Mhlambi’s images conjure jazz call-and-response

Renowned South African photographer Siphiwe Mhlambi’s Expressions exhibition of 90 large-format images takes jazz photography beyond historiography and the stage.

Author:

30 September 2020

Jazz music is a democratic high art. Its most complex compositions often baffle the highly learned and delight the unschooled. In its form, it is expansive and scholarly, yet spiritual and immensely emotive. Jazz must be felt to be understood; yet to comprehend it is not necessarily to be hip to it.

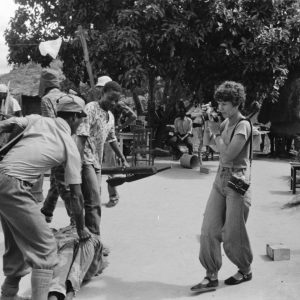

Photographer and visual artist Siphiwe Mhlambi’s recent 90-image exhibition Expressions at Foto ZA Gallery comprises portraits of South African and international jazz musicians in performance. As a collection it is both a pedestrian sidewalk and a wide, well-paved highway of jazz imagery – simultaneously accessible and high-brow. In images, jazz’s complex democracy is expressed, just as in music.

These large-scale black-and-white works require careful looking from the viewer to be understood. Each individual image has its own standalone intensity, capturing a singular moment of musical expression. Together, the body of work, photographed by Mhlambi over 28 years, presents a platform for complex and imaginative interpretation.

Related article:

Expressions is organised not by geography or history, but by mood. The first triptych – an image made up of three panels, presented as one – primes the viewer for what is to come. Lemmy Mabaso is photographed closely to show only his hands on his penny whistle – his face and Hillbrow’s Ponte Tower in the background. Next to him is placed an image of trombonist Jonas Gwangwa with his forehead wrinkled in concentration, while Hugh Masekela appears with his flugelhorn in the adjacent photograph, his eyes keenly focused on a place outside of the frame, perhaps even past this realm. Together, a moment of clear intensity is created, which is felt because it is seen. The sound is imagined by the viewer who, throughout the exhibition, also becomes a listener.

“This is my orchestra,” Mhlambi says of his self-curated body of work. “I know who is doing what, where, next to whom and how. I tell a story and I didn’t want to put [historical] captions [with the images] because they would fascinate you and put you off the story that I am trying to tell.”

What follows Mabaso, Gwangwa and Masekela’s trio are duets, quartets and quintets of Mhlambi’s imaginative making, each of them creating unmistakable and distinct atmospheres between the players for the viewer and sounds for the listener to infer.

The musician with a camera

Some of Expressions’ clearest moods and sounds are meditative, delightful, transcendental and introspective. In a duet, percussionist Selle Galane is enraptured at his instrument. He faces Kyle Shepherd who, with his hands on the piano keys, carries a focused calm about him.

In a quartet, Miriam Makeba’s face is awash with delight. Her image faces saxophonist Joshua Redman mid-solo. While next to Makeba, bassist Benjamin Jephta’s tipped-back, pout-lipped face is framed in the square created by Sisonke Xonti on his saxophone. Zim Ngqawana, back angled away from the rest of the quartet, ostensibly supports Redman’s solo across the bandstand.

Perhaps the strongest aggregation Mhlambi creates is a quintet of images, with Madala Kunene on acoustic guitar and harmonica, Tu Nokwe on electric guitar, Siya Makuzeni on trombone, Sadao Watanabe on flute and Brandford Marsalis on trumpet. Front and centre, Siya Makuzeni belts out a note which renders her instrument a rocket ship to a familiar but far-flung galaxy.

As curator, Mhlambi is aware of the spaces between the notes being as important as the notes themselves in jazz composition. He shows this deep understanding to the viewer’s or listener’s relish. Across the room from Shepherd’s “mushin” (no mind) meditation at the piano, Andre Peterson holds a similar pose directly across the room – one young master nodding to the other. Pianist and composer Paul Hamner laughs gleefully, his line of sight pointing to his longtime collaborator McCoy Mrubata across the room.

Mhlambi describes himself as a musician, but with the camera rather than a musical instrument. “I am part of the band because I play with them,” he says. “We are all in sync. By hearing the music and photographing it, I am part of it. We are all in this thing together but we have our own roles.”

In an age where the smartphone and social media have been primarily responsible for rendering instant, and often disposable images, Mhlambi’s process is, in contrast, a slower one from the fast-disappearing era of his photographic beginnings.

Hope, in a camera

At eight, Mhlambi and his brother, three years his junior, were abandoned at a house in Jabavu, Soweto. Together, the pair survived by tending gardens. Mhlambi also worked at a general dealer where scholars from the nearby Morris Isaacson High School would buy and eat their lunches. “I would be paid with fish crumbs,” he recollects. “Every day I would get a wrap of that and I would take it home… That was my life.”

On the evening of 6 or 7 May 1980, the South African government undertook a census of the population living in what were then the four provinces of the country: Cape, Orange Free State, Transvaal and Natal. On that evening, the administrator tasked with recording the details of people where Mhlambi and his brother lived noticed that the pair had been excluded. Out of concern for their wellbeing, she became the brothers’ quasi-adoptive parent, ensuring that Mhlambi would attend school for the first time at age 13 and giving him his first camera a year before.

“When the camera came around it was like this hope in a hopeless world,” Mhlambi reflects on how he learnt to use the camera and became a photographer for hire, charging subjects per image. “I would only take photos on Sundays when people were washed and wearing new clothes. I got so popular that I used to shoot birthday parties, funerals, graduations, church groups. I would bunk school every Friday, take a taxi to town, wait for the film to be developed at a one-hour lab on Smal Street [Johannesburg] because I didn’t have money to make two trips there and back. So if I took your photo this week, you would only get it after two weeks.”

It was Mhlambi’s clients who encouraged him to become a press photographer and in 1989 he began a five-year freelance career which saw him gaining access to opposing ANC and IFP factions. “Back then, what you published might cost your life,” he says. “Are you showing ANC killing Zulus or are you showing Zulus killing ANC?”

Mhlambi says that he was often alerted to the time and place of planned massacres. “The more I did that, the more I was assigned such work. At some point I wanted to die, I didn’t have a family, I didn’t have a name to live for so I would do the most daring things.”

But in 1993, in Bethal, Mpumalanga, a traumatic experience catapulted Mhlambi into magazine editorial and commercial photography. “One of my pictures was published before one of the comrades died and they thought that I had exposed the guy to the cops. They got hold of me and they wanted to bury me alive so that I can be a sacrifice for the comrade who died. That’s when I stopped working for newspapers.”

The scale of Expressions attests to the turn in Mhlambi’s career to jazz photography, and the dedication to this artform over the decades. The frugality of his photographic beginnings, where he would only be paid for the images that were successfully captured and developed, has stayed with Mhlambi.

More than an exhibition of a body of work made mostly on film, Expressions stands as a monument to an era in South African jazz photographic history where patience could bring more rewards than speed. Subjects were co-creators and moments were portals into real and imagined worlds.