Preserving Lovedale Press, a historical compass

The almost 200-year-old Eastern Cape publisher is facing closure, but a fundraising initiative that highlights its literary archive and importance as a cultural institution could save the press.

Author:

15 July 2020

The legendary poet BW Vilakazi had the future in mind when he wrote: “To all the generations coming after/ Now gaze upon the valleys here at Lovedale.” These words, from his poem Aggrey of Africa, may soon begin to ring false. While the educational institution remains, Lovedale Press in the Eastern Cape is at risk of closing down for good.

The press has been in dire need of funds for decades, struggling to meet even basic costs such as rent and salaries. Now, the situation has become so critical that they have no electricity or water supply, let alone a point of sales machine.

Only three custodians remain at the helm of this institution: Bishop Nqumbevu, Bulelwa Mbatyothi and Cebo Ntaka. They “have not drawn a stable income in close to a decade”. Yet they continue to work at the institution, with the understanding of what the press could mean to future generations.

The founding of an institution

Near a small town called Alice (Edikeni), about 33km south of the Amathole Mountains and about 60km west of King William’s Town (eQonce), one of the oldest educational institutions for black people in South Africa was established in 1841. The Lovedale Missionary Institute, or simply Lovedale, was founded in a region that was a battleground in the recurring frontier wars of dispossession, during which amaXhosa fought valiantly to fend off colonisers. It would later become one of the most famous missionary schools and training colleges on the subcontinent.

By 1887, more than 2 000 black students had successfully completed their secondary education at Lovedale. Many of these students would profoundly influence the intellectual history and political life of South Africa. For example, Cecilia Makiwane, the first registered black professional nurse on the African continent, was educated at Lovedale. Her mother, Margaret Majiza, taught at Lovedale Girl’s School.

Makiwane’s father, the Reverend Elijah Makiwane, was a teacher at the school and, in 1875, the second black minister to be ordained by the Presbyterian Church in South Africa. He, John Tengo Jabavu and William Wellington Gqoba became the first black editors of isiXhosa newspaper, Isigidimi samaXhosa, taking over from Lovedale principal and the publisher of Lovedale Mission Press, James Stewart.

The Makiwane sisters were some of the first young women to attend the Lovedale Girl’s School. Daisy was the first black woman to pass matric at Lovedale, receiving a special prize for mathematics. She became one of the first women journalists in South Africa, writing for Imvo Zabantsundu, which was founded and edited by Jabavu, her father’s former colleague. Thandiswa Florence Makiwane was a pupil and then taught at Lovedale before studying music at Kingsmead College in Birmingham, England. She later founded the Zenzele Women’s Self-Improvement Association.

Related article:

Other notable Lovedale students include political leaders Ellen Kuzwayo, author of Call Me Woman, Martha Ngano, founder and leader of the Rhodesian Bantu Women’s League, and Black Consciousness activists Steve Biko and Barney Pityana.

Many of the institution’s former students would also shape the country’s literary and cultural landscape. Notable examples would be poet and novelist SEK Mqhayi. He later wrote the classic isiXhosa novel Ityala lamawele. Isaac Williams Wauchope, a poet and one of the founders of Imbumba Yama Nyama (the South African Aborigines Association) in 1882, was also educated at Lovedale, as was Walter Rubusana, a minister and author of Zemk’inkomo Magwalandini. Gqoba, the writer, translator and editor of Isigidimi samaXhosa, and John Knox Bokwe, composer of the famous hymn Vuka Deborah and author of Ntsikana: Story of an African Hymn, were also Lovedale alumni.

