee Germiston, arriving at the University of the Witwatersrand in the early 1980s where he enrolled as a drama student. He was soon caught up in the heady world of the nascent alternative theatre scene in the nearby suburb of Braamfontein.

Fellow student Andrew Worsdale and Krouse established the Weekend Theatre group in a flat in Braamfontein, where the furniture would be moved out on weekends to create an impromptu theatre space for performances of plays by avant-garde American and European playwrights.

Krouse now admits that perhaps Weekend Theatre was hamstrung by the fact that “we were severely apolitical, and that was the result of the admiration that we were giving to British and American performance culture and their performance art scene”.

On the border

Krouse’s plans for theatre glory were dealt a crushing blow in 1984, when “I fucked out at Wits. Andrew got the Fulbright and left for America [to study film at the University of California] and I bummed out and had to leave.”

When Krouse told his father that he’d come unstuck and needed to leave the country immediately to avoid conscription by the then South African Defence Force, his father told him there was no money for such a plan. But he did speak “to somebody who knew somebody who knew somebody” to secure his son a non-combatant position at the army’s services school.

Unfortunately for Krouse, he arrived to take up his position as a clerk in 1985 just as then president PW Botha declared the first state of emergency in South Africa, and all non-combatant positions were scrapped. What happened to Krouse in the army would indelibly affect his art and his life.

“There was this kind of bizarre and horrific selection that happened, in which they sent gay boys who were identified as gay to the bottom of the field to live in tents where they could watch us, this ‘queer platoon’.”

Krouse tried to keep his head down and avoid duty on the dreaded border. Although he was sent to the Namibian border for a day, he convinced a military counsellor that he was not suited to service. “Too old, too educated, too Jewish. Whatever the fuck I could say,” he recalls. He spent the rest of his army service working at 1 Military Hospital in Pretoria, where he served in the media centre, mostly compiling nursing modules.

In a story he’s told “a million times”, Krouse remembers being shocked one day by a gruesome projector slide depicting a young man who had his anus blown out after a training accident. Krouse pocketed the slide and it would later get him into all sorts of trouble with the apartheid police and censorship board.

He also spent time in the army performing in a state-sanctioned drag troupe called The Arista Sisters, which provided entertainment for the troops and which he saw as “this sanctioned moment of drag in which the army facilitated this moment of ‘moffiedom’ in order to reinforce heteronormative ideas about the female role, which was very defined in the drag”.

Famous dead men

By the time he returned to Johannesburg in 1985, Krouse was “fucking furious with everything because everyone’s lives had gone on and my life had gone fucking nowhere. Nothing had happened to me and I had no real prospects.”

Keen to develop an idea he’d had while in the army for “a Rat Pack cabaret” based on the life and assassination of apartheid architect Hendrik Verwoerd, Krouse sought out his former theatre collaborator Robert Colman. Together they developed the play Famous Dead Man, which they performed to the enthusiastic mirth of white, progressive crowds at The Black Sun in Hillbrow.

With its ribald disregard for the official version of Afrikaner history and its provocative, punk-inspired takedown of Calvinist hypocrisy around sex, Famous Dead Man did not go down well with the apartheid censors. Under pressure from the equally unimpressed Verwoerd family, they banned the play.

When Colman and Krouse then unveiled the slide he’d stolen as part of an End Conscription Campaign performance of cabaret piece Noise and Smoke, the police arrested them. In an attempt to appeal the banning order for “obscenity, blasphemy and inciting South Africans against Afrikanerdom”, Colman and Krouse performed Famous Dead Man for the censors.

The case was much publicised at the time and though the eventual finding kept the ban in place, the Verwoerd family’s claims of defamation were thrown out because, as Krouse ruefully observes, “They couldn’t prosecute us because the finding was that a dead man couldn’t be defamed. The famous dead man was dead.”

The media attention around the case made Colman and Krouse “celebrities in Braamfontein. We were in every newspaper in town and getting interviews overseas … I was the fucking hero. I thought the world of myself because suddenly I was political.”

