Parasite and class-war cinema

The huge success of Bong Joon Ho’s cinematic masterpiece reflects global anxieties about capitalism in an increasingly unequal world.

Author:

4 February 2020

On the surface, the annual Hollywood award season may seem like a frivolous parade of red carpets and tearful acceptance speeches. But it’s a serious business of behind-the-scenes politicking, with producers and film studios using relentless marketing and personal campaigning to ensure their films receive awards nominations.

This year’s award season, however, has been defined by the subversive on-screen class consciousness of two of the most nominated productions. The first is Todd Phillip’s Joker, a reinterpretation of the Batman villain for the age of Donald Trump, incels and live-streamed mass shootings. The other is South Korean director Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite, a black comedy with impeccable acting and cinematography about the gothic power struggle between poor and rich families in Seoul.

Related article:

Parasite is the first non-English language film to win the Screen Actors Guild ensemble cast award, which many commenters see as a strong indicator of it winning Best Picture at the Oscars, the most coveted accolade in the global film industry. But the United States-centric bias of the movie industry means a non-English film has never achieved this honour. Last year, Mexican art film Roma was relegated to Best Foreign Language Film, despite being the critical frontrunner for Best Picture. Bong has used his award run to challenge this language bias, telling the audience at the Golden Globes, “Once you overcome the one-inch barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films.”

The acclaim that Parasite has received underscores Bong’s status as one of the most significant film directors working today and serves as a global validation of the new wave of Korean cinema. For the past two decades, South Korea has produced a string of remarkable crime thrillers and horror films that confront social ills with a directness from which Hollywood often shies away.

Bong’s work in particular is rooted in themes of social inequality and deals with sympathetic, impoverished leading characters confronting the brutalities of the state and capital, with often tragicomic results. This thread runs through his work, as is evident in the monster/family saga The Host (2006) and the postapocalyptic action Snowpiercer (2013).

