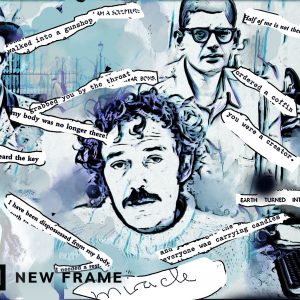

Recordable and portable: the cassette tape miracle

By providing a platform to loop, record and disseminate new music easily and cheaply, the cassette tape, whose inventor died this year, changed the world for musicians and listeners alike.

Author:

20 April 2021

While the now-obscure relationship between a cassette tape and a pencil may be in 2021 nothing more than an internet meme, in the 1970s the cassette tape developed into a revolutionary and subversive technology. The humble technology has altered the music world in ways that couldn’t have been imagined when Dutch engineer Lou Ottens launched the tape in 1963. Ottens died in the Netherlands village of Duizel on 6 March 2021, at the age of 94.

The cassette tape’s appeal was tied to its portability and affordability, signalling the beginning of the democratisation of recording and the distribution of sound. It gave many musicians who needed time to experiment the ability to record outside the expensive confines of a recording studio, allowing the development of new music genres and facilitating the greater independence of musicians and record labels.

In his book Assimilate: A Critical History of Industrial Music, academic S Alexander Reed writes that the cassette helped break down barriers between production, distribution and consumption. “It encouraged users to be fans, distributors, musicians and journalists all at once.”

Related article:

The liberating effect of the cassette tape can be traced across the music of the 1970s, impacting punk, hip-hop, ambient and industrial music – genres that without the tape might not have existed as we know them today.

The cassette tape also allowed the spread of ideas and played an important role in politics, both liberatory and oppressive, throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

US soldiers in Vietnam used the cassette tape to record messages for their families back home, while in Chile, under the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, a tape culture emerged in the 1970s to spread banned recordings. In the build-up to the Iranian revolution of 1979, cassette tapes of sermons given by Ayatollah Khomeini were disseminated throughout Iran, while in 1980s Libya, Tuareg refugees began recording their songs of revolution for anyone who could supply a blank tape, spreading the political concerns of their people. The fiercely independent Shifty Records released a string of politically charged tapes in 1980s South Africa, voicing opposition to the apartheid regime.

Tale of the tape

As head of product development, inventor Ottens, who had been working for the Netherlands-based electronics company Royal Philips since 1952, oversaw the 1961 launch of the first portable tape recorder and the 1963 launch of the cassette tape.

The cassette tape was based on decades-old magnetic tape technology, which had revolutionised the recording studio in the 1950s, allowing multitrack recording, overdubbing and editing. Ottens found that reel-to-reel tape recorders were cumbersome, prohibitively expensive and not very user-friendly, which motivated him to invent the cassette tape. His tape debuted at the Berlin Radio Show on 30 August 1963, with the tagline, “Smaller than a pack of cigarettes!”

But Ottens’ work was not done. In 1966, Phillips launched the Radiorecorder, coinciding with the first music released on cassette. The prototype of what would become known as the “boombox” in the mid-1970s, the Radiorecorder was followed two years later by the first car cassette deck.

The development of the portable tape recorder, the boombox and the car tape deck show the genius of the cassette tape – it made recording and listening to music portable, fuelling the popularity of the cassette throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

The subversive 1970s

Thinking through the subversive decade of the cassette tape’s existence requires a journey through place.

First, London. Synthesiser wizard Brian Eno has been credited with tape delay effects on the first two Roxy Music albums. After leaving the band in 1973, he would go on to explore tape delay and tape loops, producing celebrated experimental works such as 1975’s Discreet Music.

Discreet Music’s title track is a 30-minute piece Eno famously admitted had essentially composed itself. He had set up a synthesiser with a built-in memory, an echo unit, a graphic equaliser and a tape delay in a complicated system and then set it off, recording the result. Eno recalled how he set the equipment to begin recording and was immediately interrupted by phone calls and knocks at the door, so he left it to record, describing the piece as “automatic music”. The version he recorded that day was not the final one he released. First, he slowed down the piece on the tape to half its speed.

Related article:

In Sheffield, Eno’s experiments with tape loops had meanwhile inspired a new generation of younger musicians such as Sheffield’s proto-industrialists Cabaret Voltaire, formed in 1973 by Stephen Mallinder, Richard H Kirk and Chris Watson.

Imagine the scene. You walk into a public toilet in Sheffield and are accosted by a series of portable tape recorders playing strange sounds on loop, which together created some form of industrial soundscape. This is the beginning of Cabaret Voltaire, who alongside the London based proto-industrialists Throbbing Gristle, produced tape compositions that would map out the beginnings of what would become known as industrial music.

