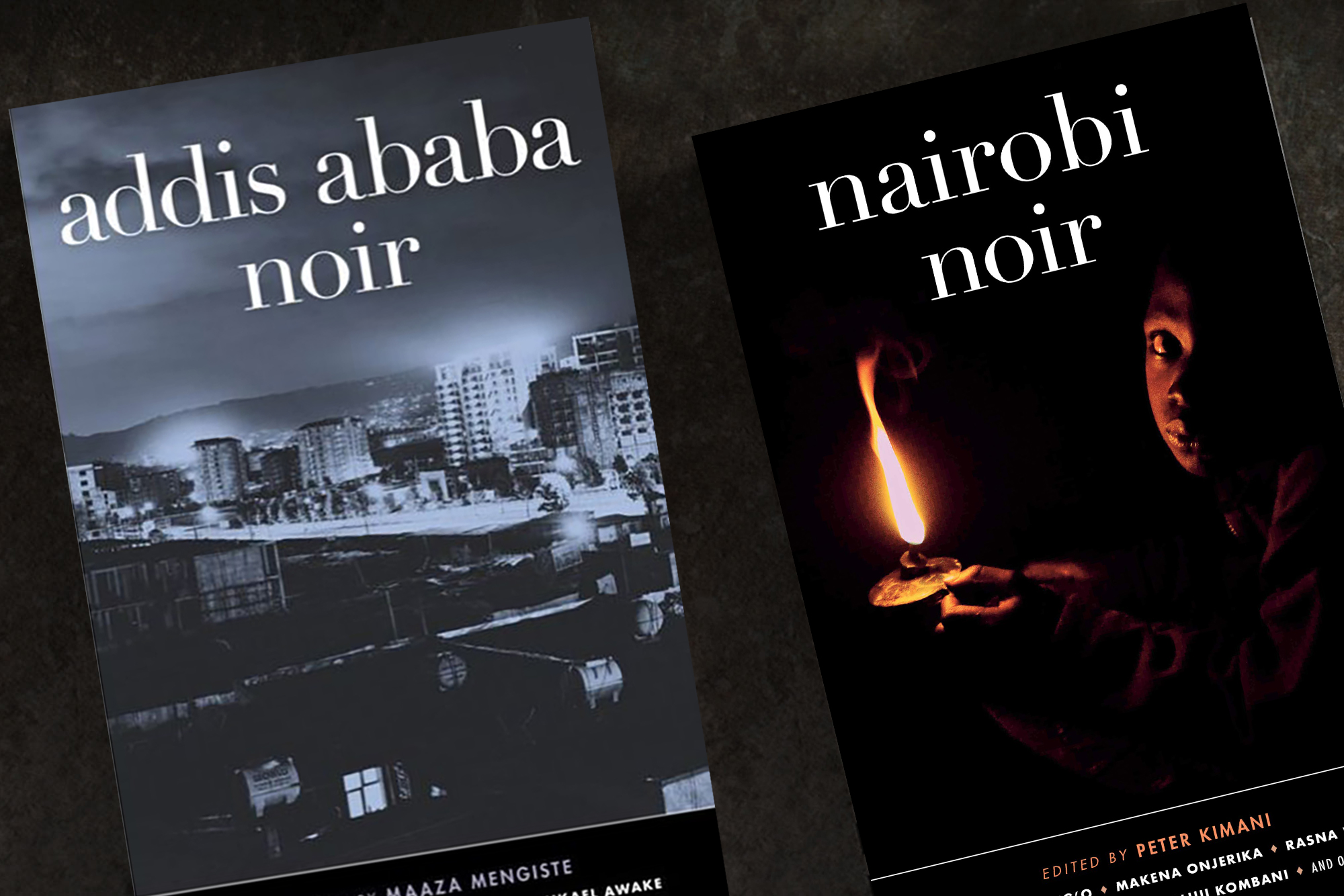

Noir books depict East African cities

Two new short-story collections explore the darkness, disorder and chaos of Nairobi and Addis Ababa, as writers attempt to portray the haunting underbelly of those vibrant cities.

Author:

15 September 2020

At the turn of the millennium, the Brooklyn-based indie press Akashic Books started a noir book series that has since racked up popularity and big names with over a hundred fiction collections from all over the globe. Though focused mainly on American places and themes, Akashic has also rolled out international titles over the years. This year, two noir anthologies from the brilliantly dynamic cities of Nairobi and Addis Ababa have been published within months of each other.

Noir is about indulging the dark side. And both Nairobi Noir and Addis Ababa Noir take the directive to narrate this darkness seriously. What emerges is a portrait of two East African cities crushed under the weight of economic hardship, failed hustles, battles with the ghosts of recent pasts, and rigged systems.

