Reissued Shihab album sets the record straight

Matsuli Music’s re-release of Ibrahim Khalil Shihab’s Spring, lost or miscredited for more than 50 years, rewrites the history of the music and the jazz artist’s legacy.

Author:

2 December 2020

Ask any South African jazz fan, even a young one, what was happening on the Cape Town jazz scene in the late 1960s and the answer is almost certain to include, if no one else, the name of Winston Mankunku Ngozi. That’s understandable, given the national splash made by the saxophonist’s 1968 debut album Yakhal’inkomo. But it’s also an answer that conceals as much as it reveals, as the latest reissue from Matsuli Music, Spring by the Ibrahim Khalil Shihab Quartet, demonstrates.

The Cape Town scene in the late 1960s and 1970s was crowded and jumping: noisy with unique voices. Clubs such as the Zambezi Restaurant and the Room at the Top were the meeting ground for musicians of all genres: from the Eastern Cape, drawn by greater commercial playing opportunities, from Joburg, drawn by a (temporarily and only slightly) less stringent application of apartheid rules, and from the city’s own townships and suburbs.

Cape Town already had its jazz dynasties. Most famously, there was the Ngcukana family led by its patriarch, baritone saxophonist Christopher “Columbus” Ngcukana. But there was also an upcoming crew of immensely talented brothers, the Schilders. Anthony, Richard and Christopher were pianists, Phillip was a bassist and Jackie played drums. The young Schilders had their first music schooling on the parlour piano from their mother, an energetic and talented composer and pianist for her church.

Born with the music

“She was doing that even when she was pregnant with me. I was born with the music,” remembers Ibrahim Khalil Shihab. Then Chris Schilder, Shihab is now a dignified, snowy-bearded elder who embraced Islam in 1975, 10 years after a revelatory spiritual dream.

When he cut Spring, Shihab was 22 and had been playing in clubs since his mid-teens. He recalls being challenged by a patron to play the challenging changes of the song All the Things You Are, and scoring a huge tip when he succeeded.

On Spring he was ensemble leader, composed all the original material and developed the arrangements. The album should have been a benchmark debut for him, building on both the empathy he and his brother Philly had built in regular gigging together and on the established touring partnership between the other three: Mankunku, guitarist Gary Kriel and drummer Gilbert Matthews.

But since then, until this re-release, Spring has been a constant source of pain.

A subtle erasure

Gallo, which had just acquired the Troubadour label, a rich source of jazz from the era, granted the musicians less than two hours at Johannesburg’s Herrick Studios to record the five tracks. This was despite the fact that all the material was new, except the closer, the standard You Don’t Know What Love Is. Shihab requested time to re-record one track, but Gallo “refused me and put out the album”.

