New Books | The decolonisation of Bolivian history

Indigenous movements in Latin America tapped into centuries-old veins of oral memory to produce histories of resistance, wielding them as tools to radically transform society.

Author:

17 May 2019

After centuries of colonial domination and a 20th century riddled with dictatorships, indigenous peoples in Bolivia embarked upon a social and political struggle that would change the country forever. As part of that project, activists took control of their own history, starting in the 1960s, by reaching back to oral traditions and then forward to new forms of print and broadcast media. The book excerpted below tells the fascinating story of how indigenous Bolivians recovered and popularised histories of past rebellions, political models and leaders, using them to build movements for rights, land, autonomy and political power.

This is an edited excerpt from Benjamin Dangl’s The Five Hundred Year Rebellion: Indigenous Movements and the Decolonization of History in Bolivia (AK Press, 2019).

A world shaped by colonisation and conquest

The Western conquest and colonisation of what is now Latin America and the Caribbean is a story of blood. It is a story of genocide. It is a story of the colonisers’ attempt to completely destroy and enslave a continent of people and to crush cultures that were thousands of years old. After Columbus famously “discovered” the Americas, Hernán Cortés defeated the rulers of the Aztec empire in 1521. The Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro captured Incan emperor Atahualpa in 1532, brutally massacring his followers and looting Incan gold. At the time of the Spanish invasion, the Incan empire – and its Quechua language – spanned the Andes, and the Aztec capital had a larger population than Madrid.

The Spanish conquest was a turning point for the region. In the Andes, the Incan empire was destroyed, and the ayllus – centuries-old forms of community organisation in the Andes – were broken up into smaller, centralised communities to facilitate the extraction of taxes, land and labour. Thousands were sent to the mines in Potosí (in modern-day Bolivia) for the silver that empowered the Spanish empire. Though indigenous resistance continued, the great civilisations of the Aztec, Maya, Inca and countless other indigenous communities spanning the hemisphere were all but vanquished under the boot and plunder of colonisation. The Americas would never be the same.

We live in a world shaped by conquest. For much of modern history, Western powers conquered, colonised and controlled the Global South. Edward Said writes that by 1914, “Europe held a grand total of roughly 85% of the earth as colonies, protectorates, dependencies, dominions and commonwealths. No other associated set of colonies in history was as large, none so totally dominated, none so unequal in power to the Western metropolis.” The overarching goal was the extraction of labour and profit from Africa to Asia, from Brazil to Cuba.

These centuries of exploitation have had their victims. But they have also had their rebels. For as long as Western powers have been occupying and colonising the Global South, people have been rebelling against this conquest, sometimes violently, sometimes peacefully. They have met guns with guns, slave labour with insurrections, plantation and factory exploitation with strikes and flight, as well as everyday forms of resistance in the streets, in the home and in the government palace.

Over time, the colonised rose up against colonial powers, overthrew them in revolutions, and built independent and sovereign nations. This global political process of recovering sovereignty following colonial rule has been called “decolonisation.” As a political process, decolonisation has generally involved forming an independent nation-state, constitution, flag, set of laws and political system based on the dreams and beliefs of that nation’s local people. The global road toward decolonisation has been anything but simple. Indeed, it has been one of the most dramatic and consequential processes in modern history.

One of the first waves of decolonisation took place between the late 18th century and early 19th century in the Americas. During this time, the British were forced out of what is today the United States, and revolutionaries ousted the French from Haiti and abolished slavery in that new nation. In the early 1800s, independence wars against Spain raged throughout Latin America. Those conflicts led to the birth of new, independent nations, from Venezuela and Colombia to Argentina and Bolivia. The second wave of decolonisation took place in Europe between 1917 and the 1920s, after the collapse of the Russian and Habsburg empires. Following World War II and into the late 1970s, freedom from European colonial rule was won among colonies throughout Asia, Africa and the Caribbean.

“Let us leave this Europe, which never stops talking of man yet massacres him at every one of its street corners, at every corner of the world,” the great decolonial thinker Frantz Fanon wrote. For many, decolonisation was a process of self-determination, of leaving Europe behind rather than trying to build a society in its image. As Fanon wrote, “The Third World is today facing Europe as one colossal mass whose project must be to try and solve the problems this Europe was incapable of finding the answers to.”