Related article:

I learned about this series when assigning several stories from many of Akashic’s Noir volumes for a class on postcolonial crime – the only class I’ve ever taught that was filled past maximum capacity and with a majority of male students. As a genre, crime is perceived as phallic, erect, sexy and thrilling, I had irritably understood, and perhaps inadvertently made it my mission to disappoint this group. The class focused more on noir writing, an antidote to fantasies of virility and a genre that demands a certain intellectual rigour and a capacity to cope with lack of closure.

The series’ commitment to a world literature united by pessimism and despair is admirable. Particularly, in our times of the plague, where most of us are battling darkness, unease, isolation, perhaps hopelessness, reading two noirs back-to-back did hit the spot.

The roots of noir

Melancholic and deliciously negative, noir has roots in cinema and writing, and expresses societal malaise such as corruption, poverty, violence and war through characters who are often cynical, unlucky or depressed. Though it is a cousin of the crime and detective genres, neatly tied-up endings and smug moral lessons are rare.

Almost every city, country or neighborhood has its dysfunctional side, so noir applies universally – there’s no dearth of things to explore, whether it’s Milwaukee, Delhi or Brussels.

The books in this series construct and deconstruct “place” in interesting and unique ways. Often edited by well-known writers (Tayari Jones, Joyce Carol Oates, Edwidge Danticat and Chris Abani, among others), individual books tend to be predicated on a kind of innate loyalty and intimacy alongside despair, frustration and critique of the “place”. To that end, some of these books inadvertently become a volume of national literature. A preoccupation with history, the place of the nation in the world and a multivalent representation of the country can thus be found in both the Nairobi and Addis Ababa volumes.

Related article:

Mengiste’s collection deliberately places Ethiopia at the centre. She wants to peel away the layers of the “storied” history of a complex and ancient country through the ever-evolving and robustly multicultural Addis Ababa. Kimani appears more focused on Nairobi and has divided the book’s stories according to the city’s many neighborhoods. Both carry maps at the beginning, and the centrality of place in noir writing is emphasised. When I attended the launch of Nairobi Noir in Nairobi’s beautiful downtown space of the Alliance Française, there were 10 writers on stage out of the 14 included in the book. The effort being made and the excitement around this unprecedented volume was palpable, and copies sold out right away. When Kimani declares that such a collection “is unprecedented in Kenya’s literary history” and that it “offers an entire spectrum of Kenyan writing”, its national thrust cannot be denied.

Excavating the past as a necessary act

Addis Ababa Noir is a beautiful read, and it succeeds in the historical excavation it undertakes. Divided into “Past Hauntings”, “Translations of Grief”, “Madness Descends” and “Police and Thieves”, the first three sections engage the turbulent and violent 1970s and 1980s, and their traumatic aftermaths for Ethiopia. Mengiste’s own story, Dust, Ash, Flight, emerges from the real-life forensics team that went from Argentina to Ethiopia to find the murdered and disappeared victims of death squads. Digging into the country’s past is not only a metaphor. Excavation is a fraught and necessary act.

Stories by Meron Hadero, Hannah Giorgis and Rebecca Fisseha are heartrending accounts of return as members of the Ethiopian diaspora grapple with their own as well as intergenerationally transmitted traumas. Phantoms and hauntings are very real in this collection, and there are a surprising number of brilliant ghost stories. Noir beautifully blurs into horror here. The blue shadow of a woman follows her living son around as he seeks to solve the mystery of her untimely death in Mahtem Shiferraw’s poetic story. And subverting mainstream understandings of the Ethiopian adoption import industry is the story by Mikael Awake called Father Bread. Bloodcurdling and brilliant, it involves humans who can shapeshift into hyenas. Equally hair-raising is Eritrean-Ethiopian Sulaiman Addonia’s devastating story about a man who answers an ad to be sexually dominated for an evening.

Mengiste told me that she brought together Ethiopian writers who lived in Addis and beyond, as well as those who were part of the diaspora. She was also keen to include translated works, given the language diversity in Ethiopia. All of them, however, were united in their ease with writing noir. After all, Mengiste explains, “noir exposes the disorder of society” and for these writers, narrating the ghosts and dystopias came naturally.

Related article:

With haunting comes madness, and the “Madness Descends” section is equally tantalising, with stories that want to erase the lines between the real and the imaginary, normality and madness, truths and lies. Lelissa Girma’s insomniac has forgotten how to sleep. Readers spend a bleary-eyed three and a half hours with him, which devolve into shocking revelations. The mad poet in Girma T Fantaye’s story runs from shop to shop and person to person asking what happened to the cafe he frequents. Could the city have changed that much or has the city entirely changed him?

In Bewketu Seyoum’s tragicomic minibus vignette, a university student’s attempts to flirt with a young woman are cut short when he is confused by the mention of Angelina Jolie. “The institution where he was spending four years was a place of knowledge. Yet he did not even know who Angelia Jolie was.” There is nothing like a ride in a local minibus to understand what Mengiste calls “the lapsed realities that hover just above the Addis that everyone else sees”. The final “Police and Thieves” section is slightly more conventionally noir. There is less of the paranormal here, but the stories are tightly written and just as compelling.

