New Books | Women Rising

During the 2011 Arab Spring in Yemen, women used social media to direct the protests that led to the ousting of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had been in power for over 30 years.

Author:

15 July 2020

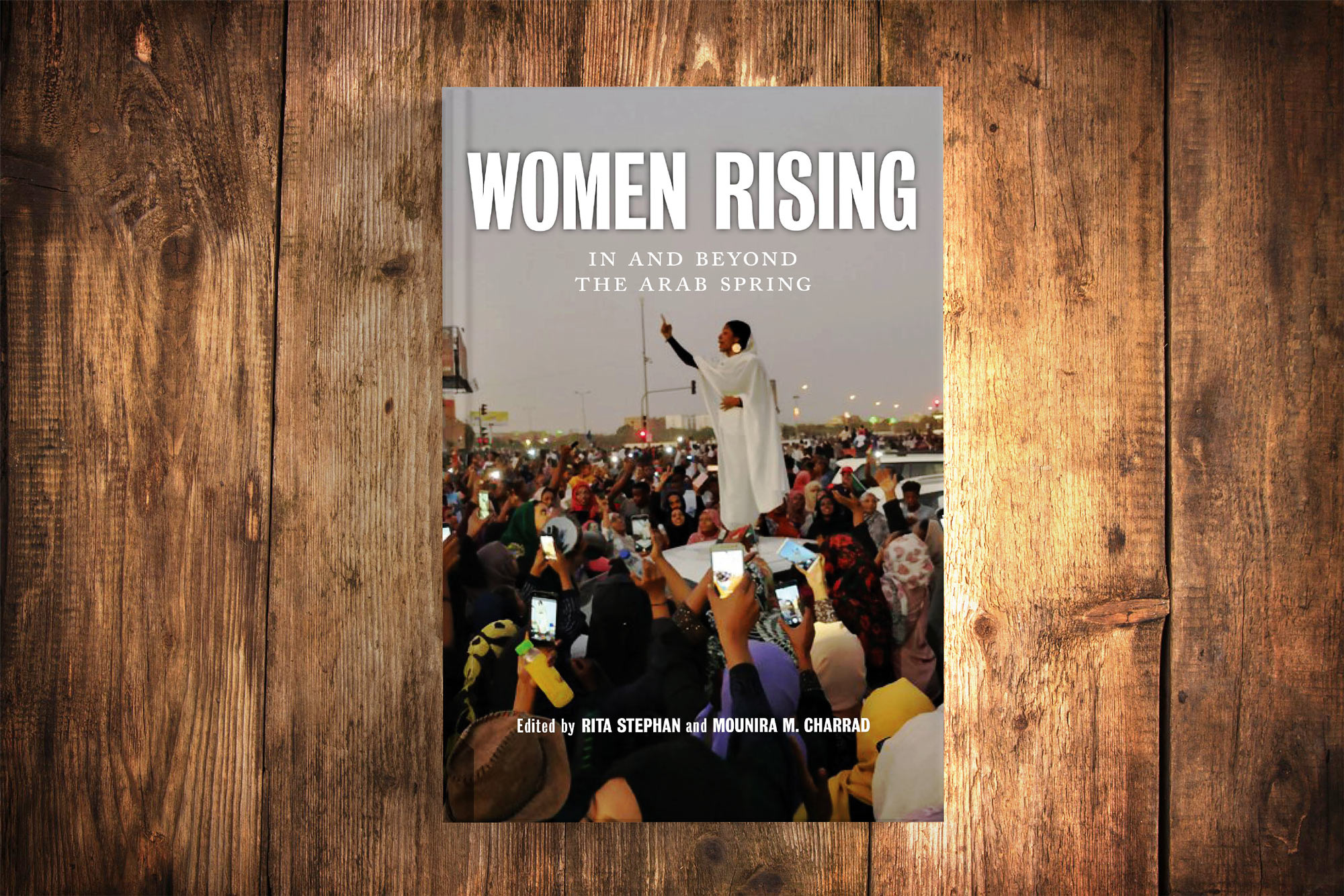

This is a lightly edited excerpt from Women Rising: In and Beyond the Arab Spring (New York University Press, 2020) edited by Rita Stephan and Mounira M Charrad.

Refusing the Backseat: Women as Drivers of the Yemeni Uprisings

“The people want the fall of the regime” is a slogan that reverberated throughout the Arab Spring uprisings, demanding freedom, economic equality and democracy. As seen in video footage, photos, news reports and eyewitness accounts, women were frontline drivers of the uprisings that swept across Yemen. The term “driver” indicates that women pushed, directed and guided the protests with vigorous determination. They were key organisers and leaders from the onset of the protests and throughout their duration.

