Part one | Nuclear energy in Africa

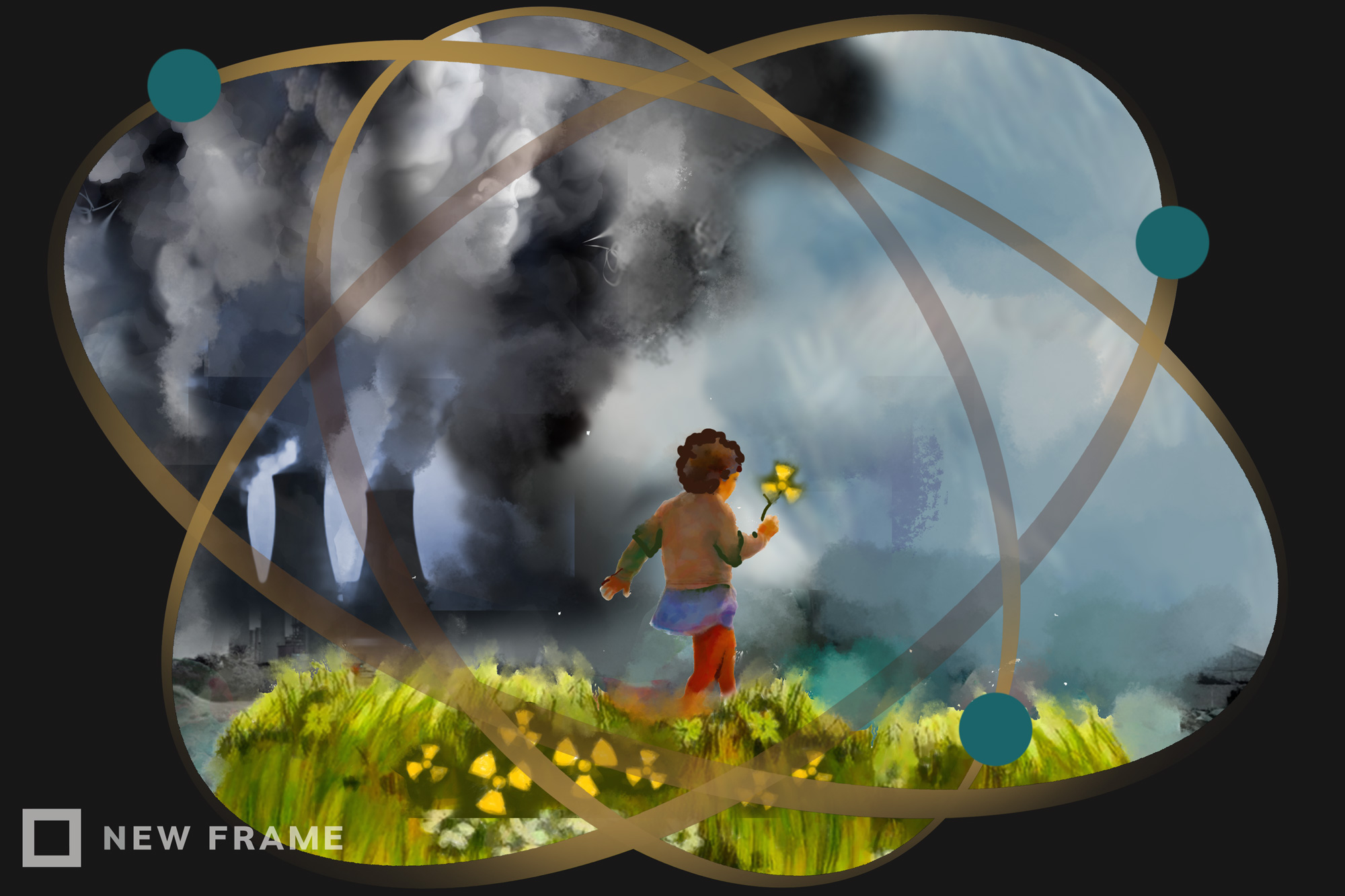

The first in this three-part series looks at the cost of nuclear power and how vendors minimise their financial risk by maximising profits through power purchase agreements with governments.

Author:

24 November 2020

At least 16 African countries have signed collaboration agreements with construction companies that are attempting to sell nuclear power on the continent.

These companies, which are generally known as nuclear vendors, view these collaboration agreements as the first vital step towards selling their diverse nuclear power technologies in Africa. They are making wild promises, claiming that nuclear power is the solution to the energy shortages in Africa that leave about 620 million Africans without access to electricity.

In reality, however, any African country that opts for nuclear power will burden itself with crippling financial and ecological debts for generations and generations to come. Nuclear power has never been, and never will be, the solution to the continent’s energy shortages.

It’s fairly common knowledge that the uranium used in the atomic bomb that American president Harry S Truman ordered to be dropped on Hiroshima in August 1945 came from the Shinkolobwe mine in the then Belgian Congo, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Related article:

What is less well known is that the Belgian Congo was also home to Africa’s first nuclear reactor. This reactor, which began operating in Kinshasa in 1959, was part of American president Dwight D Eisenhower’s 1953 Atoms for Peace programme.

