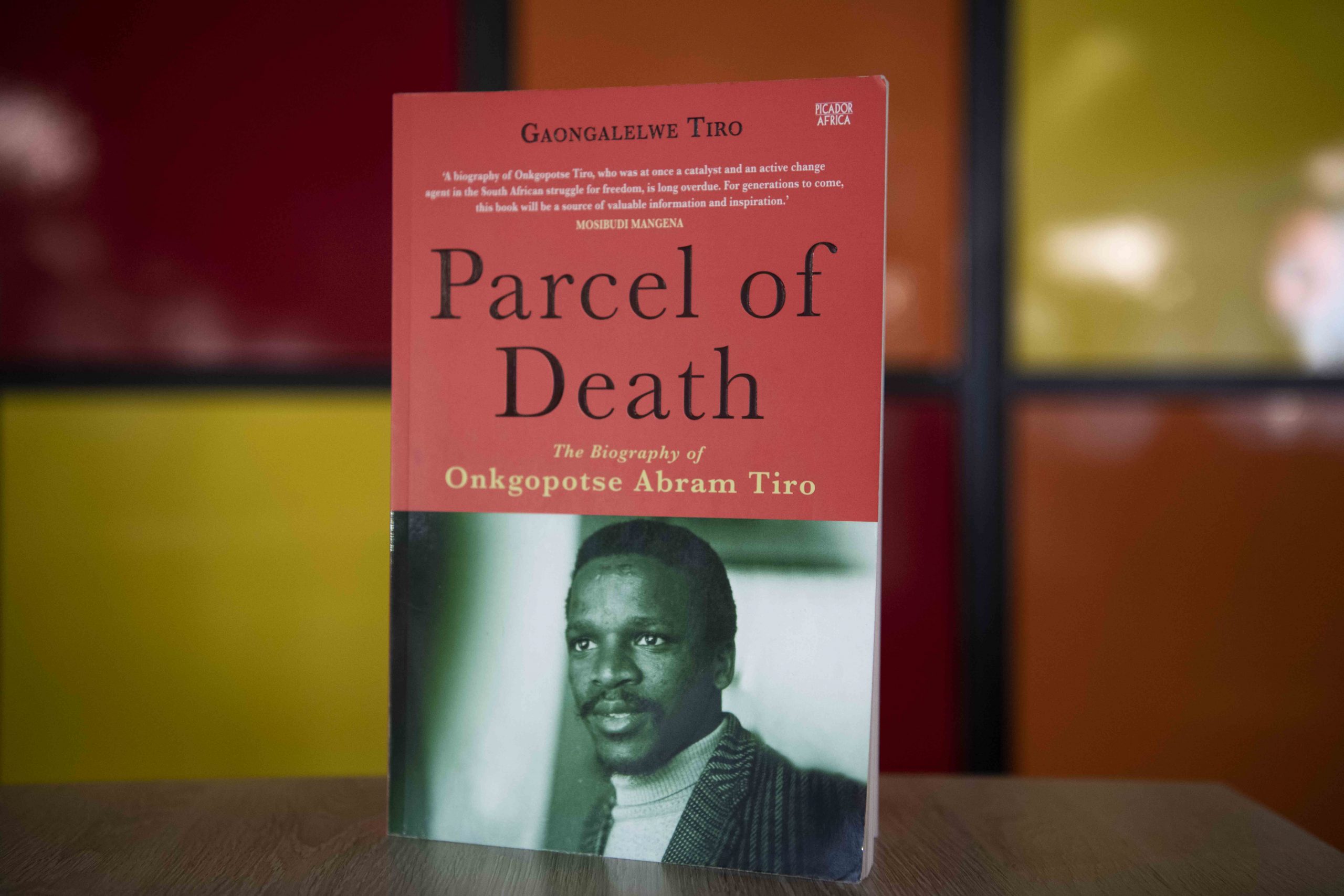

New Books | The Biography of Onkgopotse Abram Tiro

Onkgopotse Abram Tiro, biographer Gaongalelwe Tiro’s uncle, was the first South African freedom fighter the apartheid government pursued beyond the border and killed with a parcel bomb.

Author:

11 September 2019

This is a lightly edited excerpt of Gaongalelwe Tiro’s Parcel of Death: The Biography of Onkgopotse Abram Tiro (2019, Picador Africa).

Thrust into a political vortex

Onkgopotse Abram Tiro arrived at Turfloop, aged 23, in 1969 to study for a three-year Bachelor of Arts degree in history and psychology. Lack of money and the riots in Dinokana had intermittently interrupted his schooling career. When he got to university, it was in serious ferment for the first time. A coterie of individuals was trying to infuse a new militancy in the student population.

In July 1968, an opportunity presented itself when student leaders Harry Nengwekhulu and Thekiso Musi attended a Nusas conference at [the university known as] Rhodes in Grahamstown (now Makhanda). “It was there that we met student activists from other institutions and discussed the formation of a black student organisation,” says Nengwekhulu. Steve Biko and Barney Pityana were there.

Biko led a walkout of black students from the conference after differences arose between them and their white counterparts. The principal issue that cemented the rift was the refusal of the white students to sleep in black townships. “We suggested that white students should sleep in the [black residential areas] during the conference after a debate arose on where all the delegates should sleep, but they refused, saying they’d [be] arrested,” says Nengwekhulu. Apartheid policy did not allow black and white people to mix freely and, indeed, they could be arrested. However, the black delegates were having none of that because they often risked arrest by sleeping in white residential areas during Nusas and University Christian Movement (UCM) meetings.

