Reopening eSwatini’s controversial Ngwenya Mine

A licence to restart work at an iron ore opencast mine has been issued despite complaints of poor working conditions and dust and water pollution affecting the surrounding areas.

Author:

20 October 2020

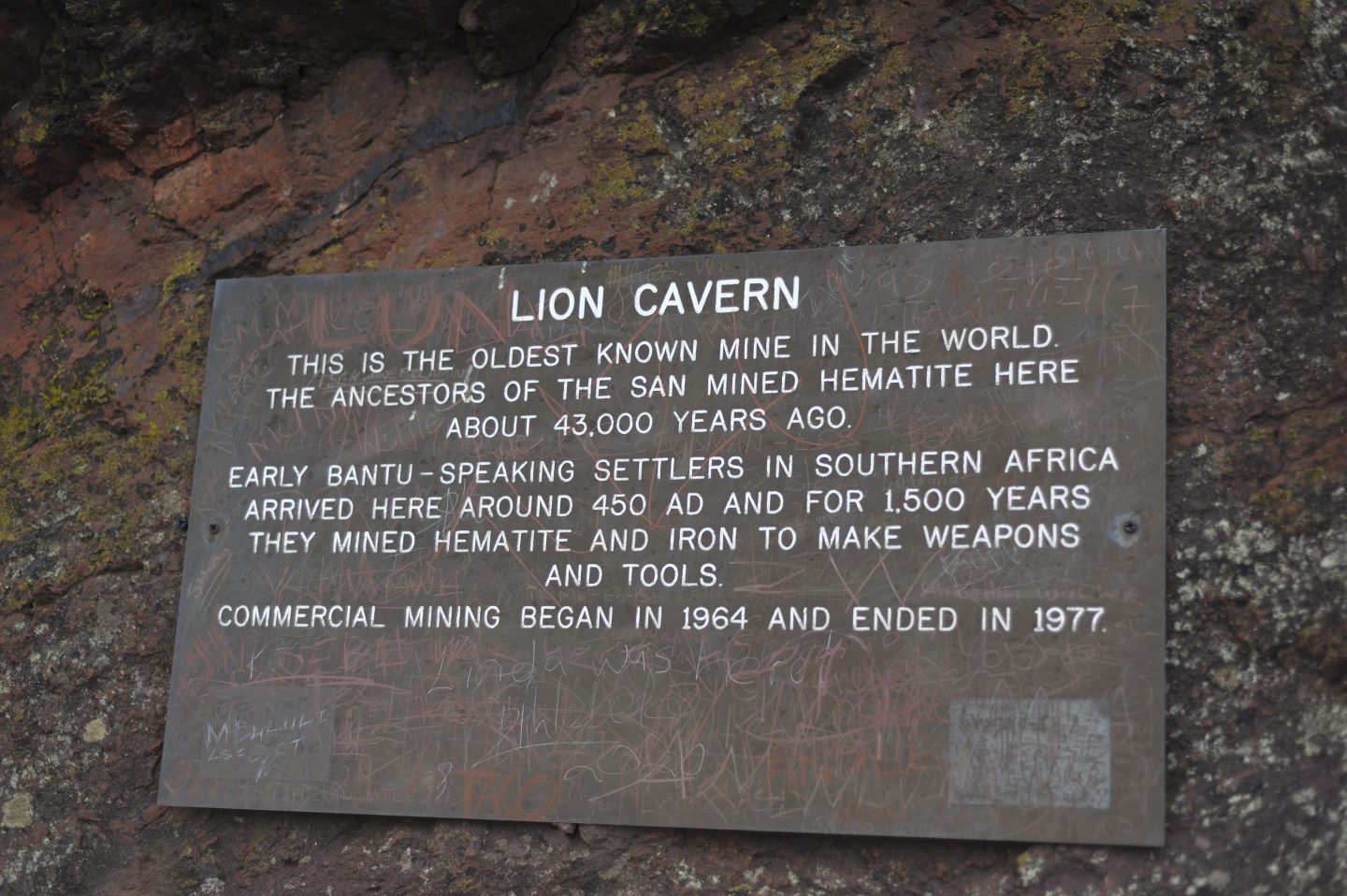

The second-biggest mountain in eSwatini, located in the north-east near the main border gate, is called Ngwenya because, at first glance, it looks like a crocodile. On its crown is a massive man-made crater, and on its side is a small hollow big enough to shelter a pride of lions, called the Lion Cavern.

