Part two | Sport and the climate crisis

In the second of a two-part series, the focus is on what sport can do to reduce its footprint, whether it’s changing the way stadiums are built or the food that is served to fans.

Author:

24 February 2021

Amid the charred remains of a bush fire in the Australian state of Victoria, green shoots spring from the blackened earth. “It’s actually quite beautiful,” says retired netball player Amy Steel, 31, from her hometown, Melbourne.

“It was sad when all you could see was ash and soot. It felt like it might be that way forever. But the trees have begun resprouting. The majority are coming back to life. There’s green everywhere now and hope that it will be as it once was.”

Steel is undergoing a period of regrowth herself. Five years ago, she was a high-performing athlete representing her country. She had been enrolled in Netball Australia’s professional programme since she was 15. Her physicality was an integral part of her identity. Then, like a eucalyptus caught in an inferno, the life she knew was incinerated in a flash.

“It was March 2016,” Steel says, recounting a tale that is still difficult to tell after all these years. “It was a preseason game in Shepparton, a small town about a three-hour drive from Melbourne. It was a scorching day, around 39°C, when we were signing autographs in the town centre. By game time I was already cooking.”

Related article:

Inside the indoor arena, Steel, then 26, and her Adelaide Thunderbirds teammates were warming up for their match against their rival Melbourne Vixens. The humidity levels neared 100%. Ice packs offered little relief. A post-game ice bath only gave the impression that her body had cooled down. When she stepped out to the car park after the match, Steel’s legs gave way as she collapsed from heat stroke.

Her thermal injury, a term used to describe the irreversible cellular deterioration that occurs from severe overheating, meant that was her final game of netball. She can no longer exert herself beyond a light yoga session or a short swim. Runs and bike rides are out of the question. Sometimes, she needs multiple naps to make it to the end of the day. There have been times when she has been unable to get out of bed at all.

“I now know I’m lucky to be alive, but it has been a mentally and physically painful journey,” Steel says. “It took me a couple of years before I felt comfortable sharing my story.”

Steel was emboldened by friends who went public with their struggles with mental health. She recognised that as an athlete she had a platform to spread her message. She also recognised what was the root cause of her career-ending injury.

“I realised the climate crisis was not a problem for some distant future,” she says. “It was here already and had taken away the thing that had defined my life. With my whole day suddenly emptied, I found a new purpose. We’re all facing this together and sport has a major role to play.”

Obstacles in athletes’ engagement

When not working at her day job as a senior manager on Deloitte’s climate change advisory board, Steel serves as an ambassador for Eco Athletes, an organisation that seeks to amplify the voices of athletes who use their social standing to mitigate the climate emergency. Founded in April last year by Lewis Blaustein, Eco Athletes has recruited 32 athletes from a range of sports across the world.

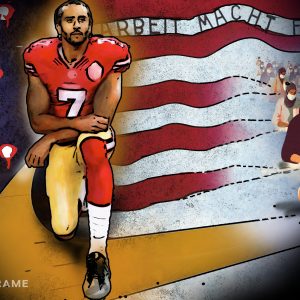

With a background in communication, Blaustein helps educate and empower athletes to lead the message about climate change. “What we need is to find the Megan Rapinoe, the Colin Kaepernick, the Mohammad Ali of the climate fight,” Blaustein explains. “Athletes have got involved and led on social and political issues going back decades. This is the biggest threat facing our species. Who better to shift the discourse than athletes who have demonstrated their influence time and again?”

According to Blaustein, three primary obstacles stand in the way of further engagement from athletes. The first is the perception that this subject is too scientific and difficult to articulate. The second is that it is too political, and wading into the divisive debate could turn away fans and sponsors and even draw the ire of coaches or governing bodies. The final barrier is that athletes who call for action could be labelled as hypocrites given their own carbon footprint, particularly those at the elite level who regularly fly around the world.

“The first two are easily addressed in our seminars and group discussions, but the third factor is a little more complex,” Blaustein explains. “There is no denying that athletes directly contribute to carbon emissions. We all do. But rather than shy away from the conversation, we encourage our athletes to say, ‘You’re right. I do fly a lot. Let’s all work together and campaign for low carbon aviation and a change in the scheduling of tournaments.’ It doesn’t have to be all or nothing.”

Related article:

During their 2017-2018 tour to Australia and New Zealand, England’s cricketers amassed about 62 440km by plane, more than 1.5 times the circumference of the Earth. Beginning and ending in London, the touring party zig-zagged across Australia and New Zealand for the better part of five months. There were four different journeys to Perth, three different journeys to Adelaide, two trans-Tasman Sea flights and multiple stops in Melbourne, Sydney and Hamilton. The flights alone left a carbon footprint equal to that of 100 citizens living out an ordinary life in the United Kingdom.

“A change to the calendar is something that would reduce sport’s impact on the environment,” says Dom Goggins, a consultant in environmental policy, who co-authored the 2018 Game Changer report that investigated how climate change is affecting sport in the UK. “Currently, tours are mapped out with profits in mind. We need to start organising these events with a different set of priorities.”

Change is possible

As is evidenced by the inertia surrounding the possible rescheduling of this year’s British and Irish Lions tour to South Africa, reorganising fixtures long set in stone can be difficult. But smaller, annual events, such as this year’s Australian Open tennis tournament, have adapted to the global travel restrictions enforced by the coronavirus pandemic.

“We’re clearly capable of change,” says David Goldblatt, author of Playing Against the Clock, a report published by the Rapid Transition Alliance outlining sport’s collision with the climate crisis. “Covid has given us a wake-up call. If nothing else, it’s emphasised that we need to take the science seriously. It’s shown us that, when confronted with the worst-case scenario, we can adapt.”