This chapter assesses the extent to which women drove Yemen’s uprisings, by highlighting the contributions of four women: Tawakkol Karman, Afrah Nasser, Atiaf Alwazir and Rasha Jarhum. It explores the role that these women played as drivers of the uprisings by examining how they initiated, organised and led protests as well as how they managed communications and social media campaigns throughout these protests.

Related article:

Women’s participation in the Yemeni uprisings is important for three reasons. First, women used the opportunity to combine their growing intolerance of women’s rights violations with that of socioeconomic inequalities – two issues at the forefront of the global development agenda. Second, women’s activism in these protests challenged misconceptions about Arab women’s perceived political apathy. This examination of women’s activism contributes to defining women’s framing of their political participation during civil unrest. Third, analyses of the methods and impact of women’s protest have been limited, particularly in an Arab context. Therefore, conclusions from this analysis provide insight into the nature of Arab women’s participation in political protests. I focus on individual women rather than drawing broad conclusions about women as a social group, and I examine women as a segment of society that participated in protests, without reflecting on the level of engagement of Yemeni women in general. I employ a qualitative approach primarily focusing on the first year of the Yemeni uprisings, between January 2011 and January 2012. I use primary documents as the basis of this study, but include interviews and social media venues such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and blogs.

Women in Yemen before the uprisings

Globally, Yemen has one of the highest population growth rates and is among the most food insecure. In 2009, a staggering 42% of Yemenis lived below the poverty line. Health, reproductive issues and lack of education are among the biggest challenges that Yemeni women face. Because schools are often inaccessible and have a mixed-gender setting, many girls are not allowed to attend school because of Yemeni society’s traditional views on gender segregation. As a result of widespread early child marriage, many young women are stripped of educational opportunities and drop out of school early. In fact, two out of every three Yemeni women remain illiterate. According to the Global Gender Gap Index, Yemen’s female adult unemployment rate in 2012 was 41%, one of the highest worldwide. While women can work, societal norms have led to weaker female economic participation. Yemeni women are disenfranchised by their economic dependence, societal status and low levels of education.

Women’s political presence in Yemen mirrors their disenfranchised societal status. Though women received the right to vote in 1967, only 61% exercised that right in 2006, and fewer have run for political office. According to the United Nations’ assessment of Yemen’s progress towards the 2015 Millennium Development Goals, women’s political membership is “very low” and “deteriorating”. In 1990, only four women were in Parliament, with only one in 2000 and zero since 2010. In contrast, women voters increased from 15% in 1993 to 61% in the parliamentary election of 2006. This increase suggests that while women’s representation in Parliament is limited, their desire to be political participants through voting and activism has increased.

Civil society has offered a platform for Yemeni women to be politically active, despite the limitations they face. The first, and most prominent, women’s organisation in Yemen is the General Union of Yemeni Women. It was created in the 1940s and 1950s by the British, and later taken over by women from middle-class families. Approximately 200 women’s NGOs exist throughout the 19 Yemeni governorates, ranging in specialisation from service and charity to advocacy.

Yemen’s civil society operates in an illiberal and restrictive political environment. Because freedom of speech and assembly are highly repressed, Yemen scores low on the civil liberties scale. Political activism, and women’s political participation in particular, were greater during the revolutionary struggle for independence from the British mandate in 1967. However, women have not been involved in many large-scale revolutionary protests since then, with the exception of smaller-scale human rights and free-speech protests that were organised throughout the first decade of the 21st century, which had minimal impact.

Related article:

Technological penetration in Yemen is equally low, especially internet connectivity. In 2010, Yemen’s internet connection rate was among the lowest in the Arab world at 1.8% for Yemen’s population of 23 495 361. Nonetheless, activists in the uprisings did not spare any tech-based mobilisation efforts. Protesters used Facebook, Twitter and cell phone-generated SMS messages to network, disseminate protest information and circumvent the connectivity problem. In fact, mobile users received tweets directly through SMS, utilising a service offered by Twitter for times when users were disconnected.

Women’s political activism until the 2011 uprisings was restricted by social norms and repressive political discourses, which aimed at keeping women confined to the private sphere. While previously championing women’s rights, former president Ali Abdullah Saleh attempted to garner support from traditional tribal leaders to deter women from protesting, by accusing them of “mingling with men” during the protests. Despite his stance, women and other protesters managed to depose President Saleh, who had been in power for over 30 years. After a year of protests, his vice president, Abd Rabbuh Mansur Al-Hadi, served as interim president until the 2014 elections. However, the struggle for women’s rights had just begun.

