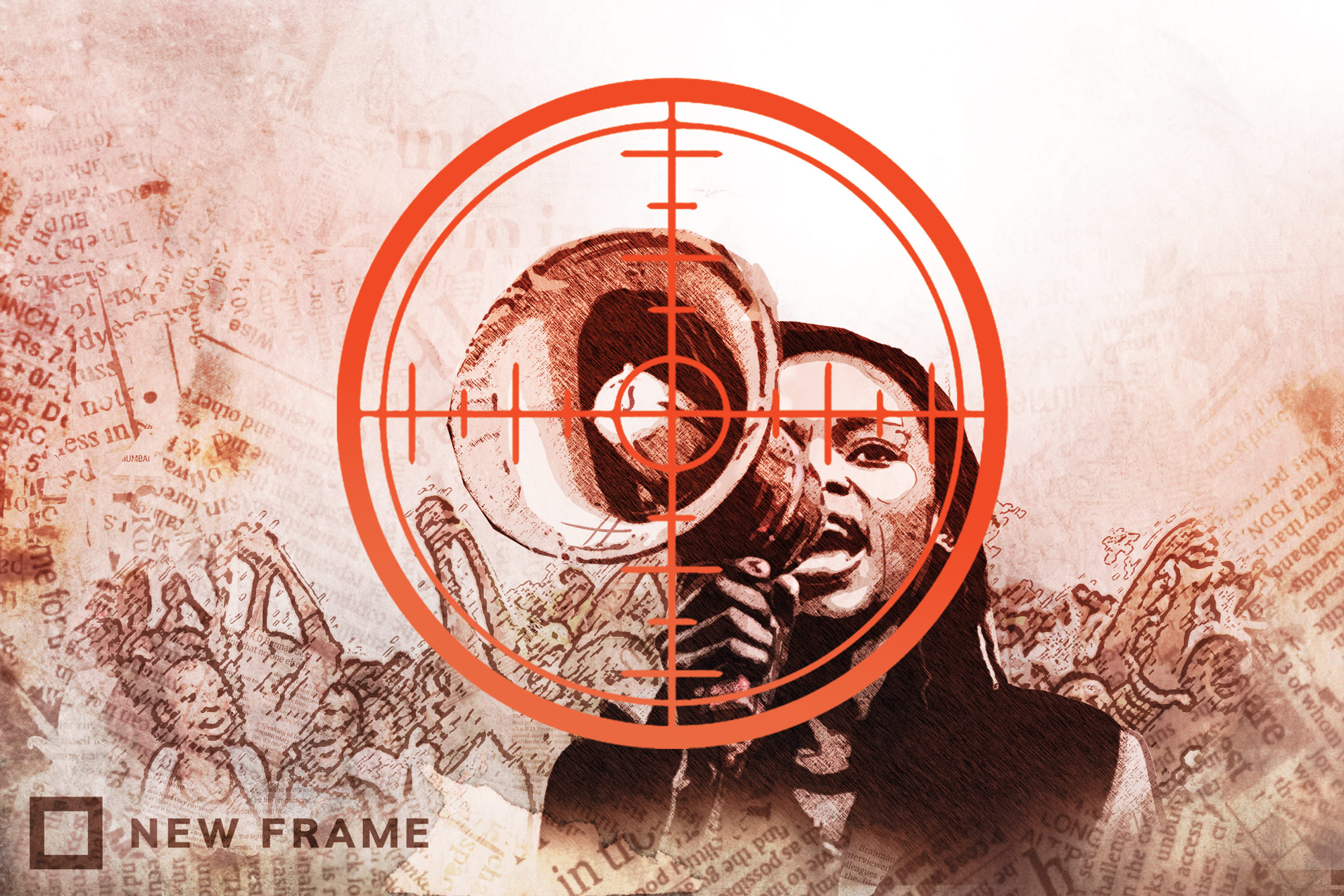

Political assassinations must be stopped

The use of murder to advance political contestation, and the kleptocratic practices enabled by access or proximity to political office, must be brought to an end.

Author:

3 September 2021

Political assassinations have been a routine feature of political contestation in KwaZulu-Natal for a long time. Although not exclusive to that province, there is no doubt that they have been overwhelmingly concentrated there. A careful study in 2013 documented more than 450 assassinations in the province since 1994.

