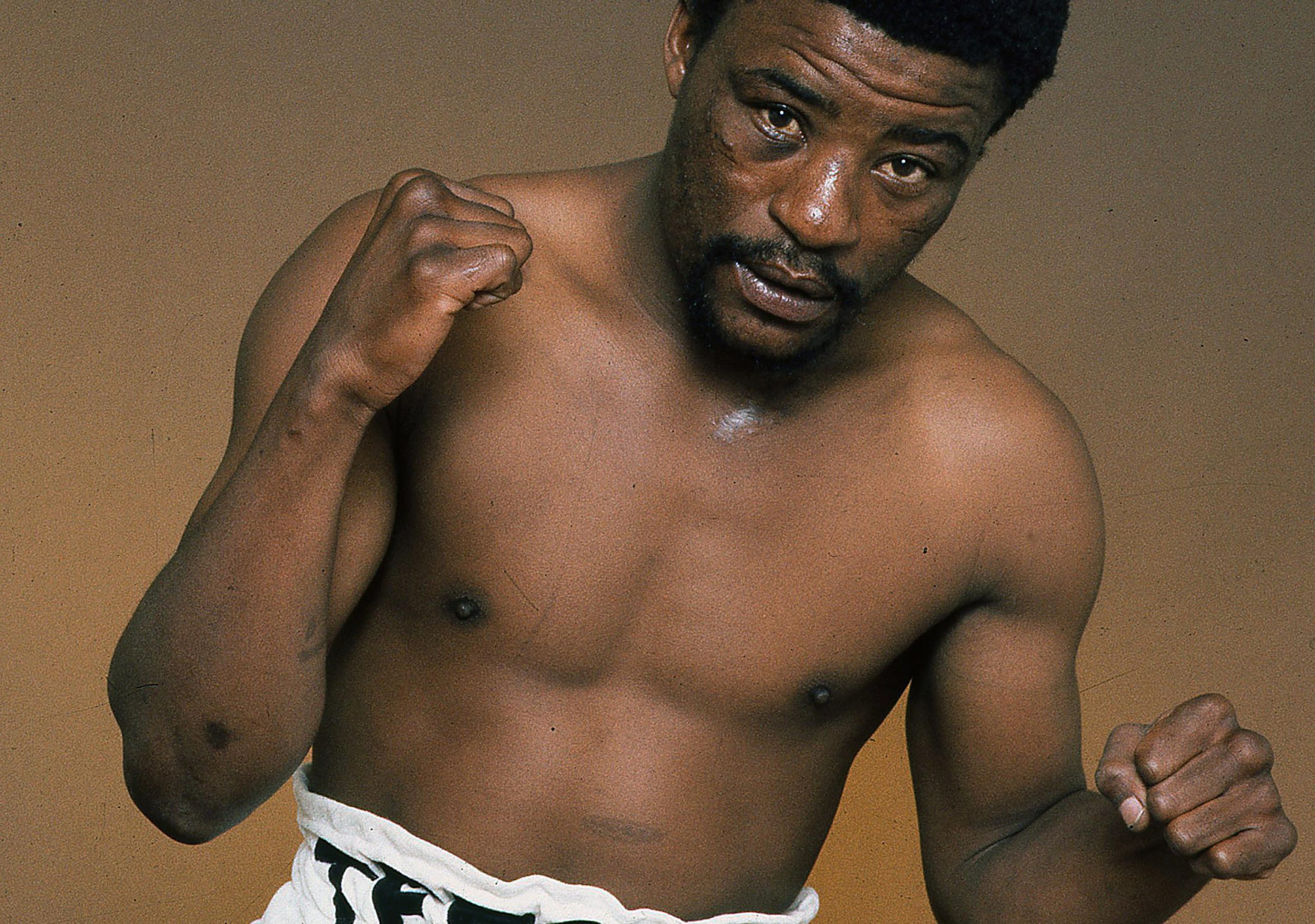

Peter Mathebula, SA’s first black world champion

The boxing legend etched his name in history by beating Tae-Shik Kim to win the WBA flyweight crown. But getting that fight wasn’t easy, with many obstacles in his way, including apartheid.

