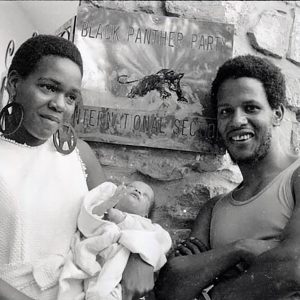

Part one | A Black Panther love story

Charlotte and Pete O’Neal fled the United States when he was targeted as a member of the Black Panther Party. Part one of their extraordinary story tells of their origins.

Author:

16 February 2021

Charlotte Hill O’Neal is known by several names. Residents of the Arusha region of northern Tanzania, where she has lived for decades, call her Mama C as Charlotte is difficult for Tanzanians to pronounce.

Others call her Mama Africa because of the scarification on her cheeks and the ring piercing her nose, and because she encourages the local youth to be proud of their culture and heritage.

Her Orisha spiritual name is Osotunde Fasuyi. She was initiated several years ago as a priestess in the Yoruba belief system, which originated about 10 000 years ago in present-day Nigeria. Enslaved Africans brought it to the Americas and the Caribbean, where it syncretised with other belief systems and is now practised throughout these areas.

Charlotte is bedecked in jewellery and beads. Some items represent Orisha deities and others are traditional Maasai beadwork.

She is a former member of the Black Panther Party, who fled the United States with her husband Pete O’Neal half a century ago.

Charlotte speaks Swahili with a Midwest drawl and her skin is decorated with tattoos: a black panther on her left shoulder and Sankofa, a symbol the Akan people of Ghana use to represent the importance of gaining knowledge and wisdom from the past, on her arm. African instruments, including the stringed nyatiti traditionally played by the Luo of present-day Kenya, replace the gun once strapped across her body.

