Puleng Mongale draws on home to fill the hollow

The Joburg-based artist explores feelings of displacement and hollowness through digital collages that incorporate images of home and those who have come before.

Author:

18 September 2020

“The origin of a story is always an absence,” writes novelist Jonathan Safran Foer. This is true for the story Puleng Mongale tells through her artworks. Her creations are spiritual and rooted in the ancestral, emanating from a hollowness and longing. “It is a feeling of displacement,” she says. “It’s almost as though something was taken away from me without my permission.”

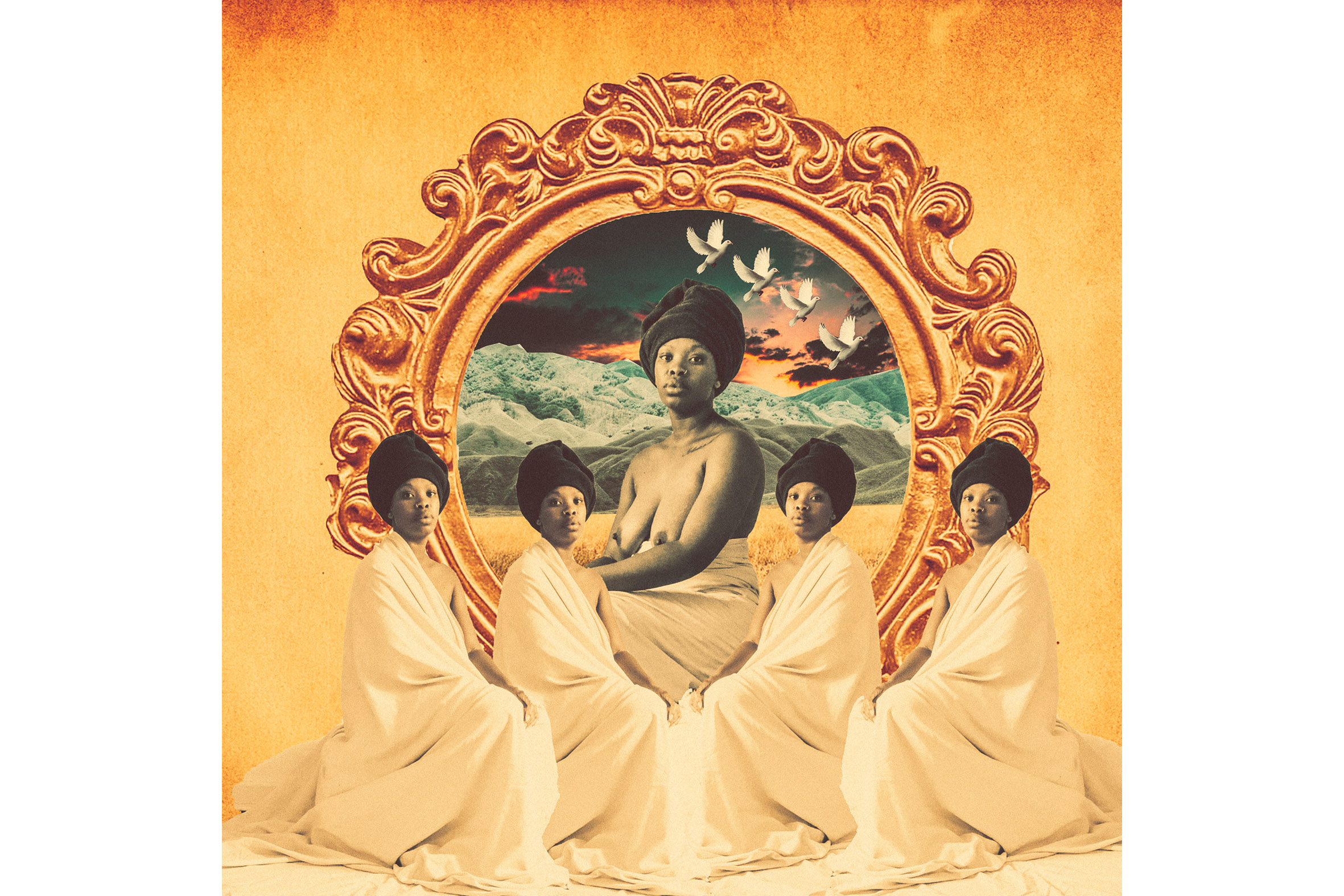

Her digital collages place a continuous journey in belonging at the centre. Playing with many replications of her own image, Mongale’s work is rooted in the idea that her story is not hers alone but another link in an ancient chain. Within this, her portrait signifies much bigger stories. In her artistic practice, Mongale represents herself in the images but is also a signifier of those that came before her and those around her now. She becomes aboMme, she becomes everywoman.

In the age of isolation, Mongale appears, on the screen, seated in front of an old kitchen cabinet as our interview begins. She is in her 16th-floor apartment in an art deco building in Johannesburg’s central business district. “I realise that I am telling a story that is way older than me. I am bringing things to the fore from a place from when I didn’t even exist,” the artist says. But before Mongale tells this much larger story, she starts with her own.

Mongale was born in 1991 in Orlando East in Soweto, where she lived with her grandmother and mother for seven years. She then moved to Naturena in Johannesburg South, living with her mother, father and younger brother. Her start in art, however, began with an ending.

Interested in telling stories, Mongale initially wanted to be a writer. Her career began in copywriting. She worked for several large advertising agencies, but was dissatisfied at the lack of a creative outlet. To express herself creatively, Mongale spent her downtime trying various things, including artistic styling and creative directing on photo shoots with photographers such as Khotso Bantu Mahlangu and Kgomotso Neto Tleane.

