Part one | Patric Tariq Mellet on slave towns

The Lie of 1652 is a richly textured book that calls for restorative memory and justice, and provides a decolonised history of land and identity in South Africa. This is part one of a Q&A with…

Author:

20 October 2020

Patric Tariq Mellet was born and “grew up in the working class districts of old Cape Town – Salt River, Woodstock and District Six”. The writer, heritage activist and former liberation movement cadre’s new book, The Lie of 1652: A Decolonised History of Land, calls for a critical reading of history and the restoration of Africa, our identities and our land.

In the book, Mellet writes: “Fundamental to resolving all the issues raised in this book is the need for all to embrace a drive for restorative justice and restitution relating to the land – our land and the African identity of our people. The cry over the decades calling for Africa to be restored may then be realised – Mayibuye iAfrika!”

Yvonne Phyllis asked him about the process of writing his book, the importance of a decolonised history of African identities and his analysis of the land question in South Africa.

Yvonne Phyllis: Your book is very rich. It is about your experiences, African history and the rewriting of African history in particular. It is also about reframing the land question in South Africa. Please tell us about your process. How much of it is personal? How much of it is research? How much of it draws from archives? And what methodology did you use?

Patric Tariq Mellet: The process is, to some degree, unorthodox. It’s as unorthodox as the book is. The first place or starting place is myself and my own sense of homelessness, of poverty, of where I fit in into this big picture. That was a lifelong process of development from childhood through to adulthood. Along that journey, lots of questions would come up that were not answered by what was placed in front of us as “education”.

First and foremost, I had a healthy distrust of education as I grew up, the contradictions just appeared everywhere. I didn’t have much of an education originally, three years in high school, what was called a trade school, a vocational training school – you worked with your hands, not your head.

Related article:

However, I had a mother who encouraged me to read, and I think the role of mothers in our life is extremely important. My mother couldn’t really look after me herself, most of the time I was in foster homes and institutions and so on. When she was able to have me, she took me to work with her. She herself had, I think, what we call a standard 2 [grade 4] education, very primary education. She worked all her life. When I was growing up, she was earning R5 a week in a laundry shop in District Six. She was also a garment worker. All of these things contributed to the platform from which I started, and the platform is extremely important to the process.

So part of the process was, if I was ever going to be useful to my broader community, and to be able to write, I had to equip myself. So, I put myself through night school, and through a master of science degree in the tourism and development arena, focusing on heritage tourism, around slavery and indigenous people. Through that process of doing a degree and writing a dissertation, I learned the skills that would help me produce a book like this.

For me, getting an education was about not getting an indoctrination, not getting canned education, but was about learning the tools of the trade. So by the time I started to think of writing a book, I was now equipped, both with life experience and with the tools of the trade. All of this was my process, it was a dialectical process within my own head, between me and my community and the society around me. It was about me asking the question all the time: What is it that people don’t know that I could help uncover? How can this empower people to understand where they come from, so as to know how to navigate the present and future? That was the methodology.

Phyllis: What are the key themes in your book?

Mellet: My preoccupation is how we change our mindsets; how do we begin to free our minds so that we can understand what restorative justice really means? It’s only by understanding, and opening our mind to a different history to the one of the colonialists that has been forced on us, then we are going to be able to develop the tools on how to end it. I’m informed by what Marcus Garvey had said about ‘none but ourselves can free our minds’. Bob Marley would later bring this into a wonderful song, the Redemption Song. As much as none but ourselves can free our minds, none but ourselves can free ourselves from the physical marginalisation and discrimination against working people in society.

This book is not a comprehensive history of South Africa, by any means. It’s five slices. I took those elements that for me were the most pressing ones. I wrote five papers originally. What I needed to do was, first of all, to break this notion that history started in 1652.

Looking at southern Africa, at least the past 3 000 years, with some introduction of the more ancient history, I show that we had a civilisation here in southern Africa, and that the civilisation traded with the world long before Europe traded with the world. We were making steel before Europe made steel. So my first thing is to get the ground right, that Africa wasn’t just about Stone Age and Iron Age peoples, that it was a social history that we had here. I looked at how peopling of southern and South Africa took place around the different rivers. That then led me into the next issue.

That this whole 1652 story, itself as a genesis of what would eventually become South Africa, was highly flawed. And I just took 50 years prior to Jan van Riebeeck, to show how we were already an international port at Cape Town, and that international port was run by indigenous people who serviced Europeans of five nationalities very well in terms of what they needed as travellers and so on, so that we look at a precolonial port of Cape Town and not just a post-colonial port. Within that [was] the very first struggle, the struggle for ownership and control over the port of Cape Town.

That then starts the trajectory that leads us to the third part, and that is our history books rigidly separated wars according to how the colonialists saw it. They simply saw two to four wars in the southwestern Cape and then nine wars in the eastern Cape. And then of course, if you go [to] broader South Africa, the Zulu wars and so on.

In the book, I limit myself to the Cape Colony. There were 19 wars. These wars were multi-ethnic in terms of resistance, they were African wars of resistance against dispossession. I wanted to tell that story in a coherent way. That story essentially is about loss of land, loss of livestock, loss of livelihood, loss of cultural coherence. The institutions of African societies were broken down, people were rapidly forced into proletarianisation outside of their original agrarian economies, very successful cattle-ranching economies.