Shot down

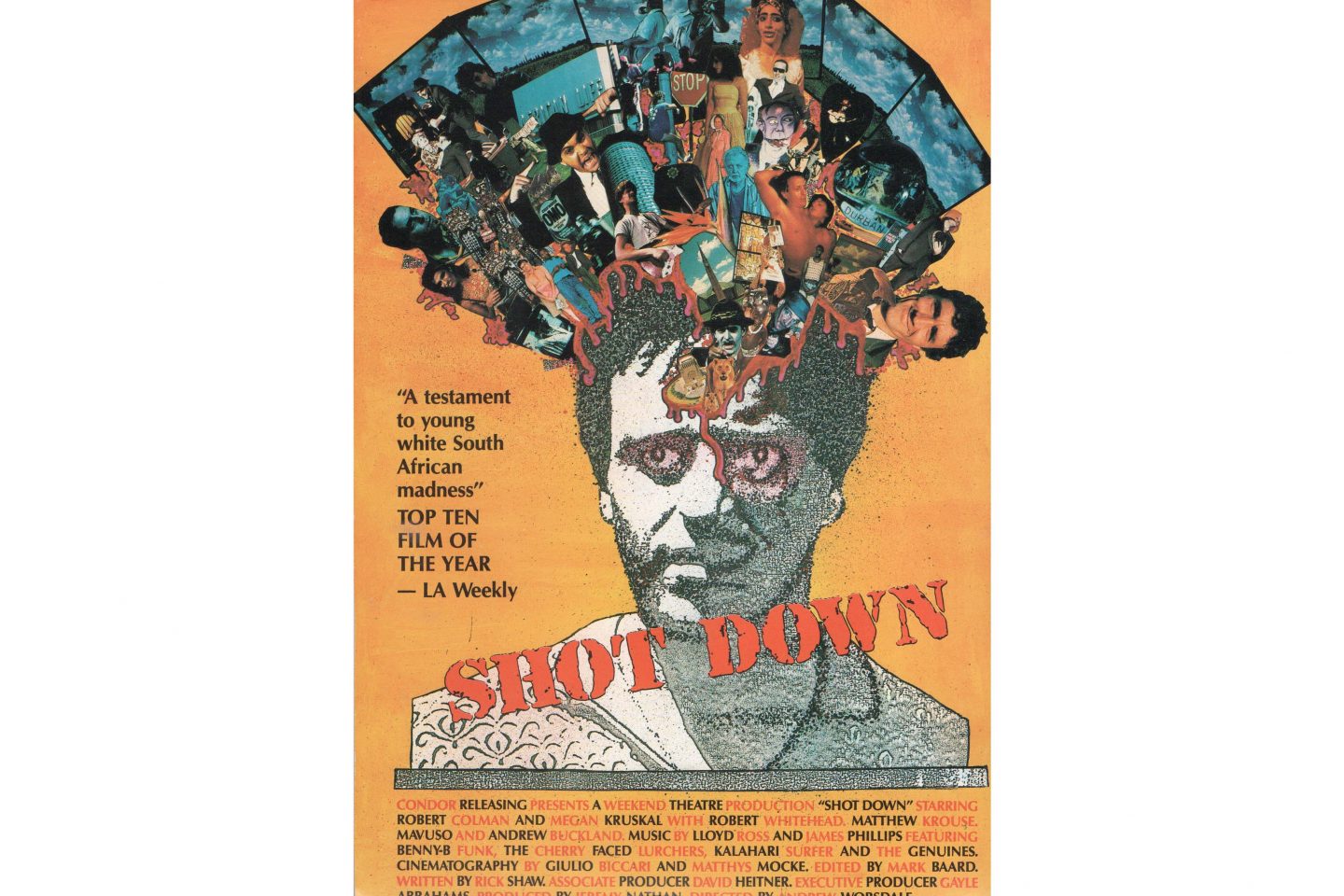

When Worsdale returned to South Africa in 1986, he found his old friend and partner in crime strutting the streets of Johannesburg, living the life of an anti-apartheid cultural celebrity with a mad bag of wild stories to tell. Together they set about turning the tumultuous, Kafkaesque calamities that had befallen Krouse into the material for a feature film, taking the title of James Phillips’ political ballad Shot Down as its title. Krouse “just assumed that Shot Down would proportionately be about me because I was the living god of anger and resistance in my mind”.

Although he would end up playing a significant role in the writing of the film, perform extracts from his banned cabarets in it and create with Jeremey Nathan a short, darkly satirical and risqué film called De Voortrekkers that was inserted into it, Krouse did not end up being the star of the film. The role of protagonist Paul Gilliat went to Colman and the completed film – a wildly anarchic minestrone soup of all the different aspects of white, anti-apartheid cultural production that was happening in Johannesburg at the time – was immediately and predictably banned.