The birth of the press

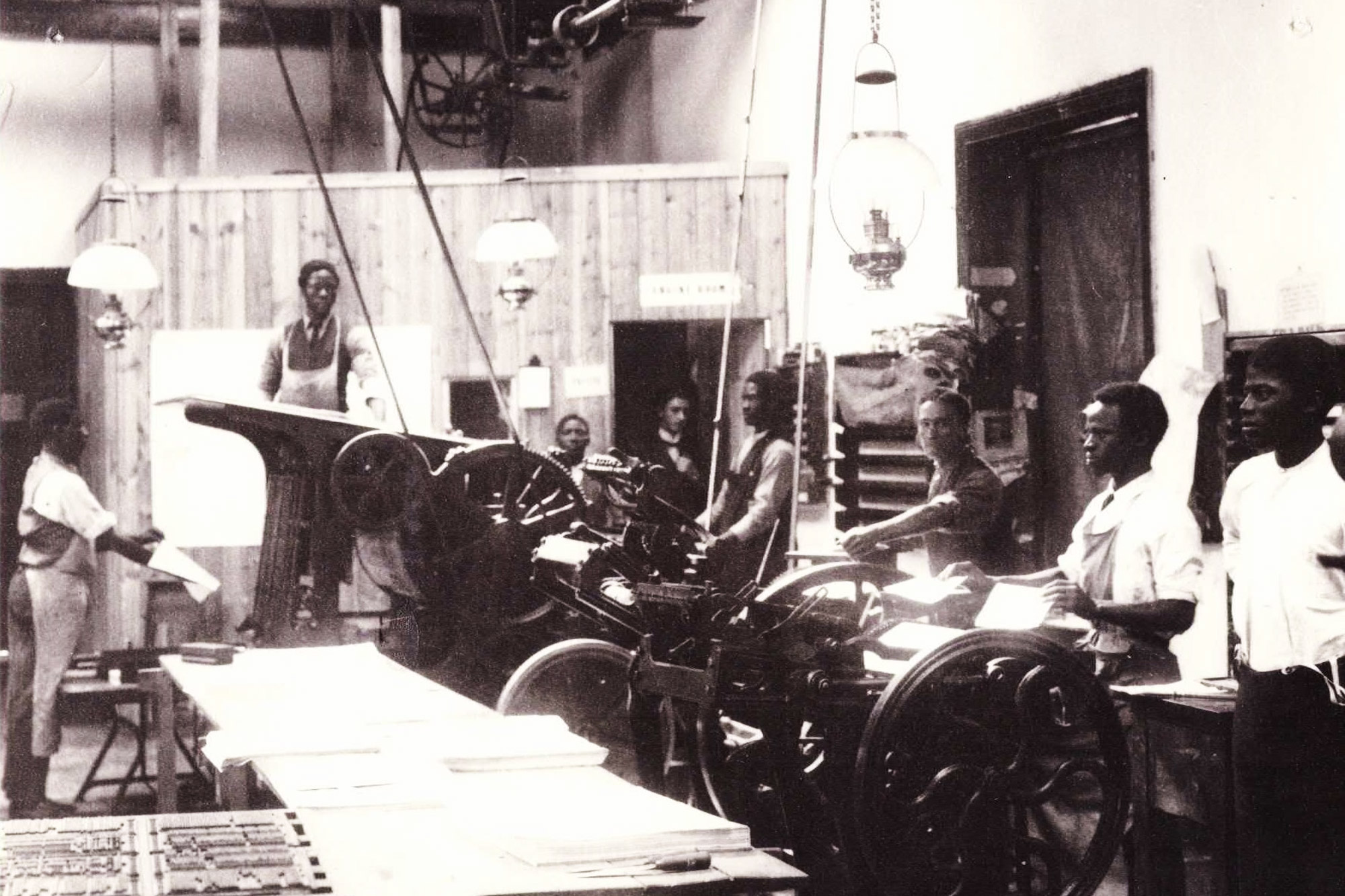

In 1861, the Lovedale Institution in the Tyhume Valley opened a printing department known as the Lovedale Press. Here the tradition of printing isiXhosa texts would go on, a continuation of the work started in 1823 at the Lovedale mission station.

About 5km east of Lovedale stands Fort Hare University, another institution that would come to occupy a central place in South African history. Many intellectuals and luminaries such as Phyllis Ntantala, Nozipho Ntshona, Frieda Bokwe, Nelson Mandela, Govan Mbeki, Oliver Tambo, Robert Sobukwe and Can Themba nurtured their political beliefs and intellectual rigour at the university. The press being so close to the university helped entrench a culture of education and writing among the black people of the Eastern Cape.

The press, even as it struggles presently, is a revered institution. It broke new ground by publishing black writers whose stories were shunned by white-owned presses. In due course, Lovedale Press became a major publisher in Southern Africa and built up an unsurpassed reputation for the production of rich literature in isiXhosa and other Southern African languages, including works in English.

Classic texts published by the press include Uhambo lo Mhambi (1867) by Tiyo Soga, an isiXhosa translation of the first part of The Pilgrim’s Progress; USamson (1907), the first novelette in isiXhosa; and Ityala lamawele (1914)by Mqhayi. An adaptation of Ityala lamawele was presented as a television drama series in the 1990s. To this day, although it is a work of fiction, it is recommended as a resource to students specialising in customary law.

The press also published An African Tragedy (1928) by RRR Dhlomo, the first novella in English written by a black South African, and Mhudi: An Epic of South African Native Life a Hundred Years Ago (1930) by Sol Plaatje, the first novel in English written by a black South African. Victoria Swaartbooi’s U-Mandisa would be published in 1934. Swaartbooi was one of the few women whose works were published around this time, an era when the publishing world was predictably gendered in favour of men.

Other notable publications include The Girl Who Killed to Save: Nongqawuse the Liberator (1936) by HIE Dhlomo, a poet, the deputy editor of Ilanga lase Natal and the first black dramatist in South Africa; Intlalo kaXhosa (1936) by TB Soga; Poems of an African (1946) by JJR Jolobe and Ingqumbo yeminyanya (1940) by AC Jordan. A translation of Ingqumbo yeminyanya titled The Wrath of the Ancestors by Jordan and Ntantala was published in 1980 and adapted for television in the 1990s. Alongside literary works, the press was also publishing works by black composers such as Bokwe, RT Caluza and B Tyamzashe.

All of these writers belong to a pantheon of literary legends. Their works are still appreciated and studied today.