Yet in many new nations, once the old oppressors were ousted from power, new ones filled their places. Elites in newly founded countries quickly seized power and used the vestiges of the colonial system to continue exploitation under a new flag. Meanwhile, foreign and national companies continued the colonisation of the globe with their conquest of natural resources, cheap labor, land, mines and oil reserves. Indigenous people were still sent to the mines; the poor were sent to the factories and sugar plantations – and often massacred or jailed when they refused to obey. In the Americas, Andean Oral History Workshop member and Aymara historian Carlos Mamani explains, “The colonies, now converted into republics, developed processes of ethnic cleansing through ‘Indian wars’, which were no more than raids that cleared out certain territories for the settlement of colonists brought in from Europe. This was the crude, cruel and bloody history up until the first decades of the 1900s.” Colonisation continued for the dispossessed of the earth.

From the Maya of Mexico to the Mapuche of Chile, indigenous communities are still resisting. Today they are against mega dams and soy plantations that displace their communities, the mines that poison their rivers and land, and the local and foreign military repression that riddles their communities and lives with bullets and violence. After facing a genocidal conflict from the 1960s to the 1990s that left 200 000 dead, the Maya of Guatemala continue to resist further displacement and violence. The Mapuche of Chile continue to organise against mega dams and dispossession. The indigenous people of Brazil face down enormous deforestation and displacement as cattle ranchers, loggers and soy farmers continue their conquest of the Amazon. The politics of extraction – linked to global capitalism and imperialism – requires the ongoing oppression of Latin America’s indigenous people.

Colonialism robbed indigenous people of their land, gold, culture and political institutions, but also of their histories. “The indigenous have always been treated as ‘savages’, as non-men, as people without history and without collective memory,” according to Bolivian sociologist Pablo Mamani. The colonisation of the Americas was an erasure of indigenous historical narratives and worldviews, a silencing of indigenous voices, a forced amnesia. “Since the beginning of the European invasion until today, social groups affiliated by descent or by circumstance to Western civilisation have sustained historical projects in which there is no room for local [indigenous] cultures to flourish,” theorist Javier Sanjinés explains. “The coloniality of power and the coloniality of knowledge, cognitive expressions inherited from the conquerer, do not permit one to see or to invent any other path.” In the eyes of the coloniser, the indigenous peoples’ inferiority was unquestionable; they were a people without a future or a past.

Today, Bolivia is home to over 38 different indigenous groups. The largest among them are the Quechua, Aymara and Guaraní. Indigenous people make up roughly half of the population; historically, roughly that same percentage lived under the poverty line. This disparity reflects the apartheid in the nation, where a small elite of European descent ruled over the majority of indigenous people, leading to the perception of “two Bolivias” – one oppressed indigenous nation and one made up of the elite holding political and economic power. “The official nation is the modern one that the mestizo-criollo elite endeavours to create,” Sanjinés writes. “It is the Western nation from which the world is described and known. The entire Bolivian educational system corresponds to this epistemological position. The other nation, the postponed nation, is the one upon which epistemological power is exercised.”

Such a system of racial oppression and control speaks to the legacy of colonialism in Bolivia. Following the Spanish conquest, colonised peoples were “condemned to orality” and could only express themselves “through the cultural patterns of the rulers,” explains theorist Aníbal Quijano. Literacy was wielded and monopolised by colonial elites as a tool to rule over the indigenous masses; to read and write in the language of the colonisers was to control the historical account. “The means used to legitimate and cover up crimes has primarily been through the monopoly of writing; whoever has the ability to write, print reports, newspapers and books has the capacity to impose their own truth,” explains Carlos Mamani. “Colonial states require policies of cover-up and forgetting, not talking about their own crimes, genocide, just as the unjust Indian wars are conveniently hidden behind celebrations such as the bicentenaries of national independence.”

Combating such erasure and silencing, and recuperating knowledge of the precolonial past, has been a central part of the wider process of decolonisation. As Fanon writes, the “passionate quest for a national culture prior to the colonial era can be justified by the colonised intellectuals’ shared interest in stepping back and taking a hard look at the Western culture in which they risk becoming ensnared. Fully aware they are in the process of losing themselves, and consequently of being lost to their people, these men work away with raging heart and furious mind to renew contact with their people’s oldest, inner essence, the farthest removed from colonial times”.