The hole in the crown is a wound opened by machines a few decades ago. The one on the side is evidence of mining activity from over 43 000 years ago, as the then Bernard Price Institute for Paleontological Research at the University of the Witwatersrand found, making it the oldest known mine in the world.

But Ngwenya Mine is a site of pain for many exploited workers. Liquidated in 2014, the mine is set to reopen again this year, despite dust and water pollution and complaints of corruption and poor working conditions.

Related article:

Lion Cavern makes the mine a tourist attraction. In 2008, the Swaziland National Trust Commission (SNTC) together with the Swaziland National Museum began a process of petitioning the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) to declare the whole mining area a World Heritage Site.

Between 1963 and 1977, the Swaziland Iron Ore Development Company, a subsidiary of the Anglo American Corporation, dug up tons of hematite from the opencast Ngwenya Mine. Hematite is a hard oxide mineral with a high iron content (70%). One and a half million tons were shipped in 1967 alone.

After stopping operations in 1977, Anglo American continued to ship the mountains of ore already dug up and prepared. But it proved too plentiful. In 1979, all operations came to a halt, leaving behind mounds of hematite, mainly in the form of “fines” or small particles.

In this state they remained for many years. Up in the mountains, the main big holes, which were steep and contoured, got invaded by wattle and pine trees. Other plants followed, most of them exotic. Then, in 1982, the old mine became a protected area, falling under the newly established Malolotja Nature Reserve, and administered by the SNTC.

Things changed in 2011. The Mines and Minerals Act was signed into law by the king. The country’s Minerals Management Board granted VM Salgaocar & Bro Pvt Ltd a licence to mine what it called “iron ore dumps”.

Salgaocar then bought some ministers iPads “as a token of appreciation for welcoming the investor to Swaziland”. A controversial environmental impact assessment report was submitted to the eSwatini Environment Authority. A South African company, Fines Mining and Melting (Pty), built three processing plants at the mine. Shortly afterwards, Salgaocar began mining.

Section 133 of the Mines Act states: “The iNgwenyama in trust for the Swazi Nation shall acquire 25% shareholding without any monetary consideration in a large-scale mining project for which a mining licence is granted.” iNgwenyama, in this context, means king. Mswati III, the reigning monarch, raked in the proceeds. The government, likewise, got a 25% share.

“In trust for the Swazi Nation”: not many people in eSwatini know what this phrase means – and there is no evidence of its implicit claim, which suggests everyone should benefit from the country’s natural riches.

Why Salgaocar?

The mining licence granted to Salgaocar was the first given in 20 years. It is not clear if other mining companies applied for licences in the interval, and especially to mine at the Old Ngwenya Mine, or why the company was chosen.

According to City Press, Salgaocar boss Shanmuga Rethenam knew the king way before the licence was granted in 2011, and even before the Mines and Minerals Act was promulgated. In 2010, he sold the king a plane (now his personal jet) for $11.45 million and helped revamp it. This would later be one of the reasons for Rethenam and the king’s relationship souring in 2014, with the mine eventually closing down.

In October 2011, mining – the so-called rehabilitation of tailings – began and went on for three years, abruptly coming to a halt in October 2014 “because of a drop in global iron ore prices”. This is the official story. Some reports suggest that the mine closed because King Mswati and Rethenam’s relationship ended after a dispute about money owed for the refurbishment of the plane.

Related article:

Mukelo Mnisi became an employee at the mine in August of 2012. He, alongside many others, was hired by a labour broker called Gundane and Sons.

Mnisi joined the company as a weighbridge clerk, earning R1 470 a month after deductions. He was later promoted to the position of supervisor. He says the monthly salary was then slightly raised, coming close to R2 000 before deductions.

“We had absolutely no benefits. Not even medical aid. All we had was a small clinic housed in a container in the mine’s grounds and nothing else. What they deducted from our salary was provident fund money. Even that fund money was, at some point, not paid. For three months. Especially towards the end,” says Mnisi.

Sindiso Masuku tells a similar story. He too worked as a weighbridge clerk, from February 2013 till the mine’s closure in 2014. Even though he worked eight hours a day six days a week, he never saw the job as proper employment. “It was something to wake up to, better than staying at home,” he says. “It was more like litoho, a taxing permanent job with piece-job pay.”