Krouse and Nathan’s short film contribution garnered its own banning order from the apartheid censors, who wrote in their official decision: “In front of their wagon, a Voortrekker couple drop the Bible, shed their Voortrekker dress, and then they copulate while the man enters her from behind. They crawl over the ground. This lengthy scene intrudes on the privacy of the sex act. Walking naked the man finds his son and a friend in a homosexual sex-act. This is indecent and obscene. In a short film with 85% undesirable, there is no way to pass De Voortrekkers.”

Seemingly undeterred, Krouse and Nathan set out to take an even more outrageous potshot at the Afrikaner establishment with their next film project in 1988. The Soldier was envisioned as a film that “would tell the whole of the apartheid South African history book through fucking.

Using all of that Afrikaner iconography against itself and making fun of it,” says Krouse. The film included a gay rape scene, intended to be staged in the regime’s holiest of holy places – the grave of the unknown soldier in the Voortrekker Monument.

Although the crew did manage to sneak into the monument, distract the tour guide and shoot some establishing shots, the rest of it was shot on a stage at the Wits Theatre.

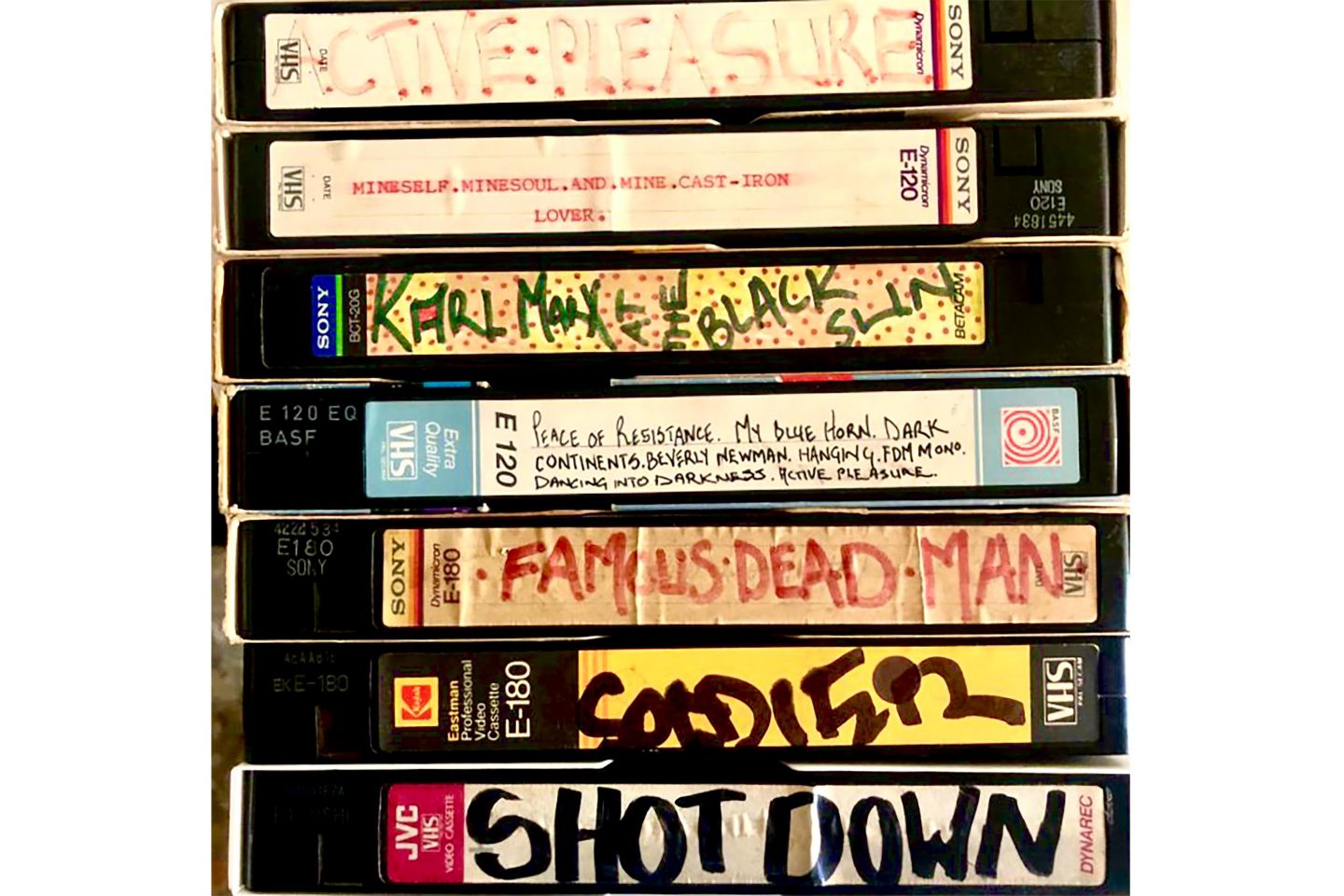

The film was smuggled out of the country to London for processing but as fate would have it, the laboratory there burned down, leaving only a few silent rushes that sat for decades on a VHS tape in a cupboard in Krouse’s flat, until they were unearthed and digitised for the Kunsthallo show.

Democratic and other negotiations

The bannings of Shot Down and De Voortrekkers and the loss of The Soldier marked an end to Krouse’s career as a maker of theatre and experimental film. By the time the 1990s arrived with the release of Nelson Mandela and the beginnings of democratic negotiations, Krouse “didn’t really know what to do. I was kind of spent. That’s when Nadine Gordimer found me and the other activist communities found me and it was like, ‘If you’re going to be this activist with a loud mouth, then you’ve got to join the struggle.’”

Krouse worked as an assistant to Gordimer when she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1991. Through her, he began to work closely with the Congress of South African Writers (Cosaw), designing book covers for works by writers in exile such as Keorapatse Kgositsile and Mongane Wally Serote, and editing poet Lesego Rampolokeng’s seminal collection Horns for Hondo.

Through his work with Cosaw, Krouse became the co-editor with artist Kim Berman of The Invisible Ghetto, the first LGBTQIA+ fiction anthology from the African continent, published in 1992. He was also heavily involved in the struggles of the LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa to obtain equal rights under the new Constitution, which, as he points out, “was not a given at the time”.

