New life for seminal sounds of The Beaters and Harari

Reissue of their two records from the 1970s allows listeners to experience the searching spirit that inspired their pan-African identity at a time of apartheid ethnic separation.

Author:

18 March 2021

On a drizzly Saturday morning at Mamelodi Stadium in 1975, the Harari Music Festival kicked off with a line-up of top jazz bands. The headline act was The Beaters, who had recently released the hit song Harari, for which the festival was named. Thousands packed the stadium anticipating The Beaters’ performance. But though the flamboyantly dressed band did go on stage, no music would be played that day and things would soon take a devastating turn.

Because of the rain and an accidental disturbance of electric cables, the electricity was cut off. The band could not be heard and their performance was ruined. The crowd grew angry and, with communication lost, pandemonium broke out. Impatient fans, unaware of the power cut, threw beer bottles and stones at members of the audience obstructing their view of the stage. There was further confusion as some thought The Beaters were being attacked for not performing. A riot ensued and the police were called, shooting some attendees.

The events left an indelible mark on The Beaters as the band would be unfairly blamed for all the chaos. In separate interviews, drummer Sipho “Hotstix” Mabuse and bassist Om Alec Khaoli recall the day. “The World newspaper’s centre spread had all our ‘afro-headed’ faces with a headline saying these ‘big-headed Harari guys’ are responsible for what transpired at the festival,” says Mabuse.

This would also lead to their name change to Harari. “Because of that riot and the big publicity throughout the week saying these are the guys that caused problems, people would look at us and say, ‘Yah, that’s Harari!” And they called us Harari, so that’s how we became Harari,” Khaoli explains.

But while their name is rooted in this moment, which formed part of a tumultuous era, it also signals more: it speaks to the band they became – one that was deeply rooted in a pan-African politics and thought seriously about what it means to be African.