Poor working conditions

The majority of employees worked without proper protective clothing – especially those whose tasks involved cleaning vehicles and fixing things. Many, Sindiso says, did not even have gloves and masks. The immediate mining area at Ngwenya gets covered in a thick coat of red dust during operations, even spreading to areas miles away from the mine. Most employees had to work through that, for eight hours a day. There was no drinking water.

Ngwenya is in the highveld, and it gets very cold in winter. No jackets were provided. Workers had to use their own clothing. In the dust, these never lasted long.

There was also the problem of lightning. Due to the high iron content, the area is susceptible to lightning strikes. It is especially bad in summer. Masuku relates what happened one December afternoon. The rain was coming down in torrents, accompanied by thunder and lightning. Yet workers were not allowed to stop. Ore had to be loaded onto trucks and weighbridge employees had to monitor the whole process.

“There was no shelter. Not even raincoats. So, you had to stand in the rain and continue working. A truck would pull out and only then would you have a minute to take shelter under a stationary grader’s moldboard,” says Masuku. “And you could not complain, lest you be fired. There was always a long line of people outside looking for work.”

Muzi Shongwe tells of bad working conditions too. He says when Salgaocar chief executive Sivarama Prasad was present, workers suffered verbal abuse. He would shout about things over which they had no control. Shongwe says he stayed because he had no other choice.

Secretary general of the Amalgamated Trade Union of Swaziland (Atuswa) Wander Mkhonza said that in 2014, the Swaziland Processing, Refining and Allied Workers Union (before algamating to form Atuswa) began a process of organising workers at Ngwenya.

In a statement issued months before the mine closed down, the union expressed concern about working conditions.

“The perpetual violation of workers’ rights by Salgaocar is unbelievable. It is horrifying to note that in Swaziland where we have labour inspectors we can still have a workplace where there are no toilets and drinking water. Workers are exposed to disease as they eat their food before they could even wash their hands because there is no water, yet the bosses are always provided with bottled water.”

Salgaocar stopped operations abruptly in October 2014. Workers were not paid their full salaries. Many of them were given only a fraction of their meagre salaries.

“It was more of a fly-by-night situation. No one told us anything. But there were signs. First, heads of departments left [as if taking leave days off], until there were only a few left. Then some contractors began removing their equipment from the plant. Weeks later, the labour broker that had hired us called a meeting. … He told us that the mine was now closed, and we were no longer allowed inside. He told us there was no money, and we’d get half of our salary. There was no severance pay, nothing. All we would get is only a fraction of our salary,” says Mnisi.

The labour broker, Gundane and Sons, could not be reached for comment.

A long list of contractors were also never paid. It is still not clear if an ongoing liquidation process will pay them out.

Trucks and road accidents

When Anglo American mined at Ngwenya – from 1964 up until 1977 (and in the years from 1977 up until total closure in 1979) – iron ore was transported by trains. The ore descended the mountain into Ka-Dake Station through conveyor belts (after an elaborate beneficiation process). It was then loaded into trains, transported along a 210km railway line from Ngwenya to Maputo (then Lorenzo Marques) and loaded onto ships bound for Japan.

When mining operations resumed in 2011, the ore was transported by trucks. Salgaocar did not revive the railway line. These trucks made an average of 223 trips per day between Ngwenya and Mpaka, travelling on the MR3 Highway, a major route with heavy traffic. In the three years the mine was in operation, nine of the ore-ferrying trucks were directly involved in serious accidents, leaving many people injured or dead and vehicles destroyed.

Six accidents involving iron ore-ferrying trucks happened in a space of three months in 2012 alone. In April 2014, a truck carrying iron ore crashed into vehicles in Malagwane, a dangerous stretch of road along the MR3 Highway just after Mbabane. Two people died, including the truck driver, and many were injured. Twenty-three cars had to be written off.

But that is not the only problem.

The MR3 Highway is in disrepair. On the road’s left lane, from Ngwenya to Mbabane especially, the surface has become uneven in parts, with potholes the size of bathtubs. The road is not yet 15 years old.

Acting chief roads engineer Vusie Mabuza could not be reached for comment.

Water problems

Less than a kilometre from the site of the mine is eSwatini Water Services Corporation’s water treatment plant. Its closeness to the mining area makes it vulnerable to runoff and dust pollution.

Questions about the water issue were sent to eSwatini Water Services Corporation’s public affairs manager Nomahlubi Matiwane. She had not responded by the time of publication.

Water from the Ngwenya treatment plant supplies residents of Ngwenya, Motjane and other areas including Mbabane. The water is drawn from Hawane Dam, a reservoir at the foot of the mine site.

