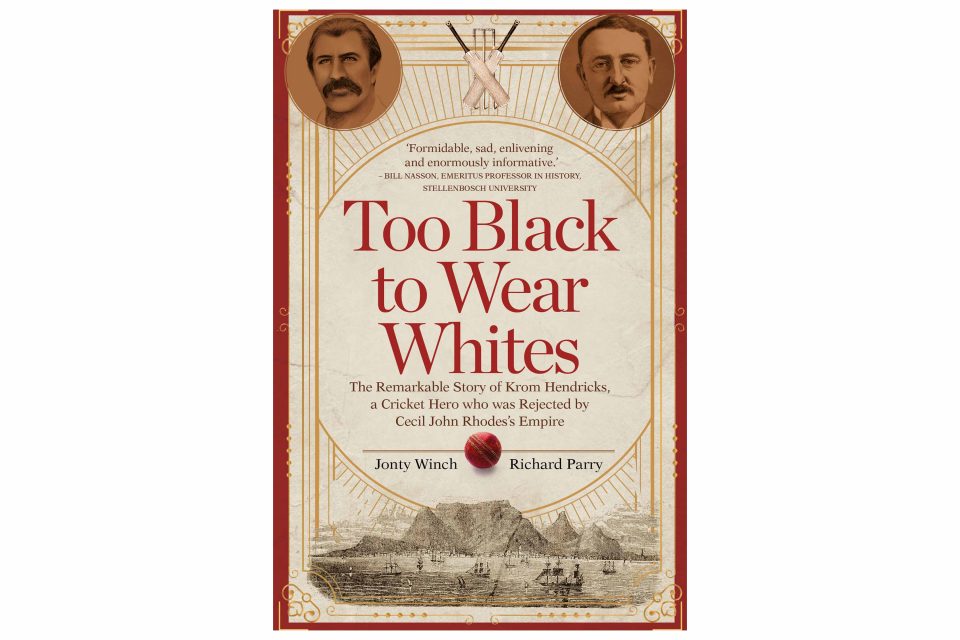

New Books | Too Black To Wear Whites

Krom Hendricks was the first sportsperson to be barred from representing South Africa on the basis of race, even though he was touted as one of the world’s greatest fast bowlers.

Author:

29 May 2020

This is an excerpt from Jonty Winch and Richard Parry’s Too Black To Wear Whites (Penguin, 2020). Published with permission.

Origins of a legend

On the evening of 3 January 1892, more than 3 000 jubilant cricket fans streamed towards Cape Town station. Elated Malay supporters came from Bo-Kaap, District Six and Woodstock to celebrate the triumphant return of their Union Cricket Club (CC) from Kimberley. Cricket was a ritual as well as a recreation and provided the social glue that bound together the community. Male choir clubs and bands in elaborate costumes led processions down the narrow avenues. The station was alive with song and music, interrupted by the wild cheering that greeted the arrival of the Kimberley train. Fans crammed the station platform, jostling for position to welcome back their cricket heroes, who shook off the dust and soot of the long journey and tumbled into the throng of well-wishers.

The tidal wave of humanity swept towards the Parade where a chorus of demands to display the newly acquired silverware punctuated the warm summer air. Abdol Burns, the half-Scottish half-Malay president of Union CC, delightedly held aloft the gleaming Glover Cup to riotous cheers and applause. The underdogs from Cape Town had dramatically defeated the might of Kimberley in its own backyard. For Burns, the victory was a combination of talent, team spirit and the passionate support received from those gathered on the Parade. But it was also a triumph for unity beyond religion. Cricket was a means of breaking down barriers and strengthening the coloured community, both Muslim and Christian.

Related article:

Burns hailed the turnaround in fortunes since the first Glover Cup contest, played at the Diamond Fields (as the region around Kimberley was known) some nine months earlier. In that inaugural inter-town competition, Robert Grendon – a Christian of Irish-African parentage – had scored a brilliant 111 out of a total of 191 to lead Kimberley to a convincing victory. This time, Burns had decided to fight fire with fire and called upon Krom Hendricks to strengthen his Union club against Kimberley’s best players, mainly drawn from the Red Crescents. Hendricks, a Christian from Bo-Kaap’s Star of South Africa CC, formed an unstoppable strike force with the impressive Ebrahim Ariefdien. They destroyed the strong Kimberley batting line-up, steamrolling them for 41, Ariefdien claiming six for 13 and Hendricks four for 24. Cape Town replied with 106 (Ariefdien 26), which provided a commanding if not unassailable 65-run lead. It gave Hendricks the chance to become a new star in the cricket firmament. His intimidating deliveries flew from a length off the matting laid on rolled red earth, forcing his opponents onto the back foot and opening their defences to a venomous yorker. In an innings analysis of six for 39, all six of his dismissals were clean bowled, including the classy Grendon who top-scored with only 24 in Kimberley’s 91. Cape Town were left to knock off 27 runs to secure victory and won with nine wickets in hand.

The bare details of the game do not describe its intensity or its drama and excitement. Rivalry on and off the pitch between Cape Town and Kimberley was exacerbated by incidents in a game that was played at fever pitch. The umpires (the Powell brothers), who were pillars of the white Kimberley cricket establishment, stoked the strength of feeling among the Cape Town travelling support. They had apparently planned to neuter the visiting side by no-balling both of their match-winning fast bowlers, Hendricks in the first innings and Ariefdien in the second, for throwing. This tactic failed to win the game in the end, but it clearly upset Ariefdien, who bowled just five overs in the second innings without taking a wicket.