Related article:

It was during this time that Mongale styled and directed Intimate Strangers (2016), a four-part series of photographic works that explores “social commentary on labour relations”, “the feeling of brotherhood” and “a yearning for connection to and guidance from the ancestors”. In this moment of exploration, she also came across the work of Natalie Paneng. Paneng creates digital collages, often using self-portraiture. The artist was struck by Paneng’s collages, how their layered and complex approach was able to convey multiple stories in one image. She sent her partner, a photographer, a message saying that this was the kind of work she was interested in making. He responded immediately, saying he would help her learn how to use Photoshop.

From then on, she remembers spending weekend afternoons learning the programme and creating collages of her own. Then, in mid-2019, she was retrenched. It was then that Mongale picked up a camera and began producing in earnest digital collages fused with self-portraiture.

Her work includes City Girl Blues (2019), Cravings of a City Girl (2020), Encounters with the Departed (2020) and the recent series Home is a Feeling (2020), which is currently on show at the Latitudes Online Art Fair.

Preservation and inheritance

On her approach, Mongale says, “It takes me away from telling a singular story.” There are many ways she does this in her recent work. In Living to Remember (2020), Mongale is seated in the centre of the frame. She wears a doek, a traditional seSotho dress and a blanket around her shoulders. In the background, there is a lace curtain concealing a small window on the left, a table covered with a tablecloth and an enamel basin on it with a dishcloth hanging from its brim. On Mongale’s right is the familiar wrought-iron pot stand and a blue water drum.

Mongale purposefully uses objects as tangible, recognisable anchor points that communicate in a language understood by so many black South Africans. The objects are also familial; the props and sometimes clothes are borrowed from her mother’s home or garage and carefully curated for the image. It is this that Mongale has in mind when she says she is able to “insert herself into history, forge new worlds and document the present”. Her images are more than an exercise in archiving or preservation, they also document the now.

“My mom is quite a preserver,” Mongale says, speaking about the things her mother refuses to part with. “That’s another thing I have noticed about black mothers and black homes, they just have this thing of preserving things that are important to them. Something may not be of much value, but their ability to look after that thing makes it something very valuable. There is even a pot when I go back home to the Free State that belonged to my great-grandmother that no one is using, but no one is parting with. I guess that’s how we inherit things, as black people … Should my mother no longer be around then, yes, my son is definitely going to know those things. He is definitely going to see those things and see what kind of people we were.”

While the idea of inheritance is often thought of as having some kind of financial value, Mongale’s work shifts this to understanding inheritance as belonging, made real through artefacts and their stories. And there is perhaps no place more central to the question of belonging than home.

Belonging

Mongale’s Home is a Feeling series was born on one of her trips to her mother’s hometown of Fateng-Tse-Ntsho in the Free State. It’s a candid and intimate journey of her return home and in so doing, she takes others to home – or to its questions – too. While set in Fateng-Tse-Ntsho and featuring members of Mongale’s family, they could be set anywhere in South Africa.

The series differs from her collage work in that for all the images but one, the camera is turned away from Mongale and outwards at her family home. The vast, expansive Highveld with a long and dusty road appears as a woman walks, carrying an object on her head. The silhouette of a woman standing at a kitchen table washing dishes is seen, with the light pouring in behind her through the lace curtains. A cow grazes close to a road as rubbish is burnt nearby, her mother and son standing within frame. These images are again recognisable by so many who return “home-home”, the space most deeply imagined as origin.

The piece that gives the series its title features Mongale dressed in her Sotho attire. This is the only image from the series that features a self-portrait. She is foregrounded on a gravel road and flanked by replicas of her image on either side. The collage is striking in the way it shows how Mongale is a link in a chain that predates her and will outdate her. There is strength in this, in the way it speaks to soothing the hollowness and deep sense of dislocation she speaks about.

“Growing up in Soweto is also a displacement of sorts,” Mongale says. “I never really got to embrace who I was from a cultural perspective because I spent most of my life trying to align with what was dominant in the township … There was no room to explore where my beginning was.” Going home, then, is the ability to explore the idea of origin.

This also raises the conversation of the city as a sprawling, fast-paced structure that does little to locate or anchor. Mongale chuckles in thinking about belonging in relation to a city. “I mean, nobody is from Joburg, really, are they? I mean, I love the city, I have had some of the best times of my life here, but I feel that something is missing. When I do go home, I am full for the duration and when I come back to the city, the hollowness creeps in.”

Surrender

While belonging is so steeped in place, it is not limited to it. Belonging is anchored in many sites, including in commune. In journeying on this path, Mongale notes the need to surrender to her art as a vehicle of exploration as well as her own ancestral story. In Encounters with the Departed I (2020) and II (2020), Mongale creates ethereal divine imagery in an ode to those who have come before her. She is in conversation with the departed, encountering them as part of her bloodline.

In surrendering to her role in her ancestral constellation, Mongale must also surrender some control over her work. “I feel like my work teaches me things. I feel like my work carries messages for me. My work also turns me into an audience at some point … It’s not about me. It’s something bigger than me.”

Mongale concludes: “The work that I have done has taught me that pain doesn’t begin with me. That pain is a generational thing. It’s in our blood and in things that have happened. I am in a place now where I can look back and start to create from that place and from that memory. That I am not alone. I can lean on the knowledge of my ancestors, I can lean on the knowledge of the women in my life. I am not just made up of myself. There are many people that have come before me, there are many people that are in me, and that’s what’s going to heal me.”