Women as drivers for the Yemeni uprising

The Yemeni uprisings began on 16 January 2011, and continued until 27 February 2012. The first protests were initiated by female protesters and were advanced by women’s leadership and activism. One of the unique features of Yemen’s uprisings was that media coverage focused on women’s mobilisation and their organisation into women-only protests. Despite their poor socioeconomic status and low political participation, Yemeni women were vivid examples of women’s indispensable leadership role.

Khaled Fattah of Lund University argues that “in Taghir [‘Change’] Square, women were among the most energetic participants in the protests”. In his analysis of what he calls Yemen’s “social intifada” (uprising), Fattah asserts that “for the first time in decades, there was mixed, public interaction between men and women”, making the breaking of gender barriers one of the most impressive achievements of the protests. Through the analysis of female protesters presented in this chapter, it is clear that Yemeni women not only supported and sustained the protests but also initiated and drove the popular uprisings, keeping them alive for a year.

The igniting activism of Tawakkol Karman

Described as the “mother” and “face” of the revolution, Tawakkol Karman is widely recognised as an icon of resistance and change. In 2005, Karman founded Women Journalists without Chains (WJWC), a human rights organisation that focuses on democratic rights and freedom of expression. Prior to the peaceful protests that WJWC held from 2007 until the uprisings, Karman held weekly protests at the Girl’s College of Sana’a University. She was the first to camp in protest in Yemen’s Taghir Square in 2011 but was arrested and imprisoned shortly after. As a result, approximately 200 female supporters gathered and demanded her release. This incident was key to the uprisings and was one of the main factors that caused “the tide . . . to turn against Saleh”. The next day, 24 January 2011, Karman was released, and she launched another protest that afternoon.

After her release from prison, Karman called for a “Day of Rage” protest, and over 20 000 people responded in a mass civil uprising on 3 February 2011. Her activism and leadership in initiating the first protest of such magnitude helped ignite and direct the uprising. With nearly 80 000 followers on Twitter (@TawakkolKarman) and 375 000 Facebook followers, Karman was among the leading female figures of the uprisings, and her popularity spread rapidly. Her status granted her the leverage needed to continue her struggle in advocating for peaceful protests, towards the ultimate goal of democracy. She became an icon of the uprisings as her photo was displayed throughout the protests, in tents and even held and hailed by men. This is especially remarkable in Yemen, as photos of women are not usually displayed publicly. Karman is a member of Yemen’s leading opposition party, Al-Islah, making her an influential yet controversial political figure. She succeeded in becoming the youngest person, and first Arab woman, to win the Nobel Peace Prize, an achievement that gained rapid and widespread international recognition. In addition to her responsibilities as a mother of three, Karman remained firm in her protest activism and celebrated her Nobel Prize in Taghir Square, where she received congratulatory visits in her tent.

Related article:

Time magazine named her one of history’s 16 most rebellious women, an accolade that attested to her courage and leadership. According to Abubakr Al-Shamahi, a British-Yemeni journalist, Karman was integral to the Yemeni protest movement: “In all honesty, the Yemeni protest movement that we see today would not be the same without Tawakkol Karman. Throughout the nine months of the ongoing Yemeni uprising it has become normal to walk through Change Square and hear her voice over the loudspeaker, leading the youth in chants.”

Karman gained international attention as a result of her activism: she met with former US secretary of state Hillary Clinton and UN secretary general Ban Ki-Moon and travelled to New York, lobbying various actors to support the uprising. In a message of congratulations for the Nobel Prize from former secretary of state Hillary Clinton, Karman was praised as a shining example of the difference that women can make and the progress they can help achieve. Clinton and First Lady Michelle Obama honoured Karman with the International Women of Courage Award. In her meeting with Ki-Moon in October 2011, Karman discussed human rights, the dire situation of Yemenis amidst the uprisings and how peace and political stability can be achieved. She shared with him her belief that her Nobel peace award would help accelerate the revolution and garner more support and protesters. Karman was right, as she was celebrated across Yemen and was recognised by prominent celebrities, news anchors and human rights organisations for her Nobel Prize and for her leadership. By initiating the first protests, leading and mobilising protests, and using social media to garner support, Karman became one of the most prominent leaders of Yemen’s uprisings.