When the 1994 elections heralded South Africa’s new and miraculous democratic reinvention as the Rainbow Nation, Krouse, now a serious activist and no longer an anarchic artist, had also “fucked out massively. By 1996, I was a full-time heroin addict. I could not leave my flat without having to go and score drugs, go back and calm myself down, go back and score drugs again.” He eventually cleaned up by locking himself in his flat for two weeks and going cold turkey.

Post-apartheid, post-life

Krouse emerged from that experience to take a position as the deputy arts editor of the Mail & Guardian at the suggestion of his friend, journalist Shaun de Waal. He became the arts editor of the newspaper in 1998, a position he held until his departure in 2014.

“The thing about it was, if you want – and of course everybody now knows that it’s not true – apartheid was ostensibly dead and so for me there was no reason to carry on making the same old stupid comments over and over and over again and reiterating that point of humour. I had also become very serious by getting involved with Cosaw, who prepared me for a ‘post-life’ in the world of publication. I didn’t think of myself as an artist and I don’t really even think of myself as an artist now.”

Krouse feels that the exhibition and its tribute to his youthful angry jabs at the former regime is “fine. Some of it’s looking quite quaint. I think De Voortrekkers looks youthful and I know that it’s a good piece of filmmaking. The Soldier, I’m sorry that it was never finished. Famous Dead Man is funny in parts. They do all look a bit like vintage cars and that’s fine, I don’t mind that.”

He begrudgingly offers, when pushed, that perhaps the exhibition “may be useful for people to have a look and see that art activism can actually play a very functional role and be a creative source as opposed to just activism or just art.

People can look at it and say, ‘Well, yes, actually there are things that are unresolved in society and we can resolve them through good art making.’ And that’s great, that’s a wonderful thing. They can look at what we did and they can see how we did it and they can refute it or take some of it on board or whatever.”

As to whether or not he ever gets the urge to make art these days, Krouse says, “Every now and then I try and make something and I totally fail. I don’t have the drive. When I walked out of the newspaper, I no longer had the drive to be a critic. When I walked out of acting, I no longer had the drive to be an actress. And when I walked out of cultural art- making or political practice, I no longer had the desire. I’m a ‘mover-onner’. You can describe that however you want, I’ll be resilient about it.” And with that, the not so famous, not nearly dead yet Matthew Krouse shuffles back upstairs to carry on sorting out his books.

* To see the selection of films, publications, illustrations and images that form part of the Kunsthallo exhibition, visit www.matthewkrouse.com and www.kunsthallo.com.