New Books | War Party

A report into political killings in KwaZulu-Natal is largely ignored as councillors fighting for money and to keep their positions murder rivals in the ANC.

Author:

12 August 2020

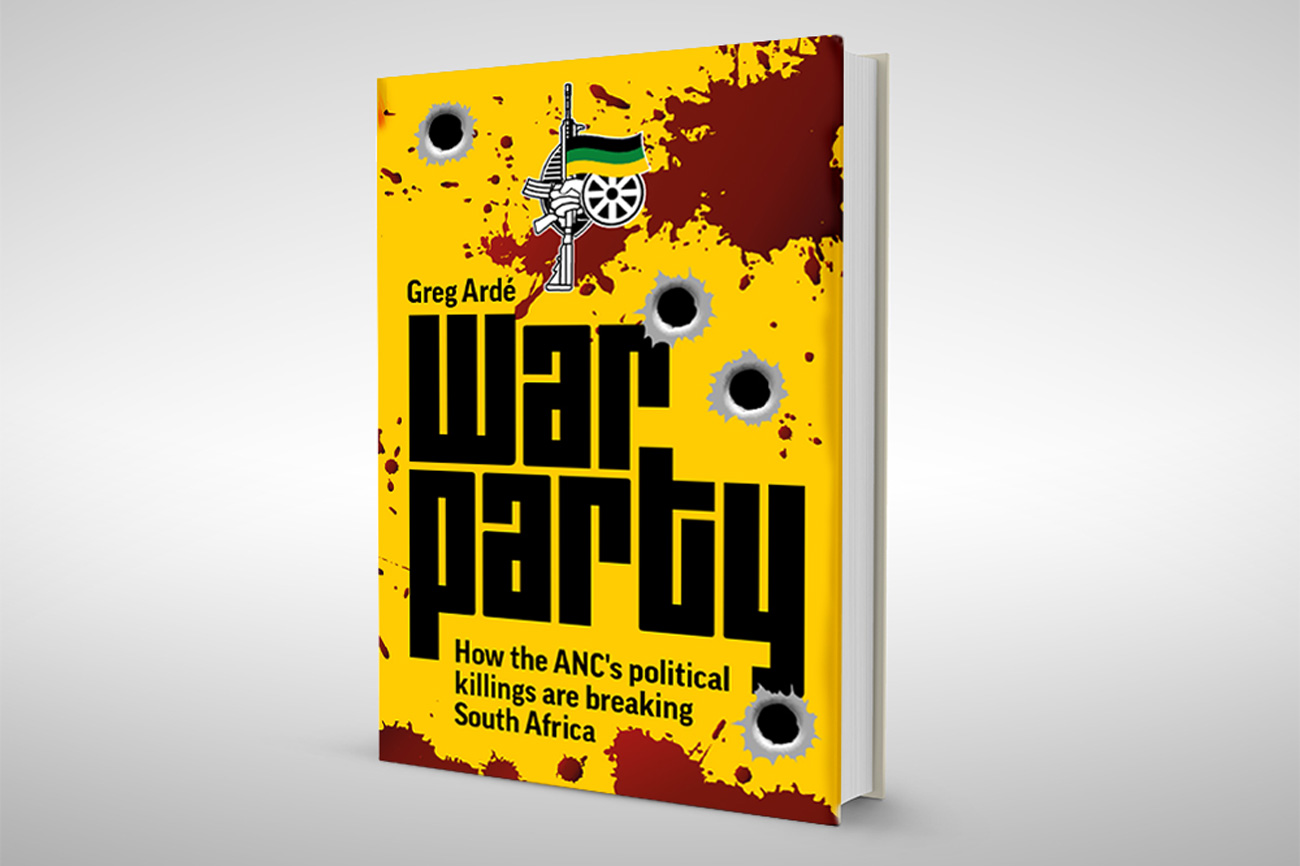

This is a lightly edited excerpt from War Party: How the ANC’s Political Killings are Breaking South Africa (Tafelberg, 2020) by Greg Ardé.

Reports gathering dust

In 2016 the government responded to the growing violence in KwaZulu-Natal by appointing a commission of inquiry headed by Advocate MTK Moerane. The commission made some valuable findings, which ought to be accepted and implemented. Instead, Moerane’s report seems to be largely ignored by government, like other victims of political violence.