If the worst-case scenario plays out and we fail to meet the two targets set out by the Paris Climate Agreement – achieving carbon neutrality and preventing a rise of 1.5°C across the planet within the next decade – more permanent changes will be unavoidable.

In an effort to pull back from the brink, the Sports for Climate Action Framework was launched at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in December 2018. To date, 191 organisations have signed on, including the International Olympic Committee, International Federation of Association Football and Formula 1. This has created a global network of clubs and governing bodies committed to the adherence of five key principles: undertaking systematic efforts to promote greater environmental responsibility; reducing overall climate impact; educating for climate action; promoting sustainable and responsible consumption; and advocating for climate action through communication.

The framework gives signatories a blueprint for how to enact change and share what they’ve learned while allowing prospective members an entry point into the conversation. But, as Goldblatt outlines in his report, there are limitations: “There are, however, no targets in the framework, and no mechanisms of control, and, above all, an inadequate sense of urgency.”

More drastic steps are needed. It is not enough to sign a document and promise change. Goldblatt proposes that “all signatories must commit to draw up and publish a comprehensive 10-year plan that will ensure that their own operations and that of their sport are carbon zero by 2030”.

These measures must come from inside the organisation, but too often this is a bottom-up approach that inevitably bumps against a glass ceiling. The reason Forest Green Rovers Football Club is such a shining light in this field is because its chairperson, Dale Vince, has been the driving force for change. He made his fortune in renewable-energy company Ecotricity and has shaped the club in his image. Other clubs might have eco-conscious employees, but their ability to influence change is limited.

Related article:

Take Arsenal as an example. The Gunners sit in second place on the Sport Positive sustainability table that ranks Premier League teams based on their environmental sustainability practices. Last year, the North London club was tied with Manchester City in first place. However, both clubs are sponsored by airline companies, emphasising an imbalance in ideals at different operational levels.

The food frontier

There are smaller, more immediate fixes that could be achieved today. According to a 2018 study published in the journal Science, “A vegan diet is probably the single biggest way to reduce your impact on planet Earth, not just greenhouse gases, but global acidification, eutrophication [when a body of water becomes overly enriched with minerals], land use and water use. It is far bigger than cutting down on your flights or buying an electric car.”

This is why a shift towards animal-free, plant-based menus at sports stadiums should be the most immediate goal that we work towards. Granted, this could be a tough sell in countries hooked on meat. But as evidenced at Forest Green Rovers, it can be a success if done right.

“Football food is not among the best that you ever bump into, so we were competing with that, which was a very low bar,” Vince said on the Emergency on Planet Sport podcast. “But we make great food. We’re changing perceptions. Old timers at the club said we’d kill the club if we don’t serve meat. It’s had the opposite effect. Visiting fans go to their clubs and ask why they can’t have food like that. Food is actually an easy frontier.”

Other quick, doable solutions include installing electric vehicle charging stations around stadiums and solar panels on the ample roof space that most sports arenas have. A more costly but still achievable alteration involves the construction of new venues.

Barring the nuts and bolts, Forest Green Rovers’ new home will be made entirely from wood. As much as 75% of the carbon footprint of all stadiums in their lifetime comes from the materials they are made from rather than the energy used to power them for several decades. Concrete and steel are the biggest culprits. Wood, which is now being used to build high-rise buildings in Canada and Norway, negates this problem.

Fans can also have their say. In the past, vocal supporters have successfully protested against cities staging Olympic Games, club takeovers and increased ticket prices. Though their power is admittedly small, the people who fill terraces and purchase branded merchandise can exert pressure on owners and boards who fail to recognise the need for change.

Media influence

The media too must adapt. It is said often and loudly that sport is nothing without fans, but that is not entirely true. The coronavirus has emptied stadiums, but the show goes on because of broadcasters and journalists. This is not the only piece published recently that explores the relationship between climate change and sport, but it is still a rarity among the deluge of content built around transfer gossip, tactical analysis and jostling league positions.

Even subjects that stretch beyond the boundary such as the Black Lives Matter campaign and the pitfalls of the pandemic are regularly viewed through the prism of sport. The climate crisis will dwarf Covid-19 in terms of its impact on the games we play, and it will affect everyone regardless of race or class. Sport is a means of escape and even fist-in-the-air activists need a reprieve from the real world. But this looming catastrophe has to be front of mind for both content creators and consumers.

Related article:

Failing that, sport has an emergency ripcord it could pull. Days after the murder of Jacob Blake by police officers in Kenosha, Wisconsin, former world No. 1 tennis player Naomi Osaka withdrew from her scheduled semifinal in the Western & Southern Open, stating: “Before I am an athlete, I am a Black woman. And as a Black woman I feel there are much more important matters at hand that need immediate attention, rather than watching me play tennis.”

Osaka refused to be a tool of distraction while Black people were murdered with impunity in the United States. Sporting boycotts against apartheid South Africa’s rugby and cricket teams played a telling role in toppling that fascistic regime. Might a similar fate befall Jair Bolsonaro if national football unions refuse to compete against Brazil citing the rampant deforestation of the Amazon rainforest? Would governing bodies accept funds from fossil fuel companies if it meant they were barred from hosting a World Cup?

Beyond tweaks at the confectionary stand and the reduction of single-use plastic at live events, there are few short-term solutions. This will take a sustained and unilateral effort.

“The greatest threat to this planet is the belief that someone else will save it,” said Robert Swan, the British explorer and environmentalist. Unlike the effort against the coronavirus, there is no vaccine to guard against the climate emergency.

We cannot rely on scientists in a laboratory to fix this problem. As participants and lovers of sport, we must all play our part. We now have eight years to preserve our way of life. The clock is ticking.