Related article:

The next thing that was most important for me was to tell the story of migrants of colour, forced and voluntary. Right up through to the early 19th century, there were actually more migrants of colour than there were European migrants, but that migration was largely forced through slavery, through indentureship, migrant labour and so on. And the multifaceted ethnic tapestry, that was the forced migrants of colour, that story has not been told properly.

Then, having put those four slices together, I said, let us have another slice, which deals with how we were labelled. It wasn’t just people classified as coloured that were de-Africanised, all Africans in South Africa were de-Africanised. The conclusion is to say that what we have is not liberation but neocolonialism, because we haven’t addressed the core issues of what I call restorative memory. You can’t have restorative justice without restoring memory first.

I talk of the government pouring new wine into old wineskins, the old wineskins are apartheid and colonialism. And we all know that when new wine goes into old wineskins, it sours, it becomes vinegary. Also, the wineskins burst. That’s why we have a lot of bursting happening in South Africa.

Phyllis: You are very passionate about history, about narrating it truthfully and coherently. What is history to you?

Mellet: At the end of the day, real history is actually her story, his story, our story. For ordinary working-class folk, that is how you learn history, you tell them stories about people who are real. This book, unfortunately, couldn’t go into those dimensions, which I’m more fond of doing. You can empathise with a person rather than a place or event. You know, if people ask me, ‘Who are you?’, I say first and foremost I’m born of a people who rose above adversity. What was that adversity? It was colonialism, it was slavery, it was land dispossession, genocide, de-Africanisation, apartheid… It’s a different way of looking at it.

A lot of that came from being able to understand these forebears of mine. I had 24 enslaved forebears, five Khoe forebears and 19 European nonconformist forebears. Who were they? How did they land up in the situation that they found themselves in for the rest of their lives? How did they resist that? Or how did they navigate it? That to me is what history is about. It’s not about generals and political supremos and scientists and the big names and the powerful, it’s the power of the poor in history that is important to me.

Phyllis: There’s a term you use when referring to areas of cities where there is rampant unemployment and extreme poverty: slave town. Why do you prefer to use that term?

Mellet: For me, the term enslave, slavery, slave is full of meaning. As I say, 24 of my own ancestors were African and Asian slaves, enslaved people. This entire economy of ours, the colonial economy, in the Cape in particular, the infrastructure was built by people who were enslaved. White people say, ‘Look how hard we worked.’ No, you didn’t do all of this. The enslaved did this, the indigenous people did this. The building of roads, the building of cities and towns, clearing farms for cultivation, running those farms. Even the earliest animal husbandry and pest control, all of this. The Europeans required indigenous knowledge for this. However, the treatment of the people that they enslaved was cruelty in the most depraved way that you can think. From the manipulation of people’s reproductivity and ripping people who are in relationships apart from each other, and so on.

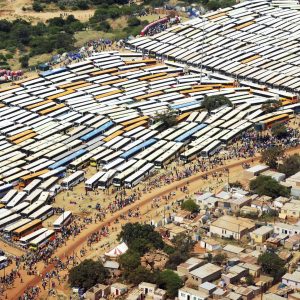

The slave lodge and the slave quarters have been with us from 1658, when the first 402 Angolan and Guinea slaves were brought to Cape Town. We had a building in Cape Town, which is the city’s third-oldest building, called the slave lodge. Today, it’s the Slave Lodge Museum. The whole area of the separation of slave-built environments and European-built environments begins right from the beginning. A little ramshackle place would be alongside the farm. You had the slave lodge in the city environment, where more than 1 000 slaves at one time would be residing in squalor.

When you go and you look at what happened at the formal end of slavery in 1834, and then enacted in 1838, you found that initially the settlers didn’t want the enslaved to become Christians. Why they didn’t want enslaved people to become Christians was that under the Dutch Reformed theology, there had to be the hope of freedom because according to them, in Christ, all people are free. So it was a contradiction. So it was not in their interest to have the enslaved people Christianised.

Related article:

So when slavery was coming to an end, the mentality changed. They said, ‘Well, we need Christianity now to create docile minds.’ They also didn’t want enslaved people having freedom and also Khoe people having freedom, to just walk and go wherever they wanted. They therefore created these mission stations right next to the white towns. So, slave lodges were then replaced with missions, and between the anvil of missionarism and the hammer of war and subjugation, they panel beat people into place.

I call these slave towns and not simply segregated towns because they were a progression on the slave lodge and on the system of mind control. And so, the slave bell becomes the church bell. If you go into any of these little small places like Peniel and so on, and you go to the centre of the town, there’s a Dutch Reformed Church and what was the slave bell is now the church bell. So you begin to see again, this thing of the control of the mind, the control of the body and the control of the social group woven into South African history from the earliest times.

Apartheid does not just suddenly magically appear in 1948, apartheid was simply the finessing of a system that was already in place. If you look at every single one of the apartheid laws, you will find corresponding laws, pre-1950, going back to 1910. Then if you look at the two colonies and the two Boer Republics, and you look at their laws and things, you’ll see the same pattern of segregating the laws, control laws, education laws, property laws that are all designed to keep people in their place, in the order of race superiority, with the European at the top of the ladder and then the different ranks of the ladder down to the least empowered, namely the San people.