Paulo Freire and popular struggle in South Africa

The Brazilian educator’s ideas influenced the Black Consciousness Movement and wider struggles against apartheid. For trade unions and grassroot campaigns, they remain important today.

Author:

2 December 2020

Although the apartheid state banned Pedagogy of the Oppressed, underground copies circulated. By the early 1970s, Paulo Freire’s work was already being used within South Africa. Leslie Hadfield, an academic who has written about the use of Freire’s work by the Black Consciousness Movement, argues that the Pedagogy of the Oppressed first arrived in South Africa in the early 1970s via the University Christian Movement (UCM), which began to run Freire-inspired literacy projects. The UCM worked closely with the South African Students’ Organisation (Saso), which was founded in 1968 by Steve Biko, along with other figures like Barney Pityana and Aubrey Mokoape. Saso was the first of a series of organisations that, together, made up the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM).

Anne Hope, a Christian radical from Johannesburg and a member of the Grail, a Christian women’s organisation committed to “a world transformed in love and justice”, met Freire at Harvard University in Boston in 1969, and then again in Tanzania. After she returned to South Africa in 1971, Biko asked her to work with the Saso leadership for six months on Freire’s participatory methods. Biko and 14 other activists were trained in Freirean methods in monthly workshops. Bennie Khoapa, a significant figure in the BCM, recalled that “Paulo Freire … made a lasting philosophical impression on Steve Biko”.

Between these workshops, the activists went out to do community-based research as part of a process of conscientisation. Barney Pityana remembers that: “Anne Hope would run what essentially was literacy training, but it was literacy training of a different kind because it was Paulo Freirean literacy training that was really taking human experience into the way of understanding concepts. It was drawing from everyday experience and understanding: what impacts it makes in the mind, the learning and understanding that they had.

Related article:

“For some of us, I suspect it was the first time that we came across Paulo Freire; for me it certainly was, but Steve, Steve Biko was a very diverse reading person, lots of things that Steve knew, we didn’t know. And so, in his reading he came across Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed and began to apply it in his explanation of the oppressive system in South Africa.”

Echoing Freire’s argument that it is only the oppressed who can liberate everyone, the BCM emphasised the importance of Black people leading the struggle against apartheid. Freire had also stressed that,”‘[w]ithout a sense of identity, there can be no real struggle”. This, too, resonated with the BCM, which affirmed a proud and strong Black identity against white supremacy.

The movement drew directly on Freire as it developed a constant process of critical reflection, part of as an ongoing project of conscientisation. Aubrey Mokoape, who had a background in the Pan-Africanist Congress and became an older mentor to the students who founded Saso, explains that the link between Black Consciousness and “conscientisation” is clear: “The only way to overthrow this government is to get the mass of our people understanding what we want to do and owning the process, in other words, becoming conscious of their position in society, in other words … joining the dots, understanding that if you don’t have money to pay … for your child’s school fees, fees at medical school, you do not have adequate housing, you have poor transport, how those things all form a single continuum; that all those things are actually connected. They are embedded in the system, that your position in society is not isolated but it is systemic.”

The workers’ movement

The Black Consciousness Movement included workers’ organisations like the Black Workers’ Project, a joint project between the BCP and Saso. The workers’ movement was also influenced by Freirean ideas through worker education projects that started in the 1970s. One of these was the Urban Training Programme (UTP), which used the Young Christian Workers’ See-Judge-Act methodology, which had influenced Freire’s own thinking and methodology. The UTP used this method to encourage workers to reflect on their everyday experiences, think about what they could do about their situation and then act to change the world. Other worker education projects were started by Left students in and around the National Union of South African Students (Nusas). Saso had split from Nusas in 1968 but, although largely white, Nusas was a consciously anti-apartheid organisation that was also influenced by Freire, primarily through members who were also part of the UCM.

During the 1970s, Wages Commissions were set up at the University of Natal, the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Cape Town. Using the resources of the universities and some progressive unions, the commissions helped to set up structures that led to the formation of the Western Province Workers’ Advice Bureau in Cape Town, the General Factory Workers’ Benefit Fund in Durban and the Industrial Aid Society in Johannesburg. A number of Left students supported these initiatives, as did some older trade unionists, such as Harriet Bolton in Durban. In Durban, Rick Turner, a radical academic whose teaching style was influenced by Freire, became an influential figure among a number of students. Turner was committed to a future rooted in participatory democracy and many of his students became committed activists.

Related article:

David Hemson, a participant in this milieu, explains that: “Two particular minds were at work, one [Turner] in a wood and iron house in Bellair; and another [Biko] in the shadow of the reeking, rumbling Wentworth oil refinery in the Alan Taylor residence. Both would become close friends and both would die at the hands of the apartheid security apparatus after bursts of energetic writing and political engagement. Both were influenced by Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, and these ideas and concepts infused and were woven into their writings striving for freedom.”

