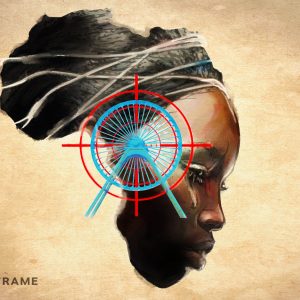

Mining brings death and division to KwaZulu-Natal

The proposed expansion of Somkhele anthracite mine has pitted residents against each other, with those against it stunned into silence after the murder of Fikile Ntshangase.

Author:

12 November 2020

MaNgcobo* refuses to have her identity published. The 73-year-old and her family are among households who were moved from KwaQubuka village in 2014 to make way for the Somkhele opencast anthracite mine in the uMkhanyakude district in northern KwaZulu-Natal.

She is scared of speaking out against the local tribal authority and the mine following the assasination of 63-year-old Fikile Ntshangase, an activist who had been fiercely opposed to the mine’s expansion. She was murdered on 22 October.

Related article:

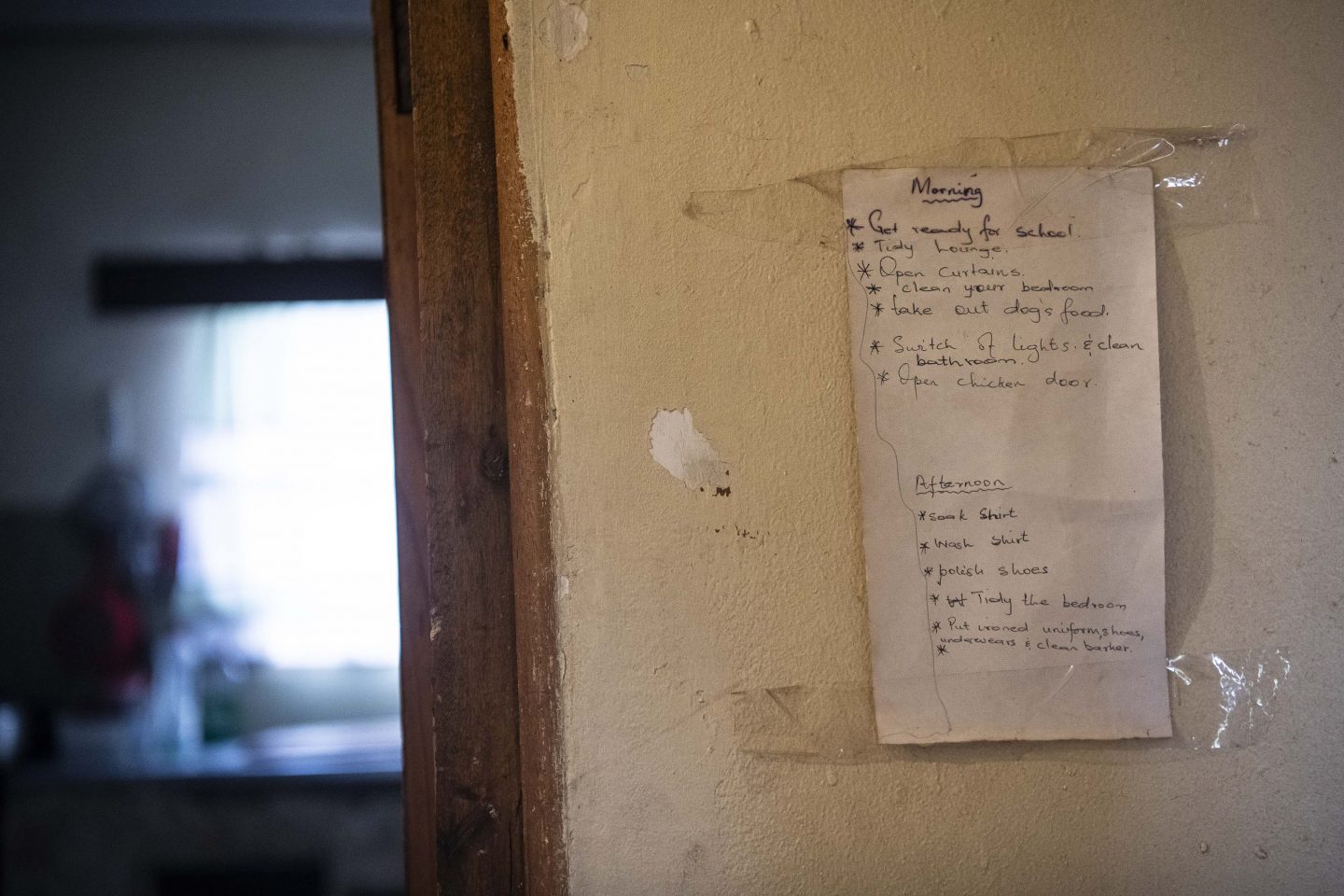

MaNgcobo and her large family were relocated to nearby Ophondweni, where they live in the shadow of the mine and its environmental and health effects. She says their lives have worsened since the move. The family used to have five homesteads, a kraal and a garage, and they were not properly compensated for them.

“The mine people cannot be trusted. They came here and promised to compensate us for all our homes, but that was never the case. They promised us job creation, but we never asked them how. Now, two family graves lie under a mine and there was nothing I could do. I made tireless efforts making applications for better compensation and the dignified removal of my family’s graves,” says MaNgcobo.

“Our entire family fell apart after the move. Many members could not all fit into this house because it was small, but what could I do? The money they gave us only got us this far. We signed our lives away because we believed all the promises on paper. And of course, when you hint at money to poor people, it is highly likely they will sign first and ask questions later. Now we suffer those consequences.”

A giant open pit

Somkhele mine is situated just 10km upstream from Mtubatuba on the Mfolozi River and is close to the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park. It is owned by the Petmin Group and run by the company’s 80%-owned subsidiary, Tendele Coal Mining. On its website, Petmin says the remaining 20% is “held by a trust for the benefit of the local community and employees”.

The mine’s operations cover an area of about 22 000ha, and its expansion has divided residents in the area, which falls under the Mpukunyoni Traditional Council. Out of 145 families that will have to be moved, 19 have not yet signed an agreement.