In the hubbub of South Africa, Advocate MTK Moerane isn’t likely to stand out. He’s not a politician, for starters. The sprightly 77-year-old is a gentle, even-tempered man, a lawyer whose father was principal of the prestigious Ohlange Institute in Durban. He took silk some 25 years ago and has served as an acting judge. He has also been a long-standing member of the Judicial Service Commission, which chooses South African judges. In 1998 he led a commission probing the Shobashobane massacre which took place early on Christmas Day in 1995. Then an IFP impi swamped ANC-sympathising rural homesteads on the KwaZulu-Natal south coast and slaughtered 19 people. They razed the homesteads. The survivors were maimed and psychologically scarred for life.

Eight people were eventually jailed for the massacre and Moerane submitted a report to the government after his probe. He later said it was never made public and was “gathering dust somewhere”. At the time there was a rapprochement between the ANC and IFP, which may have led to the spiking of the report. Twenty years later Moerane headed up another commission, this time into political violence in KwaZulu-Natal between 2011 and 2017. Precious few have taken heed of what Moerane had to say. His report is a damning indictment of the politics of KwaZulu-Natal. What the situation portends for South Africa is terrifying. Whereas the Shobashobane massacre was symptomatic of inter-party political violence, the Moerane Commission examined intraparty violence, mostly ANC comrades at war with one another – violence transformed from battles to assassinations. The commission was established in October 2016 at the behest of the provincial government to probe the underlying causes of killings perpetrated with a political motive in KwaZulu-Natal. It heard testimony from 63 witnesses, including academics, violence monitors, anti-corruption activists, police and others, and produced a report in March 2018. The exercise cost R15 million.

Related article:

Moerane said killings were on the rise because state tenders were being manipulated and exploited by politicians willing to kill for money. He slated the political deployment of ANC cadres in government. South African political parties, he said, needed to build a culture of tolerance and democracy, rather than one of patronage and greed. “The apparently never-ending murder of politicians in KwaZulu-Natal is a symptom of serious pathology in the province’s body politic,” he said. I interviewed Moerane in 2019, and he winced when recalling his experiences in heading the commission. Listening to the testimony was plain dreadful for him. “Some of the stories we heard were blood-curdling. The story of the teacher, Vusumuzi Ntombela, who was shot in broad daylight in Nquthu, in front of his pupils, was devastating. The killer didn’t even attempt to disguise himself. Imagine what that must have done to those children, to see their teacher and one of their peers shot in cold blood.” Moerane is former president Thabo Mbeki’s first cousin. In the 1980s he successfully defended ANC operatives who bombed the Wild Coast Sun, and saved two from the gallows. His lineage and background suggest ANC sympathies. But his criticism of the party was cutting. The violence in KwaZulu-Natal demonstrated the “depravity to which human beings can descend … to murder another human being for material gain”. The culture in the ANC today, he said, is the antithesis of that created by the likes of Nelson Mandela, Govan Mbeki and Joe Slovo. Today’s venal politicians couldn’t be more distant from yesterday’s freedom fighters.

The noted sociologist Professor Paulus Zulu gave controversial testimony to the commission, suggesting that most local councillors were not skilled or morally qualified to hold the positions they do. Some people who wouldn’t qualify for jobs as labourers were earning R15 000 a month as councillors. They immediately adjusted their lifestyle and thereafter clung to their jobs, come what may.

Related article:

Without scruple, they would ensure that nothing prejudiced their livelihood. In his report Moerane quoted Zulu’s testimony about how politicians, like greedy taxi bosses, moved to eliminate opposition. The “culture of blood” required serious study, Zulu said. He pointed out that there were about 400 MPs countrywide, 80 MPLs in KwaZulu-Natal and more than 200 councillors in Durban alone. Competition, he said, was fierce at the bottom of the pyramid. “One either has the job or nothing at all. In the absence of qualifications, negative competition in the form of violence is the perfect recipe,” Zulu said. Zulu compared the remuneration packages of politicians in Australia, India, the United Kingdom, Canada and South Africa, and found the South Africans to be inordinately high. Extra money is derived from the tender system, corruption and kickbacks. As Breyten Breytenbach once described it, “public office is an exercise in scavenging”. Corruption is the backbone of South African politics, Moerane said. “And that’s the cause of violence.” One solution to the corruption was to shine a spotlight on state tenders and publicise who benefits from the business. In addition, effective policing could deal with the culture of impunity. In practice the ruling party had begun to address the issues of corruption and murder but, morally speaking, Moerane felt, “I’m not sure if that responsibility has been taken.” The ruling party might distance itself from the violence, but the elephant in the room was that ANC members were killing one another. One ANC politician did, rather bravely, admit the party’s liability in respect of violence in testimony before the commission. Current cabinet minister and former ANC chairman in KwaZulu-Natal, Senzo Mchunu, was reported on TimesLive as saying: “The ANC must accept responsibility‚ that’s the first thing we need to do. We are responsible‚ whether directly or indirectly. When we accept this responsibility as an organisation‚ we have to act accordingly. I don’t think we have a choice. Somebody said to me the difference between KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo is that in Limpopo when they resolve problems they use muti; in KwaZulu-Natal you kill directly.”

In our interview Moerane said to me that the government had accepted and acted on some of the commission’s recommendations by establishing a multidisciplinary task team with input from the departments of Defence, Safety and Security, and others. Police had started to delve into old murders, and arrests and prosecutions had been made. But he expected more of the police, who often didn’t follow up on leads or complete their investigations. Their evidence showed police incompetence and political manipulation. Moerane described as “disturbing” that Crime Intelligence was “completely ineffectual in providing useful data to stop crime”. Some policemen provided lame excuses to the commission, and on the whole the generals in the SAPS didn’t appear to have a handle on violence at a macro-level: there was no cross-referencing of cases or investigations into the proliferation of high-calibre weapons. “Crime Intelligence is failing and SAPS can’t defend itself against this criticism. That’s damning.”

The private security industry in South Africa is bigger than SAPS, but attempts to monitor it seemed wanting. “It is a startling fact that all types of weapons are in circulation and it is not effectively controlled. Videos are circulated on social media of trigger-happy bodyguards firing their guns into the air, apparently with impunity. And the need for security (as determined by politicians) is self-generated.”

Related article:

I asked Moerane what would give him comfort. He said: to see political murders properly investigated by a professional and efficient police service that would act without fear, favour or prejudice. “So those suspected of murder are prosecuted by well-trained prosecutors. If they are found guilty of murder, they should serve lengthy sentences. Investigations should be thorough and nobody should be spared. The police should go where the evidence leads them, irrespective of who is involved. By SAPS I mean the entire police service, from foot soldiers to the intelligence units.

“There seems glaring evidence of who is responsible for some murders. The police should not be deterred by the status or station of the suspects.

“If you see people being held to account by the judicial system, then you deal with the culture of impunity. Cases must be thoroughly investigated, and they can use the evidence put before the commission as a start. If they do this, they might be able to crack some of the cases. That would inspire public confidence and help change the culture of politics.”

Effective change, he said, required upsetting the “lines of patronage”. “The state must also take measures to immediately enforce the separation of powers, duties and functions between public representatives and officials, and hold each accountable professionally and criminally for their respective conduct.”

The culture of “might is right” that has developed in KwaZulu-Natal has the potential to become the province’s most shameful export. “The evidence presented before this commission is not confined just to KwaZulu-Natal but has similarities with incidents of the murder of politicians in other provinces, and the underlying causes of the murder of politicians are potentially present in all provinces.”

Moerane recommended that the national cabinet study his report. “The culture of impunity and the network of patronage do not stop provincially. It stretches nationally. The problem must, therefore, be prioritised provincially but eventually addressed nationally.”

In 2019, almost a year after his report was submitted, Moerane let out a sad sigh. Will things change? Who knows. He quoted an ANC stalwart from Pongola, a man by the name of Nqaba Mkhwanazi, an ANC councillor, who suggested to the commission that the only way to stop political killings would be for his beloved ANC to lose at the polls. Maybe then the killings would stop, “because there will be nothing left” to fight over, Mkhwanazi said.