Decolonising history, mobilising the past

The decolonisation of history has long been a fundamental part of indigenous people’s 500 years of resistance in Latin America. This was a struggle against forgetting, against the silencing, maligning and marginalisation of indigenous histories of resistance, of histories begun long before the arrival of the Spanish. Decolonisation meant recovering these histories, strengthening them and using them as tools to fight the oppressor. For many indigenous Bolivians, remembering was resistance.

The decolonisation of history in Bolivia has involved indigenous activists challenging the elites’ version of history and decentering historical authority from the university, professional historians and political leaders, so activists can build their own narratives of the Andean past. These indigenous scholars looked to oral history, myths and collective memory as sources to fill in the gaps left by the official account. They decolonised history by looking to each other, to community elders and ancestors, for histories that had been passed down from generation to generation but were not accounted for in the libraries and archives of the nation.

History was decolonised by these indigenous protagonists through their transformation of historical discourses of indigenous inferiority and victimhood – narratives used to suppress indigenous identity, assimilate indigenous people and silence their past – into stories of glorious preconquest civilisations, traditions and political philosophies kept alive for centuries, and into histories of rebellion and defiance. In these stories, indigenous people were not victims without a past; they were heroes and the heirs of Andean utopias.

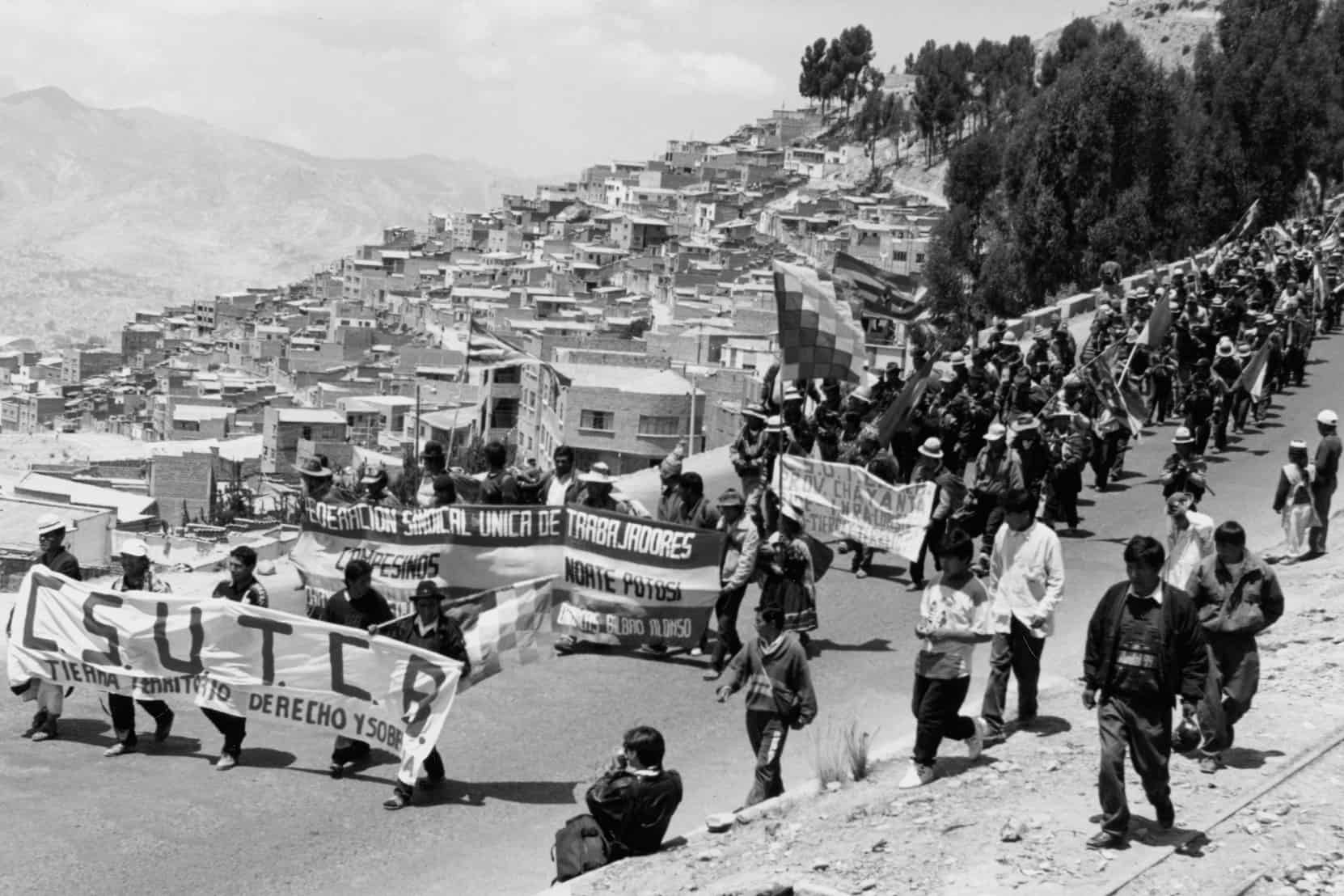

Indigenous activists took history out of the dry textbooks, the condescending political speeches, the ivory tower and put it to use in the street, where it was made to be something alive and popular, for political uses, for indigenous liberation. It was produced by indigenous historians in Aymara, Quechua and Guaraní, and published in accessible pamphlets; histories of 18th-century indigenous leader Túpac Katari and other rebels were broadcast in indigenous languages over the radio. Historical knowledge was decolonised by recovering indigenous traditions and governance models in order to bring back the centuries-old networks and political organisation of the ayllu. Indigenous histories of resistance were deployed by activists in street barricades, banners, protest symbols, speeches and manifestos. Decolonised history was on the march.