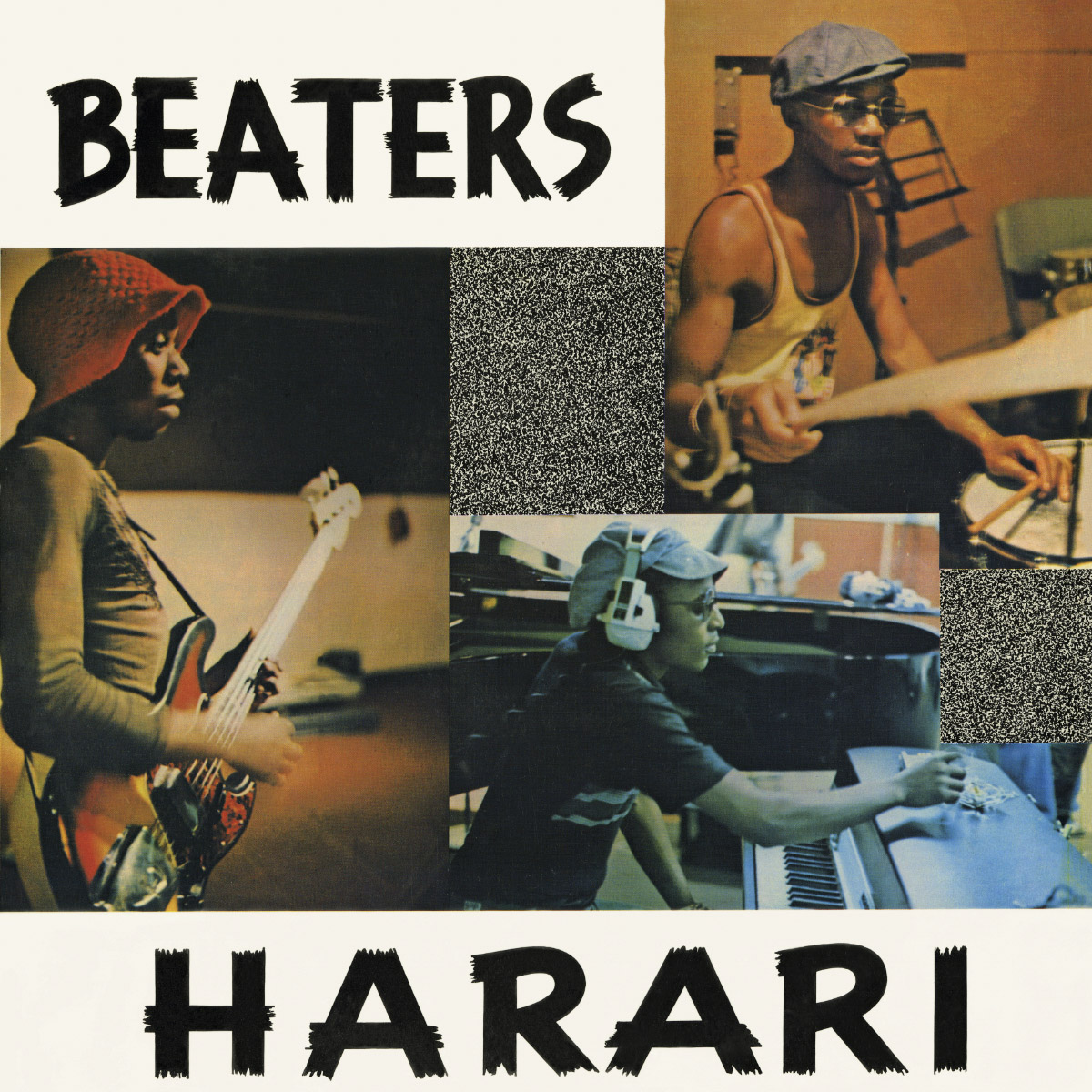

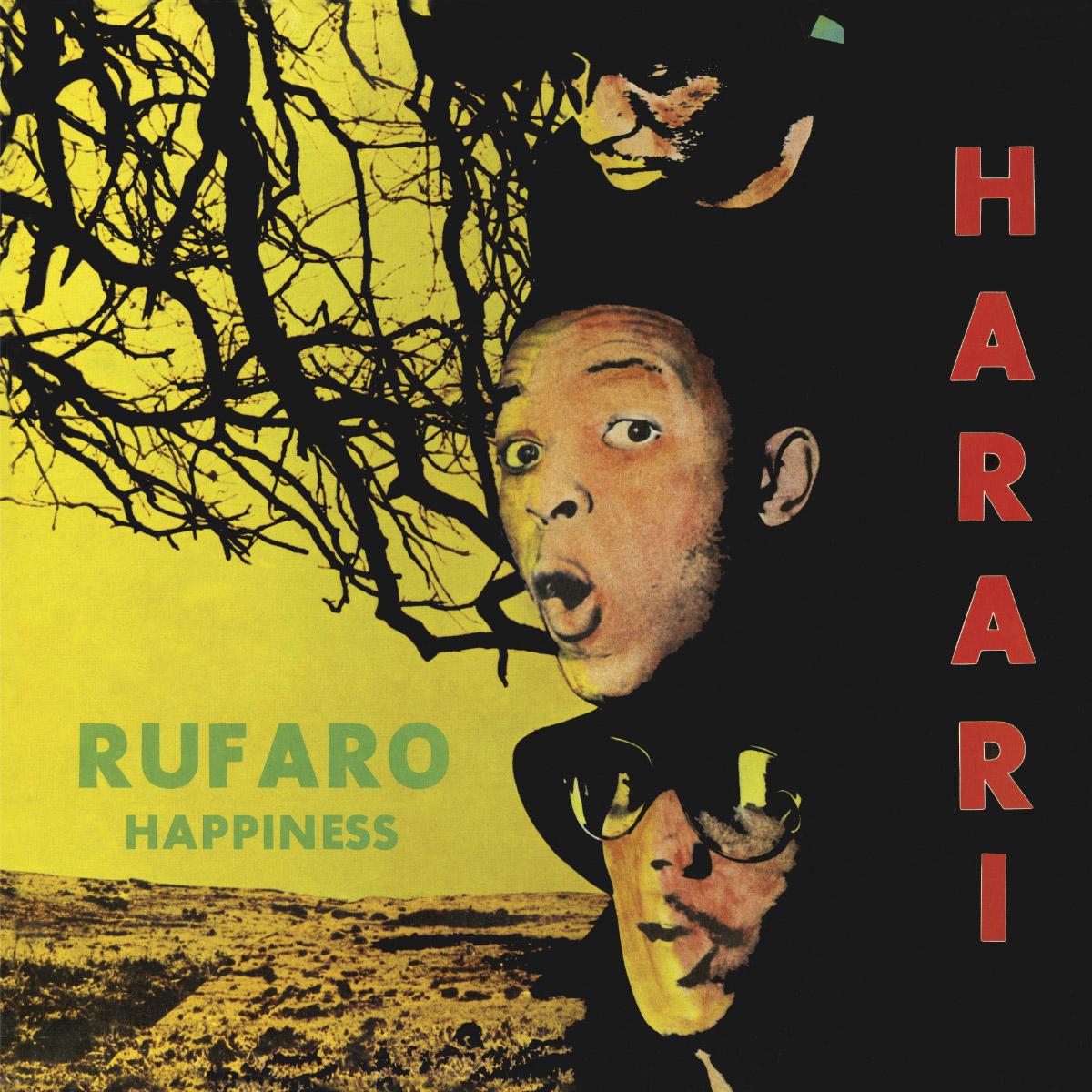

Record label Matsuli Music has now reissued on vinyl The Beaters’ album Harari (1975) and their subsequent album as Harari, Rufaro/Happiness (1976). “These were sequential recordings marking a watershed in the evolution and outlook of the three core members of the band,” says label partner Chris Albertyn. “We thought it important to reissue, re-expose and remind music lovers [of their significance].” The remastered albums include extensive liner notes by music journalist Gwen Ansell as well as archival photographs.

A political sound war

The Beaters met in the 1960s while attending Orlando West High School in Soweto. Their growth is intertwined with the township’s history. In 1968, Khaoli, guitarist Selby Ntuli, guitarist Monty Ndimande and vocalist Arthur Rafapha were a band in need of a drummer. Mabuse introduced himself to Ntuli, who invited him to join the band, thus completing The Beaters.

The political sound war that defined the times creates the backdrop to their story. Since the 1960s, the SABC enforced racist cultural control in the form of Radio Bantu, transmitting in African languages that divided Black people into ethnic enclaves. It also functioned as a mouthpiece for the apartheid regime.

But the youthful band members sought the diverse popular music of the time instead. “Every Friday afternoon I used to listen to Springbok Radio, recalls Khaoli, “because they’d be playing the hit parade with all the most popular songs. I wouldn’t miss that. On Sunday nights, it would be LM Radio that would play the hits. So that was all we would talk about throughout the week at school.”

Rock, reggae and soul music reached them through LM Radio, broadcast from Mozambique, on which “white music” like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin played on rotation. These sounds had a major impact on the young musicians: their name, coined by Ntuli, was an obvious reference to The Beatles, who were a big sonic influence.