According to Eisenhower, this programme was conceived to “help us move out of the dark chamber of horrors into the light” and it promised to turn nuclear energy towards peaceful purposes. In launching the programme, he stated that one of its “special purposes” would be to “provide abundant electrical energy in the power-starved areas of the world”.

Nearly 70 years later, nuclear vendors are making this exact same promise, with Russia’s state-owned Rosatom prominently leading the pack. At last year’s inaugural Russia-Africa summit in Russia’s southern city of Sochi, President Vladimir Putin, late to the second scramble for Africa and keen to counter China’s growing influence on the continent, said Rosatom was ready to create nuclear industries in as many African countries as are willing to embrace the technology. At the same summit, Rosatom director general Alexey Likhachev said nuclear power could provide the affordable and stable energy necessary for Africa to achieve its sustainable development goals.

Related article:

Rosatom has signed nuclear cooperation and provisional planning agreements with no fewer than 13 African countries to date: Tunisia, Rwanda, Algeria, the DRC, Morocco, Nigeria, Ghana, Ethiopia, Sudan, Uganda, South Africa, Angola and Zambia. In Egypt, the Russian energy company has been legally contracted and is scheduled to begin constructing a 4.8GW nuclear power station in El Dabaa in 2021. Chinese state-owned China General Nuclear Power Group has signed nuclear cooperation agreements with Kenya and Sudan, while France, home to state-owned nuclear company Électricité de France (EDF), has signed a nuclear cooperation agreement with Senegal.

While none of these agreements, aside from Egypt’s, have resulted in firm commitments, they demonstrate the extent to which nuclear power is being promoted throughout the continent. There are many reasons nuclear power stations are not the best solution for Africa’s energy needs – for example, they rely on extensive grid infrastructure that is lacking in many African countries and increase the dangers of nuclear proliferation – but the main problem is financial cost.

Fantastically expensive

Nuclear power stations have always been and always will be fantastically expensive to build. The Hinkley Point C nuclear power station that EDF is building in the United Kingdom will cost at the very least $29 billion (about R445 billion) and will become the most expensive object built to date. Rosatom is building a nuclear power station in Akkuyu, Turkey, at a cost of at least $22 billion.

Rosatom’s El Dabaa nuclear power station is to cost in the region of $29 billion. These colossal costs mean that private companies cannot afford to build nuclear power stations because of the size of the financial risks involved. French nuclear power company Areva went bankrupt in 2016, while America’s Westinghouse went bankrupt in 2017.

Those companies that can afford to do so, such as Rosatom, EDF and China General Nuclear Power Group, are state-owned enterprises that receive huge subsidies from their respective governments, often more for geopolitical than economic reasons.

Rosatom is financing 85% of the El Dabaa nuclear power station by lending Egypt $25 billion over a 35-year period beginning in 2029, at an annual interest rate from the point when the loan is made, of 3% ($750 million a year). The Egyptian government will fund the remaining 15% of the construction cost. According to Likhachev, Egypt has also signed deals to the value of $60 billion with Rosatom to cover the plant’s maintenance and to provide it with nuclear fuel during its operational life.

Related article:

There are no details as to what will happen if Egypt defaults on any of its repayments to Rosatom. In 2017, China took effective 99-year control of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port, which China had financed as part of its infrastructure-driven Belt and Road Initiative. This happened after it became apparent that Sri Lanka could not meet its 6% interest payments on the $8 billion loan from China for the port’s construction.

Will Rosatom take complete control of El Dabaa if Egypt defaults? If it were to do so, which entity would have control over issues such as electricity pricing and plant safety? These are serious questions that could have major implications for Egypt’s political and economic sovereignty, as well as its overall energy security.

Profits prioritised

While eventually the El Dabaa plant will be owned and operated by the Nuclear Power Plant Authority of Egypt, Rosatom is promoting heavily what is known as the Build-Own-Operate model in Africa. This model is essentially a public-private partnership whereby the vendor builds, owns and operates the nuclear power station on behalf of a state to which it then sells electricity.

This arrangement can continue until the end of the life of the power station, or ownership can be transferred to the state after a set number of years agreed to by both parties. This model enables countries that lack the necessary finances and technical skills to be able to consider nuclear power as part of their energy mix.

Related article:

Aside from the obvious geopolitical and domestic political risks involved with such a model, there are serious financial risks for African countries.

This model inevitably prioritises the financial aspects of any project. If a vendor is going to assume all the financial risk of building a nuclear power station, it is going to maximise the returns it can get from that station for the course of its life. This means it will maximise what it charges for the electricity the plant generates.

As Rosatom chief financial officer Ilya Rebrov indicated last month, a “project’s operational cash flow is the main source of investment repayment”. So, the electricity bills that consumers will be expected to pay in the future become the security for the investment in the present. These types of arrangements result in what is known as a power purchase agreement, also known as a strike price, which usually locks a buyer into purchasing electricity at a fixed price for a considerable number of years.

Part two looks at how these arrangements artificially inflate the cost of electricity, which has financial consequences for consumers and acts as a major source of inflationary pressure in economies.