Mbhishobi Mkhwanazi, a member of the Mpukunyoni Community Mining Forum, claims that the social unrest that has erupted in Ophondweni is orchestrated by “white lobbyists”. The forum, which comprises about 30 izinduna (traditional leaders), supports the expansion of the mine.

“Nobody here is against mining,” says Mkhwanazi. “There are a few people involved with white organisations who claim they are representing the communities affected by Tendele’s operations. The community of Mpukunyoni has been patiently waiting for 36 months, with negotiations between the mine and residents having been delayed by court cases from white lobbyists who are against mining.

“Now, people are running out of patience. People are stuck in between the battle between the mine and parties who do not want to sign. Consequently, people can no longer bury their family members in their premises or renovate walls that often experience cracking due to the mine blasts.”

Opposition to the mine

The 19 families, many of them members of the Mfolozi Community Environmental Justice Organisation (MCEJO), are caught in a legal battle to stop all mining at Somkhele until Tendele complies with all the required environmental and other laws. In addition, the group is appealing against the additional mining rights covering about 222km² that were granted in 2016. It argues that the mine was operating illegally without environmental authorisation, municipal planning approval, a waste disposal licence and permits to shift ancestral graves.

While the tribal authority insists that the expansion will sustain jobs and skills development among youths in Mpukunyoni, some residents disagree. “They often use us and nice terms of ‘rural development and job creation’,” says an Ophondweni resident who asked to remain anonymous. “We now know that is a lie. We’ve seen it happen since Tendele mine arrived here. It has hired only a handful of people from the area. Many of them are underqualified, which means they are working generally low-paying jobs.

“The mine’s pocket gets full, and our land gets dry. Inevitably, we suffer a slow death. We have no water. These taps are just monuments, we’ve even forgotten we once had running water. The arrival of the mine was the end of our water system. We cannot rely on rainwater either because the ash deposits from the mine turn the water black.

“This community belongs to all of us, [but] we have been used and sold by our local leaders. While we want regulated and fair compensation, we also want a sustainable plan that will ensure that we are not being milked dry. As past cases would attest, it’s a trap.”

Heartbreaking loss

Ntshangase, who was the MCEJO’s deputy chairperson, was buried on Friday 30 October. Friends and family described her as a stalwart activist with a strong fighting spirit.