Author:

28 January 2020

The new decade had dawned with the promise of a world title shot for Peter “Terror” Mathebula, and then the clouds of uncertainty rolled in. In early July of 1980 the South African flyweight champion set off on his daily run from the Mohlakeng home he shared with his wife Gabaitsiwe.

As usual, his little black-and-white dog Monkie followed him on his route, which frequently varied.

Some days he would run 12km along the dusty roads of the township that lies on the western reaches of Gauteng, and on others he’d head to nearby mine dumps to assault their steep inclines.

At that stage he was uncertain if his crack at the World Boxing Association (WBA) flyweight crown would actually materialise, but he knew that if it did, he wanted to be ready. Mathebula, who died at the age of 67 on 18 January after a lengthy illness, got his shot at the end of that year, and victory made him the first South African to win a world title overseas.

That achievement, however, was largely overshadowed by the fact that he had become South Africa’s first black world champion. In apartheid South Africa everything was viewed through the prism of racial segregation.

The National Party government ultimately wanted all black people to become citizens of the shambolic homelands system. South Africa itself was reserved for white people, and Mathebula was supposed to belong to the newly created state of Bophuthatswana. But enforced ideology is no match for the power of humanity.

Mathebula was the WBA’s No. 2 contender when he was offered a shot at Tae-Shik Kim’s flyweight title in Seoul on 25 May. The offer had come at short notice, barely two weeks earlier, but his management had accepted. Mathebula had flown out to the Far East with trainer Raymond Slack and manager Bobby Toll.

Speed humps on Mathebula’s road to glory

The national boxing commission had sent its executive director Stan Christodoulou, who had refereed two fights in Korea before that, to accompany them. Flying via Mauritius they headed to Hong Kong, where they planned to get their visas for South Korea.

They were going to spend a few days there, so Christodoulou even arranged for a contact to organise a boxing gym and some sparring partners for Mathebula. But by the time they arrived in Hong Kong, South Korea had descended into chaos. The military dictatorship had just declared martial law to quell widespread protests. Visas weren’t being issued and the fight was postponed by a month or so.

Mathebula returned home soon afterwards to disarray at his gym, where Slack was involved in a dispute with another boxing manager, businessman Dave Wolpert. He and Toll left to link up with trainer Willie Lock, who was based in Yeoville.

Related article:

Meanwhile, Kim did defend his title the next month, but not against the South African as initially planned. He instead took on Arnel Arrozal of the Philippines in Seoul. Mathebula was promised a crack at the winner.

The Korean won a unanimous decision over 15 rounds, but he sustained heavy damage, suffering a broken jaw and an injured arm. While Mathebula waited during 1980, three white South Africans engaged in world title battles without much drama.

Welterweight Harold Volbrecht had lost to Mexican Pipino Cuevas in Houston in April. Bushy Bester was outpointed over 15 rounds by WBA junior-middleweight titleholder Ayub Kalule in Denmark in September. Mathebula had been offered a spot on the undercard, but Lock turned it down.

At the time Mathebula was preparing to face his friend and old foe Johannes “Slashing Tiger” Sithebe for the seventh time. Mathebula had won all six of their previous meetings on points, but this time, at the Jabulani amphitheatre in Soweto, Mathebula bombed his opponent into submission inside the distance.

And still Mathebula waited for his title shot. Gerrie Coetzee was given his second crack at the WBA heavyweight crown, challenging Mike Weaver at Sun City in October. Once again Mathebula was offered a spot on the undercard, but his manager effectively turned it down by demanding a then over-the-top purse of R10 000.

Fights outside the ring

They were still holding out for their turn against Kim. The Koreans had tried turfing him as an opponent completely, insisting now they didn’t want anything to do with a South African because of apartheid.

“Kim’s scared of me,” Mathebula joked at the time, but deep down he was worried his chance would never come.

At the time he had turned professional in 1971 white and black boxers were not allowed to fight each other. White fighters occasionally got world title shots, but black boxers didn’t. Enoch “Schoolboy” Nhlapo had been the star of Soweto boxing in the 1960s, but he never sniffed an attempt at a world title.

