Album Review | We Are Sent Here By History

The new album by Shabaka and The Ancestors is a meditation on history, and asks its listeners to imagine new modes of being.

Author:

31 March 2020

In 2013, British jazz group Sons of Kemet released their debut album, Burn. Fronted by the British-Barbardian saxophonist Shabaka Hutchings, the album opens with its fists raised.

The song All Will Surely Burn, which features menacing percussion and a screeching tuba, set the album’s high-paced tone. Half-seance, half-ambush, the album was equal parts musical statement and political declaration: “We have come here to fuck shit up”.

Seven years after its release, Shabaka Hutchings can see the end of the world ambling into view.

“It’s a strange time,” says the saxophonist over Skype. “With the global pandemic [Covid-19] especially, no one knows what the world will look like in a few months. I don’t know how the situation is playing out in South Africa, but the response has been pretty pathetic in the UK. But endings aren’t always the worst thing to happen. They signify the birth of something new.”

Related article:

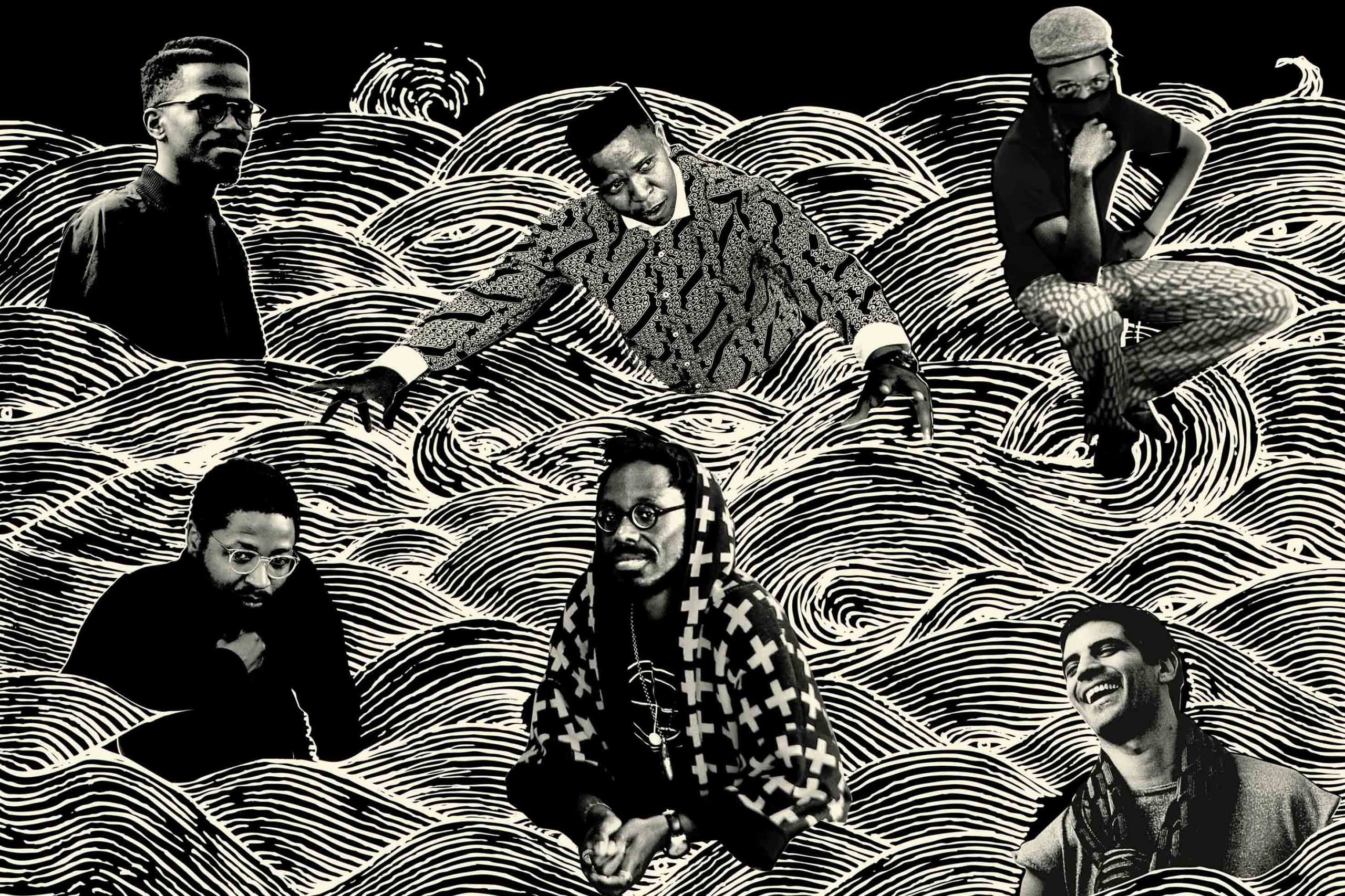

Hutchings is a purveyor of forward-thinking cosmic jazz. He’s also a man whose artistic output seems to know no end. Though he has no solo album, in the last seven years, he’s released 10 projects through the bands he’s part of: Sons of Kemet, Shabaka and The Ancestors and The Comet is Coming. Shabaka and The Ancestors is a cross-continental octet with South Africa-based jazz musicians Mthunzi Mvubu, Mandla Mlangeni, Siyabonga Mthembu (vocals), Nduduzo Makhathini, Ariel Zamonsky, Gontse Makhene and Tumi Mogorosi.