Among chants of farewell outside the Maphumulo Lutheran Church, the national coordinator of Mining Affected Communities United in Action (Macua), Meshack Mbangula, said: “We are weak, but this does not mean we are out. We demand justice for Mam’Ntshangase, an honest, outspoken activist who believed in fairness and equality. Her death represents capitalism at its worst – greedy individuals who claim the permission to loot using guns and violence. Mam’Ntshangase’s soul shall not rest in peace until her killers have been found.”

Ntshangase’s daughter, Nomalungelo Ntshangase, says her mother’s death has intensified the pressures brewing in mining areas. “When money is involved, people will take away whoever is in their way. My mother refused a bribe and influenced others to stand for what is fair and safe for the environment because she understood the value of land. She also could detect deception easily and was not easily manipulated.”

Nomalungelo describes her mother’s passing as “surreal”. Paging through the family’s photo album, she describes each memory of her mother, a retired teacher, often correcting her tenses. “Oh, she is, was, feisty. Strict and courageous.”

Three months ago both her parents were alive. Then her father died from cancer and now her mother is gone too. “The house was always warm,” she says. “It was always lovely to be home because my parents were in love. They loved to dance and share stories. After my father died, my mother felt lonely and didn’t want to stay alone.

“She’s always been a community activist. Wherever she was, she made sure that she was active and promoting civil action. What she always insisted on was land justice. She fought for land rights. After my father’s death, the threats intensified. Sometimes she would get private phone calls threatening her life, saying ‘uzoyithwala inhlabathi ngesifuba (your death is lingering).’

“She wasn’t too concerned until one of our neighbours, also a MCEJO member, was attacked. A week before she was shot and killed, she had started feeling uneasy, and scared at times. The threats had worsened and my mother could not deny or laugh about it any longer. A week before, she complained and reported to a close friend suspicious behaviour outside her home during the night. The next Thursday she was killed,” said Nomalungelo.

Slow wheels of justice

On 3 November, the Global Environmental Trust, joined by the Centre for Environmental Rights and the MCEJO, appeared in the Supreme Court of Appeal in Bloemfontein in an attempt to overturn a 2018 Pietermaritzburg high court ruling dismissing their application to halt operations at the mine. The case continues.

In a public statement, Tendele Coal Mining said: “Although the mine is experiencing challenges with securing new mining areas for which it has the mining rights, we remain positive that we will soon achieve a breakthrough which will extend our mining operations and the privilege to continue with similar contributions for at least another 10 years.”

Related article:

Nathi Kunene, Tendele’s community manager, says the “coal minerals were depleting, and because of that they needed to break new ground or shut down entirely, costing thousands of job losses”.

But MCEJO member Israel Nkosi says Somkhelo’s expansion should not be allowed. “The mine is riddled with challenges related to land, housing, water and the environment, coupled with non-compliance and delayed coordination from stakeholders. These factors cannot remain unresolved as they directly affect everyone in and around the mine areas on a socio-economic basis.

“When people like Fikile Ntshangase speak out about these issues, they are seen as threats because people are hungry [and] some are greedy. Both cause aggression and can lead to crime, which we have seen in the form of the murder of Mam’Fikile. Many people agree to the monetary compensations, [which are] often undervalued, and in turn they realise when the money is used up that they were used,” explains Nkosi.

In November 2016, after hearings had been conducted, the South African Human Rights Commission released a report on the underlying socio-economic challenges of mining-affected communities in South Africa. It said that mining companies who restricted compensation to the physical structures on the land were offering money “below the value considered to be appropriate in terms of the global standards” and were causing “systematic displacement and impoverishment within mining-affected communities”.

Mkhwanazi says the mine is being held to ransom by the 19 families who are resisting their relocation. “Although some people are demanding ridiculous amounts of compensation, thus delaying the negotiations, we believe we are very close to a mutual understanding,” he says.

He adds that many of the issues raised by the MCEJO will be considered as soon as everyone has signed. “We do not deny that the mine causes air and water pollution and even impoverishment. We are going to amend the original MOU [memorandum of understanding] to include recommendations on how the negative impacts, on the environment and socio-economically, can be improved. This will ensure that even after the mine has left, people have skills and notable benefits from the mine’s existence.”

*Name has been changed to protect her identity.