Out of the pit

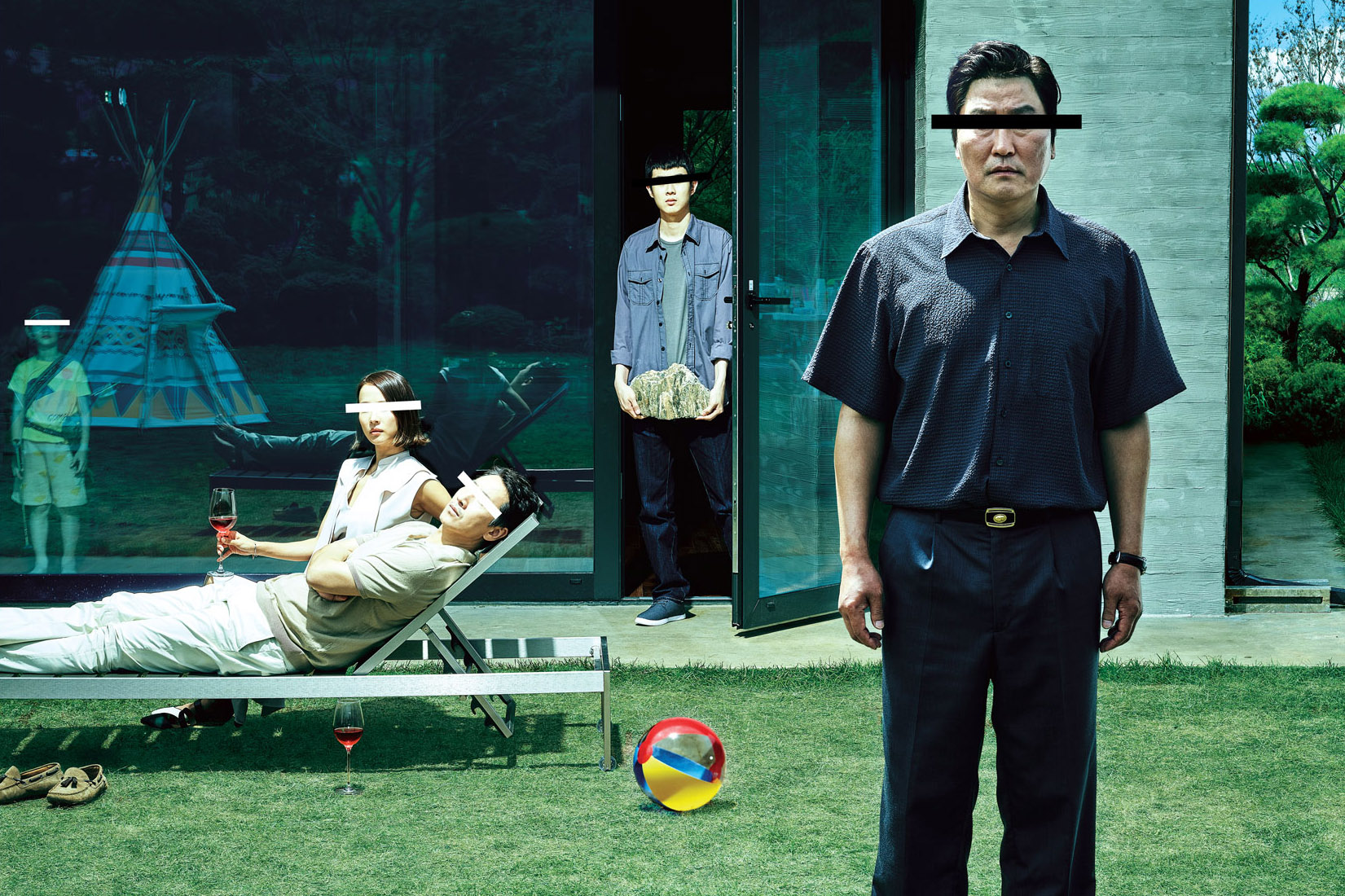

Parasite drops the fantastical elements to focus squarely on the dark absurdity of everyday life under capitalism. The film revolves around the Kims, an improvised, but highly talented and resourceful family who live in a miserable, foul-smelling semi-basement apartment. When son Ki-woo gets a lucky break as an English tutor to the wealthy Parks family, they begin to see a way out of the pit.

Through an ingenious series of schemes, the Kims begin to stealthily insert themselves into the lives of the arrogant and gullible Parks. Pretending to be loosely associated professionals rather than a family, the father becomes a driver, the mother their housekeeper and sister Ki-jeong becomes an art tutor.

The first half of the film has us rooting for the Kims as they continually outfox the Parks. It takes great pleasure in showing the lower ranks manipulating their economic superiors, through both the Kims’ tenacity and creativity and the Parks’ naivety and arrogance.

But a shocking reveal halfway through the narrative tragically complicates things. The Kims’ plans to escape their basement hovel begin to unravel. In one disgustingly memorable scene, their home is flooded with sewer water. And that is just a taste of the horror and despair the narrative still has in store for them.

Related article:

An underlying aspect of the film is the question of who or what is the parasite? Is it the Kim family, who are scamming the Parks? Is it the Parks, who expect the Kims to indulge their every pampered whim? Or is the parasite the capitalist system, a global monster that tricks us into doing its bidding with the illusion of a better life?

As with Bong’s previous films, Parasite is inspired by South Korea’s tumultuous political history and rising wealth disparity. The film shows the squalid reality of impoverishment and broken dreams behind the gaudy facade of K-pop and high-tech electronics. But the film’s ideas are also intended to be globally applicable. As Bong described it in an interview: “I tried to express a sentiment specific to Korean culture, [but] all the responses from different audiences were pretty much the same. Essentially, we all live in the same country, called capitalism.”

High and low

The film makes global class divisions literal through the way it uses architecture and living spaces. It shows the poor living in dark, cramped basements and underground dives. By contrast, the Parks live in a well-lit, glass house with a lush garden. The recurring image of staircases is used to show how the power of the wealthy takes on a vertical dimension as they rule over all from on high. Interestingly, the image of the staircase is also present throughout Joker.

As a video essay by film analysts The Take puts it, this vertical theme is central to the tradition of high and low-class dramas, which dramatically contrast the lifestyles of different social groups. The most famous original representation of this subgenre is Fritz Lang’s German expressionist masterpiece Metropolis (1927). In a vast futuristic city of soaring skyscrapers, the poor toil in the depths beneath the heel of a fascist state while the idle rich frolic in rooftop pleasure gardens. Ignoring the antifascist subtext of his work, Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels notoriously asked Lang to run the Nazi film propaganda apparatus. Lang wisely responded by fleeing Germany.

In the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, the themes of Metropolis continue to resonate in cinema. In 2012, Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises used it as inspiration for a story about a populist revolution within the Batman universe. Despite an ambitious premise, the film embraces a conservative message about the dangers of social change. While it acknowledges that oligarchy and inequality are social ills, it depicts revolution as indistinguishable from terrorism, literally ending with Batman and the police fighting to restore the status quo.

Related article:

Fortunately, many other film dystopias reflect more radical and interesting political stances. Bong’s Snowpiercer is a sympathetic portrayal of revolt on a massive train that contains the last survivors of a global cataclysm. The film’s cynicism about capitalism is bone deep. Its ending suggests that greed and exploitation have irrevocably corrupted civilisation and that the only recourse is to destroy everything and start again.

English director Ben Wheatley’s retro High-Rise (2015), based on JG Ballard’s 1975 novel about an apartment block descending into tribal warfare, parodied the rise of Thatcherism in Britain. In Wheatley’s vision, unrestricted capitalism is rooted in the desire to dominate and hurt those of lower social status.

But perhaps the most radical vision to date is the American comedy Sorry to Bother You (2018). Written by Marxist Boots Riley, the film is a dark, angry satire on how the high-tech capitalism of Silicon Valley affects ordinary people. Focusing on the surreal misadventures of a call centre worker the film skewers issues like poorly paid labour, office racism and the outrageous pretension of tech company bosses. As with Parasite, it also shows how working people are seduced by aspirational desires, at the cost of personal integrity, relationships and happiness. Riley doesn’t just settle for critique, the film openly calls for revolt by the oppressed.

Parasite has brought these critical themes into the elite circles of Hollywood. Its success is ultimately a testament to the talent of the cast and crew. But it also highlights how global wealth and income disparity is impossible for the entertainment industry to ignore. Bong didn’t need to imagine a fictional dystopia. Instead, he captured the bitter reality of the world we already inhabit.