Nomsa Vilakati*, a resident of Ngwenya Village – a settlement built by Anglo American for its employees – says at some point red water came out of house taps. There was also dust everywhere, she says. “You hang your clothes outside and they [go] red from the soil.”

Gary Hayter, general manager at Ngwenya Glass – a 33-year-old glass-blowing factory and tourist attraction near the mining site – says the sections in the environmental audit report about water resources are a joke. He says the whole document was put together to justify the mining company’s actions. It disregards the environment and water sources in the area.

Related article:

Not only did the mining operation lead to pollution of water sources in the area, but it also depleted reserves since the Ngwenya Mountain is a catchment area, says Hayter.

One beneficiation plant is located on a ridge at the mining site. When it rains – which it often does in summer – there is runoff into the Motjane River. There are no sites into which the water can percolate.

A new report by the environmental assessment company R3 Services found that there is contamination in the water bodies around the mine. It singled out the Ngwenya Stream, Malolotja Dam and Ndlotane Stream, saying: “The levels are … within acceptable limits for body contact but not suitable for drinking.”

Despite this, R3 Services prepared an environmental assessment report that greenlights the reopening of the Ngwenya Mine.

Reopening of mine

The Times of eSwatini reported on 25 May 2020 that the mine will reopen. Taking over operations this time is Vuka Lilanga Minerals.

“Vuka Lilanga Minerals Pty Ltd (VLM) is an Eswatini mining company established in the year 2017, focused on iron ore exploration and production in [the] Kingdom of Eswatini (Swaziland). VLM is a subsidiary of SWAGEO Capital and Holdings Ltd, a holding company registered under the laws of United Arab Emirates,” the company website states.

A quick look at the new company’s leadership shows that they are led by the people who were at the helm at Salgaocar. The only difference is that there is now an eSwatini citizen in a top leadership position. Prasad, former Salgaocar chief executive, is the boss of this new company.

No new licence was granted to this “brand new” company. The eSwatini Minerals Management Board simply transferred permission from Salgaocar to Vuka Lilanga Minerals.

“A new approved investor, Vuka Lilanga Minerals was granted the mining licence included a mining lease together with all the necessary statutory permission transferred from SG Iron Ore Mining Pty Ltd to Vuka Lilanga Minerals Pty Ltd in order to resume the operations without any time delays. The liquidator will then clear all the debtors of the SG Iron Ore Mining Pty Ltd from the liquidation proceeds and Vuka Lilanga Minerals Pty Ltd will be free from any liabilities of the previous operator. The past operations liabilities inclusive of environmental liabilities lies with the Liquidator,” reads the environmental audit report.

Residents not consulted

The whole Ngwenya Mine area remains a popular attraction. It is especially popular among eSwatini nationals because of the hashtag #VisitEswatini.

Despite this, a visitor centre that caught fire and burned to the ground in 2018 still has not been rebuilt. There is no refreshment station or working toilets for visitors.

There is no evidence of maintenance work done recently. But the Trust Commission continues to charge patrons who enter the area, which has been damaged by Salgaocar’s operations.

New Frame sent questions to the Trust Commission’s acting chief executive, the director of cultural heritage and the director of parks, in August. No one responded.

The old mine remains on Unesco’s tentative list. With the active mine’s reopening in 2011, the process of evaluation was disturbed.

For Ngwenya Glass down the road from the mine, old problems will persist with the reopening of the mine. If the dust pollution continues for long, Gayter says, it might threaten the existence of the company that employs 80 permanent workers. The company also had solar panels installed not long ago. The dust is bound to render them useless.

Residents in Ngwenya, Mguleni, Nkhungu, Oshoek, Motjane and even as far out as Kupheleni and Makhwane complained about the dust in the three years the mine was in operation. They complained about the silt-filled water too, which they use for their gardens, livestock and laundry.

These residents were never consulted about the mine’s proposed reopening, even though they are directly affected. A Vuka Lilanga representative called a meeting at the Ngwenya Town Board hall and informed residents of the small village in Ngwenya of its plan. The many villages in the communal land on the peripheries were ignored.

Related article:

Vilakati says Vuka Lilanga was not there to consult residents. Rather, “we were simply told what’s going to happen. And there is nothing you can do about that, can you?”

That was in May. Machines will come rolling in soon. No one dares protest aloud.

*Not her real name for fear of victimisation.