The initial focus of the new activism at Turfloop was the abolishing of the SRC. The body had been for organising “braais and parties” and did not in any meaningful way concern itself with the broader political issues affecting black people. “We wanted to follow Fort Hare and do away with it because it was fighting to join Nusas, but we realised that the SRC notion was strong at Turfloop,” says Nengwekhulu. Students at Fort Hare had at the time rejected the idea of having an SRC. “We then decided to campaign so that when we are in the second year we are in the SRC – we strategised,” he adds. “I was elected president and Musi also became part of the leadership. We took over the SRC with the idea that we wanted to transform it.”

In August 1968, Nengwekhulu and Musi represented Turfloop at a UCM conference in Stutterheim, 70km northeast of East London. The UNB [the medical faculty at the University of Natal, for black students] group was tasked with convening the conference. “Steve [Biko] and some friends from the Allan Taylor Residence – Charles Sibisi, Aubrey Mokoape, Chappy Palweni, Mamphela Ramphele and Vuyelwa Mashalaba, among others – made arrangements to hold the inaugural conference of what became known as the South African Students’ Organisation [Saso],” writes Pityana. It sat as planned in Mariannhill, with Biko leading the deliberations. The black students agreed to cut ties with Nusas and the following year, in 1969, Saso was formally launched at Turfloop, which became its stronghold.

The organisation was not greeted with enthusiasm everywhere. “The students at the University of Zululand were reluctant because they believed that [KwaZulu Bantustan leader Mangosuthu] Buthelezi was a diplomat and that he had an ace up his sleeve and was not supporting the Boers,” says Nengwekhulu. Saso was hostile towards the Bantustans and their leaders.

The historic Fort Hare – where African struggle stalwarts including Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo, Kenneth Kaunda, Seretse Khama, Julius Nyerere, Robert Mugabe and Joshua Nkomo studied – was also not immediately keen. “It was captured by white liberals; [journalist and anti-apartheid activist] Donald Woods was a hero at Fort Hare,” adds Nengwekhulu. “Pityana came from there and they had no SRC. He had a group of people who were activists, but Fort Hare itself was [not] affiliated at the time.”

Tiro was in the hall during the Saso launch at Turfloop when black students elected Biko president and Pityana secretary. Other members of the executive were Nengwekhulu, Musi and Machaka from Turfloop, and Strini Moodley from the University College of Durban-Westville. The face of politics at Turfloop was irrevocably changed.

“Sometime in 1969 we organised our first strike over the expulsion of a male student for misconduct who had been found in the women’s hostel,” says Nengwekhulu. The decision to go on strike was controversial and not universally popular among the students at Turfloop. It, however, had some impact with the media traction that it garnered. “It was during this time that I met Tiro, who was doing his first year,” he adds. “He was one of my ardent supporters. We became friends.”

Although already highly conscious of the political situation in South Africa, it was at Turfloop that Tiro’s politics developed a revolutionary edge. He immersed himself in the nascent philosophy of black consciousness and actively participated in the newly formed Saso. He became “very militant”, says Nengwekhulu. He now preoccupied himself with struggle politics and his stature as a leader quickly grew. “One of the interesting things that Tiro told me was that because he was from a poor family, he [had had to work] in the mines,” says Nengwekhulu. “There was an anger that his political energy was suppressed by the fact that he worked in an environment where he could not even talk to the miners those days.”

Saso students drew ideological inspiration from various quarters and read widely. But there were several fundamental influences. “[They] studied Frantz Fanon’s analysis of the psychological impact of colonialism, Jean-Paul Sartre’s dialectical analysis, [Kenneth] Kaunda’s African humanism, and Julius Nyerere’s version of African socialism, which emphasised self-reliance and development for liberation,” writes academic Leslie Anne Hadfield. “They also read the work of black American authors, particularly identifying with the black power movement (even adopting the raised fist as a gesture of black pride in South Africa) and the black theology of James Cone. Saso students also drew upon the writings of Brazil’s educationalist Paulo Freire from which they derived the idea of ‘to conscientise’ – to awaken people to a critical awareness of their situation and their ability to change their situation.”

Nengwekhulu posits that global conditions at the time favoured the resurgence of struggle politics. “The winds of change” blew across the world in the late 1960s, renewing the hope of black South Africans. The Americans staged massive protests against their government over the war in Vietnam, he recalls, and the culture of protest caught fire in other places too, including Jamaica where university students went on the rampage in what came to be known as the “Rodney Riots”. The Jamaican government had declared Guyanese African Studies academic, black power activist and author of classic text How Europe Underdeveloped Africa Walter Rodney persona non grata. It believed that he was poisoning the poor with his socialist ideas and prevented him from returning to his teaching post at the University of the West Indies after attending a conference in Canada.

But, more importantly, there was growing international solidarity and awareness of the political situation of blacks in South Africa. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) had banned the country from participating in the Olympics because of its discriminatory policies that allowed only white athletes to represent the country. This growing solidarity buoyed the spirit of black students in South Africa who were acutely aware of these global developments. The civil rights movements, the Black Panthers and the whole black power movement in the US were significant influences too, germinating seeds of resistance among black students in South Africa, according to Nengwekhulu. Bokwe Mafuna agrees that the influence of the black power movement in the US was key. “I was staying in Alexandra … and we had a group going of friends that used to discuss our political situation here in South Africa,” he says.