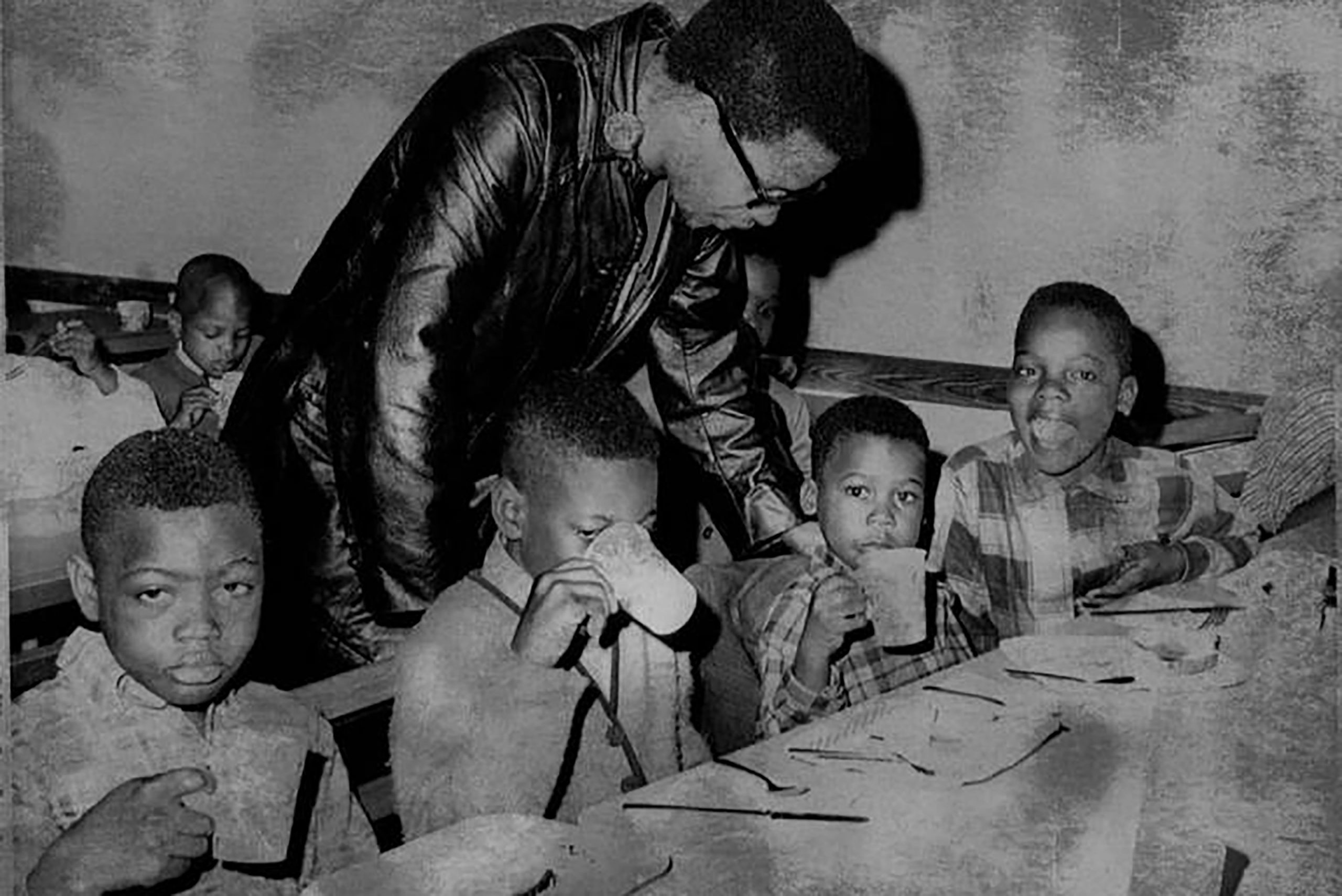

Charlotte, 69, and Pete, 80, have lived in Tanzania since 1972, when local authorities targeted Pete because of his activities as chairperson of the Kansas City chapter of the Panthers. They run the United African Alliance Community Center (UAACC) in Imbaseni village outside Arusha city, where murals of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr, along with other icons of the black power and civil rights movement, are splashed on to the walls.

Charlotte and Pete’s story intertwines with the revolutionary spirit of thousands of young African-American men and women who attempted to stand up to injustice and change the world, but were met with prison sentences, assassinations and government repression.

A confusing, beautiful time

While their relationship is a testament to decades of love and support, “I just really didn’t like her,” Pete says, laughing as he relaxes in their bedroom. Pete joined the Black Panther Party in 1968 after having an “epiphany” during a visit to Oakland, California, where the Black Panthers were founded in 1966. “I was not a very good person,” says Pete, who was incarcerated as a teenager in California. “I was a crook and a thief. My life mirrored so many young Black men and women growing up in the ghetto and who were attracted to the street life.

“My friends had convinced me to go with them to Oakland to see this new organisation, but I had no interest in trying to do anything to participate in the uplifting of our people or community. I thought maybe I’d go out there and do some hustles and make some money.”

Like many young Black Americans, it was the Panthers’ focus on police violence that initially attracted Pete to the party. He met co-founder Bobby Seale and high-ranking party member David Hilliard in Oakland and told them: “I’d be willing to do anything to get even with them [the police].”

“They stopped for a minute,” says Pete. “And they said, ‘Brother, that’s really not what we’re all about. We’re not about getting even. We’re trying to change the world.’”

Pete stayed in Oakland for several weeks and participated in the Panthers’ political education sessions, learning about revolutionaries from Che Guevara in Cuba to Mao Zedong in China.

Related article:

“I suddenly just had an epiphany,” he says. “I would imagine that this is what happens to born-again Christians when they see the light. Well, I saw the light. They talked to me about the suffering and the sacrifices that were made, and the beauty of stepping outside of your own desires and aspirations and embracing something larger than yourself.

“It was a confusing, yet beautiful time. It was like my mind was expanding and I could see things that I had not been able to see before. When I left there, I was a former street hustler imbued with the desire to bring about revolutionary change. Not just for Black people, but people of the world.”

Pete, who was 28 at the time, returned to Kansas City. “I severed ties to the people who were involved with me in my former life. I tried to take some of the people from my former life with me on this new path. But they thought I had lost my damn mind.”

He founded the Kansas City chapter of the Black Panther Party in the state of Missouri.

Far from love

Charlotte, meanwhile, was finishing high school in Kansas City, just kilometres from the city of the same name in neighbouring Missouri. “I was always raised to be very proud of who I am and my Africanness,” she says, the clinking of her jewellery as she gestures adding percussion to her speech.

“This was during the civil rights movement. Then I saw people like Malcolm X and then later with Stokely Carmichael, and then I started hearing about the Black Panther Party. It was amazing for me to see these young brothers and sisters with their black leather and shades, and their berets and all this marching,” she says.