Unlike the political violence that engulfed that part of the county during the late 1980s and early 1990s during the war between Inkatha and the United Democratic Front, and later the ANC, assassinations after apartheid have generally not been motivated by ideological concerns but by money and power.

There is no complete record of the number of political assassinations up to the present, a fact that illuminates the systemic lack of seriousness with which this issue has been received in the elite public sphere. What we do know is that while there are still inter-party killings, most assassinations are consequent to contestation within the ANC.

Related article:

This is not the full story, though. Government officials have also been murdered since at least 2005, and organisations such as the South African Communist Party, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa and shack dwellers’ movement Abahlali baseMjondolo have all suffered assassinations.

At least 13 members of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) were assassinated in 2013, in the wake of the Marikana massacre, as workers in the platinum belt abandoned the once powerful NUM en masse to join the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu). Now that the wheel has turned and workers are abandoning Amcu in large numbers, the threat of assassination stalks the area again. Mining – with its toxic intersection between capital, political elites and traditional authority – is often a site of political murder and a significant number of people opposed to it have been assassinated across the country.

The final point

Assassination is not the only way in which murder is used as a form of political and social control. The police routinely kill unarmed people at street protests, and police officers and other armed forces available to the state often kill people during armed evictions and disconnections from self-organised access to municipal services, most often electricity.

Assassinations are the final point in a continuum of violence and intimidation that ranges from assault to torture in police stations and threats of violence and assassination. They are a direct attack on democracy as well as the sanctity of human life. However, they have generally not been taken seriously in the elite public sphere because of the often implicit assumption that politics should be an intra-elite project, and the low value placed on the lives of impoverished and working-class Black people.

When the assassinations of such people are granted attention, it is invariably owing to one of two factors.

Related article:

The first is a connection to the elite public sphere through a relationship with non-governmental organisations (NGOs). This was true of the 2016 murder of Sikhosiphi “Bazooka” Rhadebe of the Amadiba Crisis Committee on the Wild Coast, as well as the murder of Fikile Ntshangase in Ophondweni in northern KwaZulu-Natal in 2020.

The second is via years of sustained organisation at sufficient scale and potency to force elite recognition. But this is not easy work and it is often received as criminal by the state and others in elite society. In a phenomenon well-documented elsewhere, this includes certain forms of middle-class leftism, usually located in NGOs and the academy, that prefer what Paulo Freire called the “praxis of domination” rooted in “manipulation, sloganising, ‘depositing’, regimentation and prescription” to the self-organisation of the oppressed.

But in the main, the elite public sphere – including much of the media, NGOs terming themselves “civil society” and elite forms of anti-racism – has systematically disregarded the scale of political violence in the country. It is not an exaggeration to say that the bulk of this sphere operates from the assumption that, as Frantz Fanon said of the colonial attitude, “they die there, it matters not where, nor how”. As Aimé Césaire, the great anti-colonial poet, said in 1950, colonialism has a “boomerang effect”; what is done over there will eventually be done at home. Césaire was making this point in regard to Nazism, which was inspired to a significant degree by British colonialism. But it holds in other instances. Consider the well-documented phenomenon of American soldiers who return from imperial wars to inflict violence on their families and wider society, sometimes in police uniforms.

A decisive end to impunity

In South Africa, what has long been permitted for them over there is increasingly happening to elites in elite spaces. This is true of brazen corruption, the rapid decay of the material infrastructure of social life, abusive policing, violence carried out within society and the murder of people opposed to political gangsterism, its entanglement with the state and the kleptocratic practices that follow.

The recent assassination of Babita Deokaran is an alarming and distressing instance of this. Deokaran is remembered by her colleagues as a hardworking person, committed to developing and sustaining the social aspect of the state, and a person of deep and inviolable principle. This is precisely why she was murdered.

Related article:

Along with her family’s pain and loss, the consequences of this assassination will include a reluctance on the part of others to speak out, and an exit of decent people from public service.

The fact that arrests were made so swiftly is welcome. The only way to stop the escalating use of assassination as a form of political control and domination is to put a decisive end to impunity. But putting an end to impunity means applying the same vigour in reporting, opposing and investigating all assassinations, including in the shacklands of Durban and the rural villages where mining interests crush other ideas about community and the management and use of land. This is imperative if our democratic moment is not to end in the everyday horrors of a society like Mexico or Guatemala.