“Coming to know the past has been part of the critical pedagogy of decolonisation,” Linda Tuhiwai Smith, a Maori indigenous scholar, writes. “To hold alternative histories is to hold alternative knowledges. The pedagogical implication of this access to alternative knowledges is that they can form the basis of alternative ways of doing things.” In Bolivia, this process constituted, as one example, an alternative way of organising political power through the ayllu and rotational leadership and an alternative set of social relations based on Aymara practices of reciprocity. The past provided raw materials to postconquest indigenous communities for imagining a different world, for developing new ways of thinking and talking about alternatives, and for creating a lens through which to critique and understand the present.

“Decolonisation must offer a language of possibility, a way out of colonialism,” Smith writes. This language, which “allows us to make plans, to make strategic choices, to theorise solutions imagining a different world, or reimagining the world, is a way into theorising the reasons why the world we experience is unjust, and posing alternatives to such a world from within our own world views”. A first step in Bolivia was recovering indigenous histories. The gathering of oral history provided powerful resources to Bolivian indigenous activists building such alternatives.

For the Andean Oral History Workshop (THOA), a grassroots indigenous-led research organisation formed in La Paz, Bolivia in 1983, and other groups examined in The Five Hundred Year Rebellion, oral history offered a bridge between generations, a way to share stories of oppression and resistance and, as a result, move people to take action. It was an avenue for the recovery of indigenous voices and histories that were not accounted for in the existing written histories. The written record typically favors the elite, those with power, while oral history, writes oral historian Paul Thompson, “makes a much fairer trial possible: witnesses can now also be called from the under-classes, the unprivileged, and the defeated”.

As the THOA demonstrated through its oral history-based publications and radio programmes on indigenous resistance, oral history’s strength is typically not in the facts it provides but in its window into the meanings, motives and emotions behind historical experience and how it was lived. Indeed, oral historian Alessandro Portelli argues that oral history’s departure from fact may be one of its strengths, “as imagination, symbolism and desire emerge” from the oral testimony. For the THOA, this aspect of oral history provided a way to explore the relevance of myths within oral accounts of indigenous resistance. The organisation’s embrace of oral history could be linked directly to oral traditions in rural Bolivia, Aymara conceptions of cyclical time, and the relevance of historical consciousness to the era’s indigenous movements.

The group’s methods filled in silences and gaps in the historical record in a process of decolonising history. As Humberto Mamani, a THOA member, explained, their organisation’s recovery of indigenous histories of resistance “was like gathering different parts of a letter torn into many pieces, and when it was put together, we could read all of them and say, ‘This is our history.’ This is the history that we did not know, that was divided in many parts”.