In Reed’s Assimilate, Mallinder says Cabaret Voltaire’s music was a combination of post-punk ideology, available technology and a do-it-yourself ethos. The resulting sound is still reverberating through contemporary music. As Mallinder says in Assimilate, “The actual sounds and processes on which the industrial music templates were drawn continue to echo through contemporary urban sounds of dubstep, grime and electronic dance music.”

Meanwhile proto-hip-hop producers in New York had begun creating loops of breakbeats. As Jeff Chang writes in his book Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation, DJ Kool Herc began in 1974 to use two copies of the same record to create a loop of a song’s breakdown, “extending a five-second breakdown into a five-minute loop of fury”.

Soon budding rappers were copying this technique, using a double-tape deck to create the break loop they needed over which to rhyme. The gigs of early hip-hop pioneers such as DJ Kool Herc, Kurtis Blow, Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa were often recorded to tape and spread throughout the community as “party tapes”, the first hip-hop mixtapes.

Podcast

The emergence of the boom box as a popular way to listen to music in the mid-1970s also meant that these tapes were now both portable and public, listened to collectively on the streets.

Back to London. Cabaret Voltaire’s fellow industrial music pioneers Throbbing Gristle, who had emerged from the performance art collective COUM Transmissions, were already well versed in the concept of mail art, which had begun in the 1960s with the Fluxus movement. Mail art involved sending small-scale artworks through the post.

Throbbing Gristle realised that mail art and the networks it had created were easily transferable to the distribution of their new music, so they set up their own record label, Industrial Records. In Assimilate, Reed writes that this “global network established through the Fluxus art movement” and the “cassette and small press cultures that arose in the late 1970s” were key to industrial music emerging. “Nearly every active industrial musician in the world from 1975 to 1983 participated in this network.”

Another direct influence on many of these early industrialists was the cut-up technique used by William S Burroughs in the 1950s and 1960s novels that make up the Nova Trilogy. By the 1970s, Burroughs was living in a Piccadilly flat in London busy creating cut-ups on tape, as industrial music was being born. “By cutting up and recording the sounds of industry, authority, religion, commerce and war, those who are held in their sway might be deprogrammed,” Burroughs wrote in his 1978 book The Third Mind, which he published in collaboration with Brion Gysin, the artist and poet who, alongside Burroughs, began experimenting with cut-up in the 1950s.

Related article:

Now to Manchester. Although punk music had been burgeoning in America and the UK for much of the early 1970s, when it fully emerged in 1976 as a cultural phenomenon, the musicians involved didn’t look to tape as a composition tool, but like the industrialists, they recognised the role it could play in recording and distributing their anti-establishment lyrics and songs of discontent.

While the first wave of punk bands such as The Sex Pistols, The Ramones and The Clash were signed to established record labels, a whole wave of unsigned punk musicians went about self-producing and recording their own music. Manchester’s Buzzcocks self-recorded and released the 1977 EP Spiral Scratch on their own New Hormones label, becoming the first independent UK punk record. By the 1980s, do-it-yourself punk labels had morphed into a global network of music distribution similar to the industrial music labels, pushing recordings directly to the fans, much to the distaste of the established music industry.

Related article:

Meanwhile in London, as punk was rising, Eno was still experimenting with tape loops, layering them over each other to create the four experimental pieces of music that would give a name to ambient music.

In Eno’s biography, On Some Faraway Beach: The Life and Times of Brian Eno, David Sheppard writes that the resulting 1978 album Ambient 1: Music For Airports realised “the full crystallisation of ideas about environmental music that had been implicit in a good deal of Eno’s work since early 1975”.

Although underappreciated at the time – “Eno-esque” even became a term of abuse in the music press – this new experimental music would gain currency in the 1990s, when a new generation of electronic artists would breathe life into the genre.

From punk and hip-hop to industrial and ambient, the cassette tape was ever present in the development of genres in the 1970s.

Dawn of the compact disc

Credited to engineer Nobutoshi Kihara, the Walkman was released by Sony in 1979. The early prototype was seen as an expensive novelty item, but the portable tape player listened to on headphones would bring its own portability revolution in the 1980s, when it would be adopted across the world.

But as this was happening, the golden era of the cassette tape was already ending as a new technology that Otten played a role in developing, the compact disc (CD), launched in 1982.

The CD format would go on to dominate the music industry in the 1990s, leaving tapes and vinyls to the collectors. Sony manufactured the last Walkman in 2010, an announcement that surprised consumers who didn’t realise the company still made them. The last car with a cassette deck also rolled off the manufacturing line in 2010.

Over the cassette tape’s lifespan from 1963 to 1988 more than 3 billion tapes were sold globally, and while it may not be a familiar item anymore, its legacy is still all around us.