“Feeling ran very high,” said the Cape Times. Such outrageous partisanship demonstrated the lengths that Kimberley – or, more accurately, the tournament sponsors – were prepared to go to keep the trophy on the Diamond Fields. The Glover family, who ran a sports and entertainment business based around the Pirates ground, was only too keen to expand its market and encourage cricketers of whatever race or religion to spend their money at the club. The Glover Cup, which the Glovers valued at 50 guineas, was intended to attract lucrative cricket business to Pirates. They had no desire to see their investment head south in the hands of their bitter rivals and to lose control over the Glover Cup competition and the lucrative inter-town coloured cricket market.

Under Abdol Burns’s effervescent leadership, the coloured cricket community in Cape Town was a force to be reckoned with in a sport that the colonial establishment held in almost sacred regard. Malays had always been subject to social and economic segregation, which separated them from the middle classes. As descendants of freed slaves, they had few economic resources to challenge the colonists, and theological differences meant they were permanently at odds. Nonetheless, Burns sought to simultaneously support the Malay community and build a broader coloured base. He was the community spokesman and fought the city council for decades to retain a cemetery on Signal Hill near enough to District Six and Bo-Kaap to allow bodies to be carried on foot by mourners, as required by Cape Muslim tradition. He encouraged regular cultural performances based on Turkish Muslim traditions, including music and Khalifa. He also worked to strengthen the wider community of Christians and Muslims who lived, worked and played together in Bo-Kaap, District Six, Woodstock and across the Cape peninsula. He strove for community acceptance, combining active engagement in the political process – supporting liberals such as Saul Solomon – with a focus on celebrating empire as good imperial citizens.

Related article:

The casual, deeply entrenched racism of the ruling-class establishment meant that whites generally paid little attention to either Muslim or coloured culture. They made no effort to consider who was of “Malay” descent, who was Muslim and who was Christian. Members of the coloured community were heterogeneous by racial background, culture and class grouping. They were categorised less by what they were than by what they were not – that is, middle-class Anglo-Saxon immigrants or their descendants. Coloureds populated Cape Town’s lower social classes, but some, through religion and skin colour, assimilated into the skilled or unskilled European working classes.

Cricket was one means through which coloureds might have sought the economic advantages that followed entry into the white working class. When the first Malay inter-town cricket tournament was organised by Burns in January 1890, it prompted an editorial from the Cape Times. The newspaper commented on “olive-complexioned cricketers” whose younger generation had taken enthusiastically to the game in recent years and would be observed with interest. The “Malay people”, said the writer, were “capable of a higher degree of civilisation than the simpler African races, of that there can be no doubt”. He admitted: “However we may have lamented the spread of the Asiatic influence in Cape Town, we have always had a saving cause for the Malays. They have not come here to try their own fortunes against the Europeans; but their fathers were brought here against their will as slaves for the convenience and comfort of our predecessors, and they have the same right to regard this country as their home.”

This leader article, probably written by the editor, Frederick St Leger, was characteristically condescending in tone and its racist rhetoric followed the prevailing model of higher and lower standards of civilisation. Where the coloured community stood was the essence of the Cape Town social battleground. For the “liberal” St Leger, the Malays had become “an integral part of the population of Cape Town … they have proved themselves most worthy”. But being an integral part did not mean unqualified acceptance. The arrangement through which Malays played at Newlands was contentious. The Cape Times reported that “several people occupying some standing in Cape society have indicated their disgust and others their surprise at the action of the Western Province CC in allowing the Malay cricketers the use of Newlands”. Some were “perfectly scandalised at the idea that so large a number of respectable persons actually found their way to matches and so gave countenance to the action of the Western Province CC”. There were other comments in the columns: “‘What next?’ exclaimed an indignant dame. ‘Where will respectable people be able to go? I expect the Malays will go and call on the Governor next’. A shrill voice was heard in the carriage-park: ‘Oh I say, it is a decided shame to allow the Malays to play on the beautiful ground at Newlands. Let them go to the Flats that’s their proper place.’”

Related article:

William Milton’s spokesman on cricket matters, Thomas Lynedoch Graham, answered the complaints in a letter to the newspaper. A decade later, Graham would become the colonial secretary [CC] responsible for overseeing the removal of hundreds of mixed-race residents from District Six, an action repeated several times until its ultimate demolition. But, as secretary of the Western Province CC, he could not afford to ignore the bottom line. After all, Newlands had been purchased a mere five years before and financing was proving to be difficult. He noted that an estimated 5 000 spectators attended the tournament, adding that their conduct “has been admirable … an entire absence of rowdiness, not a single policeman employed on the ground … In no case was the rules of cricket infringed or the decision of the umpires criticised”. He defended his club against the criticism it had received in the press, openly stating that they needed to pay for the ground. He did not “in any way regret their action in lending the Malays the use of their ground, whereas the share of the gate money has been a welcome and needed assistance to the funds of the club. As to the cricket itself, the comparatively high standard of excellence attained is a matter of surprise, considering that it is only within the past few years that cricket has been played by the Malays as a body … I may add that the get up of the players, barring an odd pair or two of braces was flawless.”

Times would change, but in the early 1890s there was no reason for Krom Hendricks to believe that he was jeopardising his future in the game by playing with Malay cricketers. He had grown up in Bo-Kaap with the players and was part of the community. Abdol Burns had offered him the opportunity not only to play representative cricket to a high standard, but also to impress at Newlands. Hendricks’s ability as a fast bowler was attracting attention and he was playing matches before large crowds. Further opportunities were to come his way …