Omar Badsha was one of the students who was close to Turner and participated in setting up the Institute for Industrial Education. He recalls that: “Rick Turner was very interested in education, and like any intellectual we began reading, and one of the texts we read was Paulo Freire’s book that had just come out not so long ago at the time. And this book resonated with us in the sense that here were some valuable ideas about teaching and an affirmative way of teaching – taking into account the audience and how to relate with the audience.”

In January 1973, workers across Durban went on strike, an event that is now seen as a major turning point in worker organisation and resistance to apartheid. Hemson recalls that: “Out of the dawn they streamed, from the barrack-like hostels of Coronation Bricks, the expansive textile mills of Pinetown, the municipal compounds, great factories, mills and plants and the lesser Five Roses tea processing plant. The downtrodden and exploited rose to their feet and hammered the bosses and their regime. Only in the group, the assembled pickets, the leaderless mass meetings of strikers, the gatherings of locked out workers did the individual expression have confidence. The solid order of apartheid cracked and new freedoms were born. New concepts took human form: the weaver became the shop steward, a mass organised overtook the unorganised, the textile trainer a dedicated trade unionist, the shy older man a reborn Congress veteran, a sweeper a defined general worker.”

After the Durban moment

The period in Durban before and during the 1973 strikes came to be known as the Durban moment. With Biko and Turner as its two charismatic figures, this was a time of important political creativity that laid the foundations for much of the struggle to come.

But in March 1973, the state banned Biko and Turner, along with several BCM and Nusas leaders, including Rubin Phillip. Despite this, as unions were formed in the wake of the strikes, a number of university-trained intellectuals, often influenced by Freire, began working in and with the unions, which made rapid advances. In 1976, the Soweto revolt, which was directly influenced by Black Consciousness, opened a new chapter in the struggle and shifted the centre of contestation to Johannesburg.

Related article:

Biko was murdered in police custody in 1977, after which the Black Consciousness organisations were banned. In the following year, Turner was assassinated.

In 1979, a number of unions were united into the Federation of South African Trade Unions, which was – in the spirit of the Durban moment – strongly committed to democratic workers’ control in unions and on the shop floor, as well as the political empowerment of shop stewards.

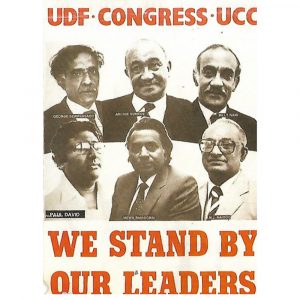

In 1983, the United Democratic Front (UDF) was formed in Cape Town. It united community-based organisations across the country with a commitment to bottom-up democratic praxis in the present and a vision of a radically democratic future after apartheid. By the mid 1980s, millions of people were mobilised through the UDF and the trade union movement, which became federated through the ANC-aligned Congress of South African Trade Unions in 1985.

Throughout this period, Freirean ideas absorbed and developed in the Durban moment were often central to thinking about political education and praxis. Anne Hope and Sally Timmel wrote Training for Transformation, a three-volume workbook that aimed to apply Freire’s methods for developing radical praxis in the context of emancipatory struggles in Southern Africa. The first volume was published in Zimbabwe in 1984. It was swiftly banned in South Africa but was widely circulated underground. Training for Transformation was used in political education work in both the trade union movement and the community-based struggles that were linked together through the UDF.

Related article:

Salim Vally, an activist and academic, recalls that “literacy groups of the 1980s, some pre-school groups, worker education and people’s education movements were deeply influenced by Freire”. The South African Committee for Higher Education (Sached) also came to be strongly influenced by Freire. The committee, first formed in 1959 in opposition to the apartheid state’s enforcement of segregation at universities, provided educational support to trade unions and community-based movements in the 1980s.

Vally notes that “Neville Alexander always discussed Freire in Sached – he was the Cape Town director – and in other education circles he was involved in. John Samuels – the national director of Sached – met Freire in Geneva.”

From 1986, the idea of “people’s power” became very important in popular struggles, but practices and understandings of what this meant varied widely. Some saw the people as a battering ram clearing the way for the ANC to return from exile and the underground and take power over society. Others thought that building democratic practices and structures in trade unions and community organisations marked the beginning of the work required to build a postapartheid future in which participatory democracy would be deeply entrenched in ordinary life – in workplaces, communities, schools, universities, etc. This was what was meant by the trade union slogan “building tomorrow today”.

Though there were strong Freirean currents in this period, they were significantly weakened by the militarisation of politics in the late 1980s, and more so when the ban on the ANC was lifted in 1990. The return of the ANC from exile and the underground led to a deliberate demobilisation of community-based struggles and the direct subordination of the trade union movement to the authority of the ANC. The situation was not unlike that described by Frantz Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth:

Today, the party’s mission is to deliver to the people the instructions which issue from the summit. There no longer exists the fruitful give-and-take from the bottom to the top and from the top to the bottom which creates and guarantees democracy in a party. Quite on the contrary, the party has made itself into a screen between the masses and the leaders.

This is an excerpt from a dossier first published by the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.