Recently, the band released their second album, We Are Sent Here by History. A collection of “sonic poems”, the 12-track album is a meditation on what history has collectively wrought on the body and how it is possible for us to move forward. And like Burn, its thematic precursor released with Sons of Kemet, the answer lies within the fire.

Considering history

According to Hutchings, history can’t be redeemed or revisited. It needs to be burnt completely.

“The title came up during conversations [the band] had while recording it. It alludes to the circular state of history and the idea that it’s bound to repeat itself. There’s something to be learned from that. The present was calculated by the events of history. The album is about what needs to be burned and what needs to be redeemed.”

The album opener, They Who Must Die, opens with scattering drums and a dizzying saxophone. It’s here where the band’s vocalist Siyabonga Mthembu incants the album’s title. “We are sent here by history,” he shouts before mapping out a set of instructions such as “burn the archive, burn the student loans.”

Related article:

Mthembu’s vocals mirror the poetic rage expressed in the liner notes of the group’s debut album, Wisdom of Elders. Written by South African writer and feminist thinker, Lindokuhle Nkosi, part of the notes read: “In the burning of the Republic, it is always the flattened mountain that performs the first act of self-immolation… Fire in the peripheries we’ve been relegated to. Queer black bodies spinning on the tip of a candle-flame.”

The liner notes served as a palimpsest for all of Mthembu’s vocal contributions across the album, as their words act as layers of ideas that are constantly reinscribed, in constant conversation.

“It’s a simple process,” says Hutchings of the album’s recording. “I wrote [the composition of] the album and tried to map out what it could look in terms of structure. But everything percussive and vocal is all interpretive. I don’t tell Siya what to write. His vocals are an interpretation of the music I’ve written. For this album he read the liner notes of Wisdom of Elders. His vocals are a conversation with that text. It speaks of the burning.”

You’ve Been Called, the album’s second track, dials up the ante. “An act of destruction gave birth to creation,” Mthembu muses in his characteristic blank verse, this time sitting under a twinkling key section that echoes into a phantasmal blackness. “We possess the power to pray our devils back to hell, back to the burning.”

The album’s middle chapter, with the songs Go My Heart, Go To Heaven; Behold, The Deceiver and Run, The Darkness Will Pass, sees the band turn heavenward to confront the unbearable heaviness of being. When the band is in full swing, the maximalism can feel a bit overwhelming, but this is always followed by moments where double bassist Ariel Zamonsky quietens the pace with his solo riffs.

New modes of being

Ultimately, We Are Sent Here by History asks its listener to imagine new modes of being. It asks what a new world – one that doesn’t carry the freight of history – would look like. For South Africans this might be a particularly hard exercise to partake in. Part of being South African is being married to myth. We’re a country attached to the idea that broken things can be rehabilitated. The idea is impressed on you so repeatedly – through Rainbowism and appeals for a new non-racialism – that you actively have to train yourself to resist the impulse.

But, if We Are Sent Here by History proves anything, it’s that death predates rebirth. Some things can’t be rehabilitated.

“The beginning of everything is also the end of things,” says Hutchings. “It’s an opportunity to reassess what needs to be saved before we can move forward. That’s why the first track begins with the end of things; it’s a proclamation where we introduce the idea of birth and rebirth.”

The album’s final quarter is dedicated to the end of masculinity (or, the kind society is currently invested in). We Will Work (On Redefining Manhood) opens with a flute section and vocals from Mthembu that translate to: “A man does not cry, a man does not grieve”, before ending with the refrain, “manhood is difficult, we will work on redefining moment”.

Related article:

Two songs later, there is release. There is a palpable sense of relief in Mthembu’s voice when, on Finally, The Man Cried, he shouts the song’s title over and over again. The moment runs through to Teach Me How To Be Vulnerable, the last song of the album. Here, the song’s sentiment is carried strictly by its atmosphere (there is no vocal contribution from Mthembu) but, even then, there’s a meditative energy to the sparkling keys and languid tuba rhythm.

Sure, invoking the “men don’t cry” line as a critique of masculinity does come off as cliché. But in an album that dares us to re-imagine ourselves into new worlds, our collective thinking of what shapes masculinity is the cliché.

Related article:

“When the album was being conceived, masculinity and the weight of it was on my mind. A lot of the zeitgeist and conversation was about patriarchy. Not just in South Africa but across the border with the Me Too movement. A fundamental aspect of any utopia would mean a reassessment of masculinity. If you want to reframe the structure, you’d have to reframe what it means to be a man, a woman.”

We Are Sent Here By History is an album of hard questions and no easy answers. Shabaka and The Ancestors ask what it means not just to interrogate history but to reckon with it honestly. History may have brought us here but, over the band of dawn wrapping itself across the horizon lies the promise of a history that cannot be maimed or stolen. Perhaps, this persuasion – and, indeed Shabaka and The Ancestor’s call to action – is best described by a few lines from American poet Danez Smith’s poem, Dear White America:

“I am giving the stars their right names.

& this life, this new story & history you cannot steal

or sell or cast overboard or hang or beat or drown or own

or redline or shot or shackle or silence or impoverish

or choke or lock up or cover up or bury or ruin

This, if only this one, is ours.”