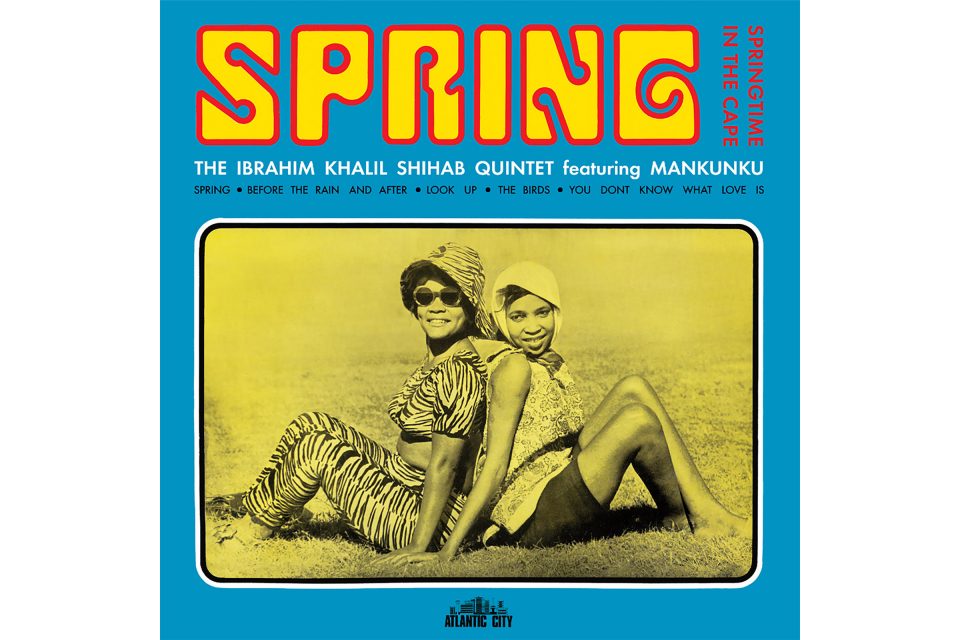

The original album liner notes, by Joburg jazz impresario Ray Nkwe, were long on the Coltrane/ Mankunku comparisons, barely mentioned Shihab’s compositions or pianism and carried the usual slightly patronising tone of Joburg jazz fundis surprised by good jazz from the Cape. The cover image, Drum magazine photographer Ronnie Kweyi’s photograph of two female festivalgoers posed like the logo of then high-fashion sportswear brand Kappa, suggests far more frivolous musical contents.

Then the original masters were lost, allegedly destroyed in the 1973 Steeldale EMI warehouse fire. This was the same fire that consumed all the sales records for Yakhal’inkomo, making it, declared the company at the time, impossible to calculate the royalties due on that release.

Related article:

Spring didn’t resurface until 1996, when Teal Records placed the five tracks as tailenders on a reissue of Yakhal’inkomo, describing it inaccurately as “Mankunku’s second album”.

“I was angry [about that],” Shihab told jazz writer Warren Ludski, “and called the record company, Gallo Music, but could not find anyone to assist me because it seemed as if no one knew anything and I just didn’t bother to pursue the matter. Strange thing is that up to a certain point, about 10 years ago, I was still receiving royalties from the company for that album and it suddenly stopped.”

Setting the record straight

The reissue puts all those wrongs right and has Shihab’s explicit blessing. The liner notes, by University of the Western Cape Centre for Humanities Research scholar Valmont Layne, situate the music and the scene in the unique sonic space of the late 1960s, before the completion of clearances and the intensification of apartheid crackdowns, when a uniquely rich Cape Town cultural scene flourished.

The 2020 remastering provides a sharper, crisper sound, especially noticeable in the way Philly Schilder’s bass comes to the fore. On The Birds, his opening bass drone was barely audible. Now it, and his ensuing sombre walking line and solo, underline the meaning of the song.

Just as Yakhal’inkomo could be dismissed by white authorities as dwelling on the safely rural theme of cattle (when it was actually about, said Mankunku, “the Black man’s pain”), so The Birds is not about birdsong in spring. It’s the one track for which Nkwe’s exegesis in the liner notes gets it right: “Dedicated to the group themselves … it reminds them of the old times when they used to practise from Monday to Monday … nothing to eat or drink but water … when they used to live like birds” – the fate of Black musicians, classified as either “day labourers” or “vagrants” in apartheid labour categories.

On the record, Shihab’s compositions give Mankunku the scope to fly that critics of the era took so much note of. What is less credible is how little note they took of the pianist’s playing. Even at his young age, as he demonstrates on You Don’t Know…, he already had the gift of making you listen to a well-worn tune with completely fresh ears. And his keyboard mastery is dazzlingly fierce.

Related article:

It’s the title track that announces Shihab’s musical character most clearly. It is deeply thoughtful, with his own solo at once melancholy and hopeful. Under apartheid, the concept of spring always carried metaphorical weight for oppressed communities – brighter days had to come – and Mankunku’s searing second solo cries out for them.

Late 2020 is proving a golden period for reissues: Armitage Road and Yakhal’inkomo from Canada’s wearebusybodies label as well as Spring from Matsuli Music. There are more scheduled, including imminent re-releases of the Kippie Moeketsi/Hal Singer Blues Stomping and Movement in the City’s Black Teardrops. Early in 2021, Matsuli plans a double of The Beaters’ Harari and Harari’s Rufaro/Happiness.

All this music banishes some music historians’ dismissal of the late 1960s to late 1970s as the “silent decade” when the only South African jazz worth hearing was happening in exile. The truth is, the music sounded loud, but the record – literal and metaphorical – was too often erased. Spring, like the others, rewrites the history much closer to how it really sounded. And it’s beautiful.