Related article:

When Charlotte was a senior, she started seeing Pete in the newspapers and would cut out these pictures of him and paste them on her bedroom walls. “But I never thought I would actually meet him.”

Charlotte would soon meet Pete, though, and it would be far from love at first sight.

Charlotte was a successful student, but she often bunked school and crossed over to Missouri to attend political education courses at the Kansas City chapter. About two months after graduating, Charlotte officially joined the Black Panther Party. Pete was on a speaking tour and helping other branches, so he wasn’t there when Charlotte joined.

Charlotte was 18 and began living in a “panther pad”, where young Black Panther members would live in a communal environment and set an example of the revolutionary socialist society they hoped to build. “We cooked and cleaned together, and we would go out into the fields and have weaponry training,” Charlotte explains.

Strict code of conduct

The Black Panther Party had a strict code of conduct and warned its members against using or possessing narcotics, marijuana or alcohol while doing work for the organisation. “You’re not supposed to do hard drugs or anything when you’re on duty,” Charlotte says. “You were supposed to be very alert because the police were on us all the time. We weren’t supposed to give them any kind of excuse or reason to bother us, because they would harass us and arrest people just so they could deplete our finances by making it so we were constantly bailing people out.”

Signs around the panther pads and chapter offices warned members against being “non-functional”, Charlotte says. “But we were teenagers and this was the 1960s, right?” She tilts her head back, chuckling mischievously.

She and the other young Panthers decided to drop pills called Red Devils, the street name for secobarbital, a sedative-hypnotic pill used to treat insomnia and epilepsy that was used for recreational purposes in the US throughout the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

“So we dropped them and we were out of it,” Charlotte says. “We were having a good time. Everybody’s smoking, doing this and that. We were thoroughly non-functional.”

Talking back

The young Panthers were unaware that Pete was scheduled to return to Kansas City that day. He said: “I walked into the house, and I could get the aroma of illicit substances wafting through the air. I said, ‘What the hell?’ You could smell weed everywhere. And they were just partying on the porch with the music turned up loud. This is a political organisation. And they were just having a good time and I came up on them unexpectedly.

“Bear in mind,” Pete adds. “I was a father figure. Most of them were in their teens and, quite frankly, a lot of them were scared of me. So I came in and said, ‘What the hell is going on?’ And their mouths fell open and they were just staring at me and everyone was silent.”

Related article:

Charlotte was finally meeting the man whose image had adorned her bedroom walls. “I was so out of it,” she says. “I could hardly talk and I remember him being so mad.”

Pete, furious with the young Panthers, looked to his right and saw a young woman he did not recognise, a “skinny little girl with a big fat head”. He glanced at her and asked angrily, “And who the hell is this?”

The skinny girl with the fat head replied in a nervous stutter: “I-I-I’m Ch-ch-arlotte Hill. I-I-I’m from K-K-Kansas City. And I-I joined the B-B-Black Panther Party.”

“Who the hell let her join the party?” Pete responded furiously. He turned to Charlotte and said, “Shut up and don’t say another word.” But Charlotte retorted: “You can’t tell me not to talk. My daddy told me that I always have the right to talk.” The other young Panther members let out a collective gasp, Pete recalls. “They were thinking, ‘Oh Lord, she’s dead now.’”

“He was real mad at that,” Charlotte says, smiling from ear to ear and slowly shaking her head as she remembers being introduced to the man who would become her lifelong partner. “Brother Pete ran a real strict ship and here I was talking back to him.”

“I remember thinking that I can’t stand this girl,” Pete recalls. “I thought this girl was definitely going to be a disruptive force in the party. I didn’t like her.” As punishment, Pete made the young Panthers run, carrying each other on their backs, and then locked them in a storage cabinet. “I can’t remember if I left them there for a few hours or I left them there all night. I really can’t tell you,” Pete says, grinning. Charlotte, meanwhile, says she passed out soon after being locked inside.

But Pete and Charlotte were living together a few weeks later and soon after that, they married. “How did that happen? I really don’t know,” Pete said. “But what I do know is that she has been the love of my life, my greatest inspiration and my best friend.”

Part two of the O’Neals’ extraordinary story tells of their escape from the US and how they ended up in Tanzania.