“These are not gentle stories,” Mengiste writes in her introduction. “They cross into forbidden territories and traverse the damaged terrain of the human heart.”

The stories can be jarring and difficult, but how else can a complex, unwieldy and rapidly transforming post-conflict society be narrated? The collection subverts our romance with cities as it unveils a palimpsest of cruelty, deprivation, broken hearts and ghosts. Addis Ababa Noir is a powerful collection, carefully curated and plunging unexpected depths.

A turn to preservation

Unlike Addis Ababa Noir, the Nairobi Noir collection wishes to preserve the old Nairobi and reads more like a nostalgic homage than an incisive archaeology. Kimani writes that the collection will allow future generations to rediscover “the city’s ossified past” that is now buried under layers of construction as entire neighborhoods get remodelled into apartment or office blocks to accommodate an ever-growing middle class. Harking back to Nairobi’s sylvan history, the book is divided into “The Hunters”, “The Hunted” and “The Herders”.

The depiction of Nairobi’s inequality and the hardships experienced by the impoverished is the subject of many of the stories in the collection. In the first section, Troy Onyango’s story is a poetic stream-of-consciousness narration from the perspective of a destitute addict lying amid the bustling anonymity of Tom Mboya Street. Memories come and go and reality gets more blurry with each passing minute. Kevin Mwachiro’s Number Sita is a literal trip down memory lane. Told through the perspective of a taxi driver, the reader is able to ride along through the city. The journey homes in on Number Sita, the place of the narrator’s and his friends’ adolescent memories and their sexual and emotional awakenings.

The second section tends to focus on encounters between the rich and the impoverished, through sex and employment. People are hustling to move up in life, to change the station assigned to them. Cops and robbers frequent the pages, while the lines between the hunters and hunted, the victims and the victimisers are slowly and deliberately erased in the stories.

Related article:

Ultimately, the goal of the collection is to narrate poverty, and while it succeeds in saturating the book with that theme, there are also absences. Recently, the death of Kenya’s longest-serving president, Daniel Arap Moi, stirred up a belligerent and complicated debate over Moi’s legacy. Reading Addis Ababa Noir’s focus on the fear-laden, violent legacy of the Derg regime made it hard not to wonder why there was no exploration of that long, dark era in Kenya’s history.

I was also uneasy about how the collection treated Somalis, one of the oldest and most populous groups residing in Kenya. Winfred Kiunga’s She Dug Two Graves is a gritty tale set in Eastleigh and told through the eyes of Somali refugee characters predicated around the themes of murder, revenge, torture, corrupt police and Kenyan xenophobia. The story is immensely sympathetic to and invested in defending Somalis but it comes off very forced. It tediously works through all the stereotypical elements associated with Somalis such as female genital mutilation, camels, terrorism and Al-Shabaab, and also makes gratuitous religious references. Somalis show up in other stories too, and while Nairobi Noir is indeed haunted by Somalis, not a single Somali writer is included. This is surprising given the large number of Somali writers who live and work in Nairobi.

Rasna Warah’s brilliant story Have Another Roti almost makes up for these critiques of the collection. Told from the perspective of Anamika, who belongs to a well-off Asian family in Kenya, the story is about Anamika’s attempts to heal from the loss of her Somali lover, Raage. Warah has written critically about the United Nations and the humanitarian saviour complex in Kenya. So it is exciting to get a piercing, inside look through her fiction into the personal dramas of employees of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees. More importantly, we are invited into the world of the heavily enclaved Indians in Kenya, their segregated lifestyles and often racist mindsets. Given the story’s effortless literary style, one hopes Warah will turn it into a novel.

Despite being somewhat uneven, this is a successful collection, which brings together a truly distinct set of new and old voices. Calling Nairobi layered is an understatement, and this collection starts peeling back the surface by attempting to harness the volatile energies of a complicated city that hides more than it reveals.

A question of audiences

On reading the two books, one does wonder about their target audience. Are they for a Western audience to soak up a little Africa? Are they for the reading public in Nairobi and Addis Ababa who wish to see their lives mirrored in the stories? (Certainly, it seemed that way at the Nairobi launch.) Are they for instructors of postcolonial literature? Perhaps, they are for all of the above.

Talking to Mengiste, it seems these collections are for the writers too. Mengiste admits to revelling in befriending new talent and building a community of writers while working on the anthology. “I wanted a bridge,” she says. “I want these talented Ethiopian writers to be better known.” But she doesn’t want to import their talent to the United States. Rather, she hopes they will be better known in Africa. “When the book is sold at Ake Festival or the Hargeysa International Book Fair, or any African literature festival like that, these writers will start to be read on the continent.”

Indeed, nothing can be more important to the mammoth and sprawling thing that is African literature than the dreams of fluid literary exchanges and creative circuits.