Newspaper and journal publishing

Both Lovedale Press and the school were centres of black newspaper and journal publishing. Before the official opening of the press, the Lovedale Institution published a newspaper called Ikwezi between August 1844 and December 1845. The paper was a pioneering literary move as it contained the earliest known writing in isiXhosa. Among its eminent contributors were William Kobe Ntsikana, son of Sicana Ntsikana ka Gaba, reported to be the first black Christian convert, and Zaze Soga, brother of Tiyo Soga, the first black South African-ordained minister of the United Presbyterian Church in 1856 and son of Old Soga, who was an adviser to Inkosi uNgqika ka Mlawu of amaRharhabe.

Related article:

Indaba followed as the first newspaper of substance in isiXhosa. It ran from August 1862 to February 1865. Indaba became a mouthpiece for the first literate generation of black people to articulate their aspirations and ideas in a public forum in their own language.

In October 1870, Lovedale Press launched an English-isiXhosa monthly newspaper called Isigidimi samaXhosa. The newspaper acted as a vehicle for mobilising African opinion. Isigidimi ceased publication in 1888 after the sudden death of Gqoba, who had by then become its editor.

The press also published journals. Lovedale Press printed the famous Bantu Studies journal of the then department of bantu studies at the University of the Witwatersrand. The third and fourth editions of Black Review, a publication by Black Community Programmes, an organisation within the Black Consciousness Movement, were printed at Lovedale Press in the 1970s. The press is also known for its publication of school textbooks, a task it undertakes to this day.

Dealing with the National Party

Under apartheid, the press faced political challenges. During these years, Lovedale Press’ bookbinding department trained and employed black people as it championed the creation of a class of black printers and bookbinders.

During World War II, there was a shortage of paper and the cost of printing paper increased critically, but Lovedale Press somehow survived that turbulent time. However, an even stiffer test lay ahead.

When the National Party came to power in 1948 on the ticket of strict separation of races, the new government took a dim view of an institution empowering black people with such skills as printing, book publishing and more. A “war” soon began.

Through the Bantu Education Act of 1953, the Nationalist government instructed Lovedale Press to cut back its employment of black students studying printing. According to the newly promulgated law, printing was not an industrial course to be taught to black students. However, the press resisted and continued to train black students as printers.

Despite challenging beginnings, Lovedale Press held on and continued to publish important work by and for black people. Part of this success could be attributed to the Lovedale Press Literature Committee responsible for promoting the work of black writers.

This committee included politicians, writers, poets and academics. These luminaries were John Langalibalele Dube, the founder, editor and publisher of Ilanga Lase Natal; DDT Jabavu, a professor of bantu languages at the University of Fort Hare and leader of the All-African Convention; AJ Haile, the principal of the London Missionary Society’s Tiger Kloof Institute; and CM Doke of the phonetics department at Wits University. ZK Matthews, a professor at Fort Hare, and Jolobe also sat on the committee and acted as expert manuscript readers.

Hopeful initiatives

In spite of such a rich history and many past triumphs, the press has struggled in recent decades. The institution can still be saved, however. And some people are doing just that.

Visual artist Athi-Patra Ruga and voice artist, actor and academic Lesoko Seabe have banded together to work towards saving Lovedale Press. They have initiated Victory of the Word, “a three-phase fundraising and development project” to draw attention to and support the press and its custodians.

Ruga says: “Victory of the Word is a humble way of bringing attention to Lovedale Press and its current situation and struggles. Lovedale Press holds a legacy and a contemporary potential to carry those stories into the future. The publishing world has a need to answer in the revisitation of the isiXhosa or Southern African languages.”

In another initiative that draws attention to the press’ importance, Unathi Kondile, the former editor-in-chief of I’solezwe lesiXhosa, highlighted the African Languages Literary Heritage Colloquium scheduled to be held in November. Lovedale Press will feature prominently on the agenda.

The colloquium’s organising committee is headed by Pamela Maseko, a professor at North-West University, and Dion Nkomo, a professor at the university currently known as Rhodes University. Unathi Kondile, Sanele Ntshingana, Emmanuel Sithole and Thapelo Mokoatsi are members of the organising committee and researchers in the project.

“The colloquium seeks to bring together leading African languages and literary scholars and practitioners, historians, etc. to identify as well as raise awareness about the need for collection, documentation and preservation of literary works of African intellectuals from the 19th and 20th centuries,” says Kondile.

Related article:

Among other findings and projects, the colloquium will include the presentation of “an exhibition and working paper that provides a critical historical narrative on the history of literary sites such as Lovedale Press … It is also our intention to initiate interest in the establishment of a literary heritage route in the Eastern Cape, to ensure appreciation and preservation of identified literary sites and printing presses. Invited guests will be afforded the opportunity to present their own research around literary traditions of early African intellectuals, especially those who wrote in isiXhosa from these printing presses.”

In nearly 200 years of existence, Lovedale Press has faced turbulent times. Through the work of its custodians – whose urgent interventions draw attention to its existence as a key historical, literary and cultural institution – the press’ light continues to flicker. Support is needed to ensure that future generations continue to access and benefit from a historical compass in our literary heritage and contribute to this rich archive and legacy.

Support the project by donating or request more details @victoryoftheword and by email on victoryoftheword@gmail.com.