His successor, Anthony “Blue Jaguar” Morodi, got a little closer. In 1974 Morodi beat visiting Scotsman Jim Watt, a future world champion, but in his next bout just six days later, Morodi lost on points over 10 rounds to Tadios Fisher, a reasonable pugilist from neighbouring Rhodesia.

In the early 1970s Anthony “Qash” Sithole, another star of Soweto, had gone to Australia in a bid to secure his shot, but his effort was derailed when he returned home for a few months, losing his black SA bantamweight title to Joe “Green Cobra” Gumede.

Related article:

Gumede, who also held the black national flyweight belt, sparred with Arnold Taylor before his crack against WBA bantamweight champion Romeo Anaya in late 1973. “Green Cobra” had given Taylor, South Africa’s white bantamweight champion, a tough time.

Taylor won the world title, but Gumede’s stocks didn’t rise. He took matters into his own hands in early 1974, absconding shortly before a scheduled national bantamweight title defence to Mexico for a fight that had the potential of getting him into world contention.

He lost the fight as well as a second bout in Mexico City, and when he returned to South Africa he was stripped of both belts for ruining the tournament he was supposed to headline. But Mathebula had also witnessed major political changes within South African boxing.

The apartheid government had allowed the first mixed-race bout in December 1973 so the hero of white boxing fans at the time, Pierre Fourie, could take on world light-heavyweight champion Bob Foster, a black American, at the Rand stadium in Johannesburg.

The next step was permitting black and white boxers to fight on the same bills against international opponents. Then came black and white champions facing off in racial unification bouts for so-called supreme titles.

Partial end to segregation

In early 1979 the commission scrapped black, white and supreme titles, offering only provincial and national belts. It may have been a bold move at the time, but it hardly signalled the end of racist attitudes.

The decision was announced at the annual boxing awards, where Charlie Weir edged “Tap Tap” Makhathini in the voting for the coveted Boxer of the Year prize. Makhathini proved the electorate wrong less than four months later by knocking Weir clean out.

The South African boxing commission was a government structure with an all-white board that had been appointed by a cabinet minister. Made up mostly of lawyers and doctors, some of them enlightened, the executive had possessed the foresight to realise the world was turning its back on apartheid South Africa and they needed to change.

A key tactic had been courting the WBA, then based in the United States, and working their way into the sanctioning body’s structures. Christodoulou had got onto the ratings committee where he pushed South Africa fighters into the top 10. Mike Mortimer, one of the lawyers on the commission board, was chairman of the WBA’s championship committee.

The strategy worked.

From 1950 until 1975 only five South African fighters challenged for world titles, but from 1976 to 1986, 13 enjoyed cracks at WBA belts. Only five of them were black. An even smaller minority of four were successful. Norman “Pangaman” Sekgapane was the first black South African boxer to challenge for a world title in 1978, followed by Nkosana “Happy Boy” Mgxaji in 1979. Both were beaten by good champions.

Related article:

When the Koreans tried to sidestep Mathebula, Mortimer had prompted the WBA to threaten Kim to defend or be stripped. Backed into a corner, the Korean camp finally agreed to terms in November 1980. They opted to go for neutral territory, deciding on Los Angeles.

Mathebula was in superb condition by the time he stepped into the ring and he took the win on a split decision after 15 rounds of boxing. Mathebula became a household name in South Africa instantly, even being acknowledged by the Afrikaans newspapers that backed the apartheid government.

For a brief time the little man from Mohlakeng smashed through the rigid barriers of apartheid — a black man was a hero among white people. Mathebula lost the belt in his first defence early the following year, having spent too much time celebrating. But that’s a common story in boxing the world over.

His world title triumph, however, was unique. South Africa had to wait until March 1990 before another black boxer won a world title; Welcome Ncita was followed six months later by Dingaan Thobela.

Away from the public eye Mathebula and his wife Gabaitsiwe created a loving environment for their family.

Five days after his death, his widow collapsed and died at their home. They are mourned by son Patrick and daughters Theresa and Maggie, and nine grandchildren.