Later, soul records from Motown and Stax from the United States filtered in through travellers to South Africa and would influence their sound as well. The spirit of Black Power coupled with Steve Biko’s Black Consciousness created a new awareness for the youths and Black pride and style were king.

School superheroes

The Beaters’ rise to fame was accidental. Their first gig together was at their high school’s fundraiser, encouraged by their principal. “After that gig, the schoolchildren were very excited about us,” Khaoli says. “They made us superheroes at school the following day and everyone was talking about us. They told their friends at other schools in Soweto, so then those students wanted to have us perform [too].”

Orlando boxing champion Levi “Golden Boy” Madi sponsored the band’s music instruments. Soon they were performing at different high schools and universities and their following grew immensely. Between 1968 and 1969, the Beaters recorded the albums Soul-A-Go-Go, Hot Dogs and Lost Memories. Their sound became known as “Soweto soul”. At the time, they performed in stylish Nehru suits.

Mabuse says Orlando was one of the central points for Black resistance. His parents were members of the ANC and his neighbours supported the PAC. “There was a lot of activism there. That influence would not escape me. It was very tough, but also it was robust. We were always exposed to meetings that were held in our homes, speaking about Albert Luthuli, Oliver Tambo and Ntate Nelson Mandela.”

Another legendary Soweto connection was to Kaizer XI, the original name for football club Kaizer Chiefs, managed by the eccentric Ewert “The Lip” Nene, who lived in their area. “He heard about us and took us on. So Kaizer Chiefs and The Beaters were like one family. We were always together with them as they were starting, even [in] how they got their players together from across South Africa and Namibia,” Khaoli recalls.

Inspired by Zimbabwe

During these formative years, the band toured parts of southern Africa, including the then Rhodesia. They found the political atmosphere of the country as it was nearing independence infectious. “For us, it was just another tour until we got there and realised that the struggle for liberation was intensified in that space,” says Mabuse.

While only intending to stay for three weeks, The Beaters spent three months in Harare, which was still known as Salisbury. “The level of consciousness among the people in Zimbabwe had an influence on how we had to approach our own music,” says Mabuse. “Zimbabwe was on fire for us. And we realised we cannot be seen in isolation of what was happening there.”

Related article:

So it was in Zimbabwe that The Beaters reached an awareness of African identity and unity and embraced a spirit of pan-Africanism. It was also where they discovered music from the rest of the continent for the first time, which would shift their sound.

“Musically, our influence became very African because we felt we should build that sense of pride,” says Khaoli, adding that they “internationalised the sound instead of tribalising it”.

Mabuse adds, “For us, it was to create music we could relate to the struggle of our people. Let’s be real about who we are. Black Consciousness influenced our thinking greatly during that period.”

Returning home inspired, they recorded the album Harari under the guidance of Rashid Vally from As-Shams, which was one of the only Black-run labels at the time and known for its great jazz releases. Through Vally’s jazz connections, artists such as saxophonists Duke Makasi and Barney Rachabane and trumpeters Stompie Manana and Dennis Mpali were invited to join the session.

Related article:

In studio, The Beaters serendipitously encountered the jazz saxophonist Kippie Moeketsi, who later invited Mabuse and Khaoli to join him, Basil Coetzee and Pat Matshikiza on the album Tshona! As mentors, these “elders” passed on their knowledge and encouraged the younger musicians to continue their mission. “Their contribution was quite immense because suddenly our music took on a different direction as a result,” says Mabuse.

About Vally, he says, “He was always willing to open his doors for new music and ideas, which most record companies were not willing to do… Most of the music would not have been recorded elsewhere if Rashid had not intervened in that way.”

Adds Khaoli, “I remember at his record store Kohinoor, in Kort Street in downtown Joburg, on Saturday you would find people from all over the entire Transvaal [Gauteng] area converging there. He was the one getting all the best artists and people would go through all those records. Just being in the shop was such an atmosphere itself. People would converge there and have their pap and steak around there, drinking and enjoying listening to music.”

Defying categorisation

Harari was a hit. The band were able to encode the message of their music so that it came across as palatable pop music that could be played on radio. The title track was deliberately sung in Shona. “We would even choose to sing in a language that is foreign because we knew the SABC wouldn’t be able to categorise it. That was one thing that helped us to cross over to many people,” says Khaoli.

A year later, in October 1976 and following their name change, Harari’s follow-up album Rufaro/Happiness was recorded and released. The stadium events that indirectly led to their new name reflected the tension that was brewing in the 1970s, when riots and a police presence were commonplace. The events of the Soweto uprising on 16 June when schoolchildren were brutally killed by the police had left South Africa shaken.

Guests on the album included Moeketsi and guitarist Themba Mokoena. The band swapped their Nehru suits for dashikis and afros to embody a more African identity. In the process, they created a sound that was labelled all too simply as “Afro-rock” but was really a fusion of funk- and rock-inspired rhythms with African roots.

Related article:

As the title suggests, with rufaro being the Shona word for happiness, the focus was on creating happy, joyful music. “We were trying to bring smiles to people’s faces,” Khaoli says, “because it was just so depressing to see what was happening. And instead of focusing on their problems, we thought let there be peace and love. In our rhythms, we wanted happy music to lighten the people’s hearts. And people really loved us for this.”

Their popularity led to an invitation from Hugh Masekela in 1978 to join him on a US tour. However, while finalising their plans, the band received shattering news: Ntuli had died suddenly in his sleep at the age of 28. “He influenced us all. As a performer, Selby would do amazing things on stage. He would play as if he was possessed and he would be in his own world,” says Khaoli.

Reflecting on the magic they created on stage, he says, “Harari was just like one unit. As a band, we were so united spiritually that often things didn’t need to be said, they would just happen. There was just so much power in the whole thing. We would rehearse briefly and perform the show. And when we performed, we got something out of ourselves that we didn’t even know we had, because it was something spiritual.”

About the two records finding new life, Mabuse says, “I’m elated and I’m beside myself. I’d never imagine they would be coming out.”

Khaoli agrees, “We are fortunate because now that we are older, we get to see these records still moving and happening. People will have an opportunity to go back in time and experience what we were going through.”