Rugby needs to polish its image

SA Rugby’s response to the serious allegations levelled against Eben Etzebeth and his participation in the Rugby World Cup have taken the shine off the Springboks in Japan.

Author:

11 October 2019

Sport is a powerful tool for social cohesion, but in the hands of the wrong people it can be extremely divisive. South Africa knows this better than any country. Sport has brought South Africans together and it has also divided them.

The apartheid government used sport to divide the nation, whether through investing in world-class infrastructure in white neighbourhoods while spending peanuts on black people or the make-up of the teams that represented South Africa during those days, when an athlete’s skin colour rather than their talent earned them a place.

Rugby was at the heart of this division and apartheid itself. Both the ruling party at the time and those fighting to end the oppresive regime called the team the “ambassadors of apartheid”. The Springboks were a symbol of oppression and a bastion of Afrikanerdom. When all other sporting codes were kicked out of the international arena because of South Africa’s racist laws, rugby remained unaffected until the national team’s tours to England (1969), Australia (1971) and New Zealand (1981) were met by protests.

It wasn’t surprising to see calls for the springbok to be dropped as the symbol of the national rugby team after the country’s first democratic election in 1994. Those calls were met with strong opposition from white quarters, especially those who weren’t too pleased with this democracy business. Former president Nelson Mandela called for a compromise; the springbok would stay, but as a symbol of all South Africans.

The Rugby World Cup victory on home soil in 1995 went a long way in making the team and the springbok a symbol for all. But Mandela’s reconciliatory tone – his charming nature and the high of winning the World Cup – papered over the cracks, it didn’t fix the underlying problems. Once Mandela’s hypnotism and the World Cup high wore off, reality sank in.

Related article:

The underlying problems were still there. The government still did not do enough to improve infrastructure in township schools so as to debunk the notion that the Springboks belonged only to players from posh schools, who continue to make up the bulk of those who have worn the green and gold.

That’s why a player like Makazole Mapimpi is so important for the transformation of rugby in the country. The Jim Vabaza Senior Secondary School product became a Springbok, going on to represent his country at the World Cup. And he did this against all odds, because he didn’t go to the elite schools with their well-paved paths to the national team.

The Eben Etzebeth conundrum

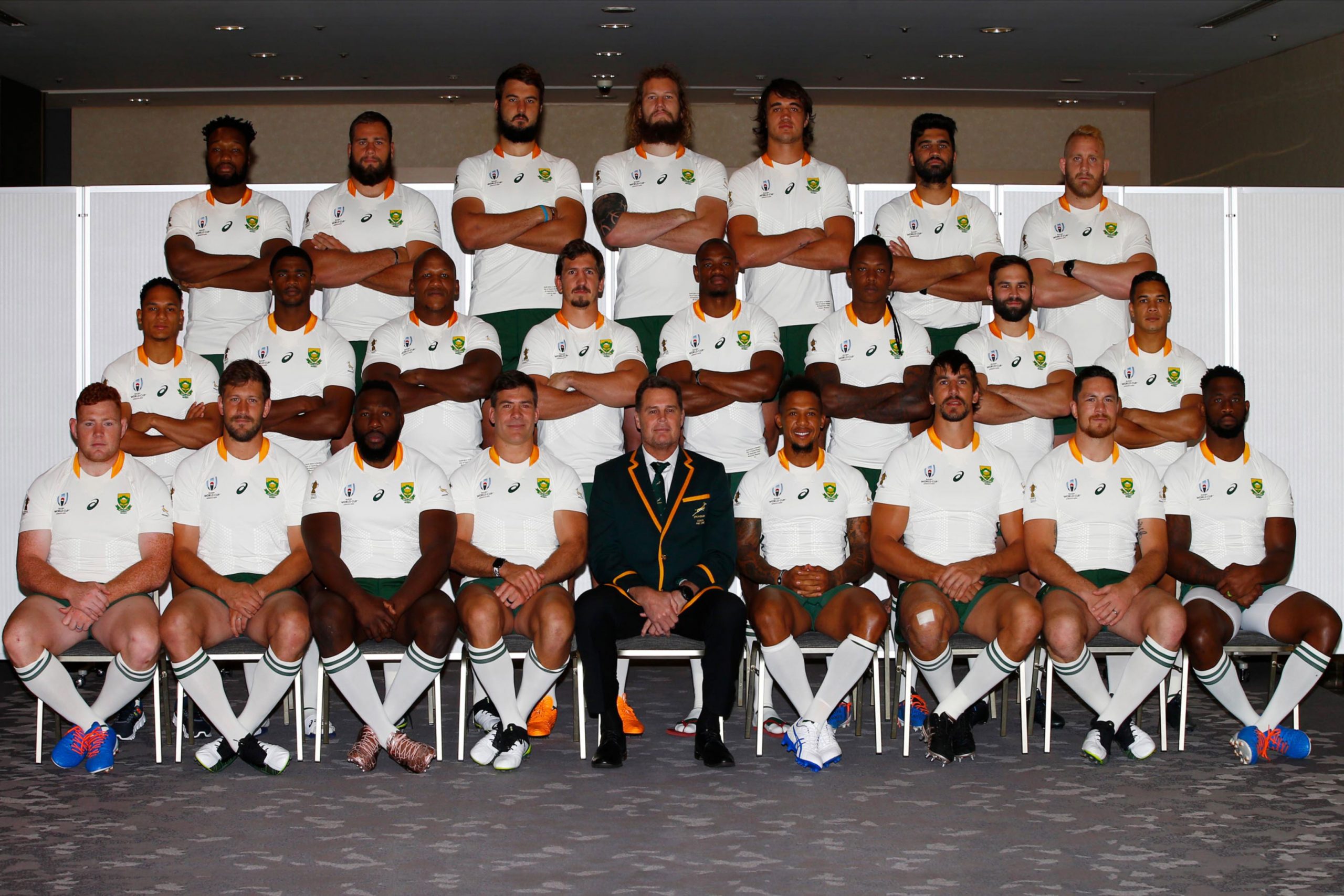

His story and that of Siya Kolisi, the first black captain of the side, is a cause for celebration and what we should be talking about in terms of the global showpiece being played in Japan. But the story that has dominated Bok talk is that of lock Eben Etzebeth, who is alleged to have physically and racially abused a homeless man in Langebaan in the Western Cape.

The South African Human Rights Commission has taken the matter to the equality court on behalf of the four men categorised as coloured during apartheid who were allegedly involved in the altercation. They have accused Etzebeth of assault, wielding a firearm and hate speech. The news of the alleged assault broke in August, just before Etzebeth and the Springboks flew to Japan for the World Cup.

But his place in the squad and involvement in the tournament were never in doubt. At first SA Rugby remained mum on the matter, naively hoping that a good run at the tournament would dampen the fires of anger these accusations caused. But the more they remained silent, the louder the matter became.

SA Rugby initially said it was allowing the law to take its course, and then later said it was undertaking an internal investigation when the issue began battering its image. When it comes to matters of principle, though, this is not a sport known for doing things of its own accord, having shown little regard for principles in the past. So it’s difficult not to view the “internal investigation” as merely a way for SA Rugby to look as though it is doing something.

It was a missed opportunity for South African rugby to work on its image. Worse, it set a dangerous precedent, which suggests there are people who are beyond the badge.

“What if it transpires in a few weeks that the player is actually innocent? He can take us to the cleaners. We have to protect the organisation,” SA Rugby president Mark Alexander told the Sunday Times newspaper when asked why the organisation hadn’t kicked Etzebeth out of the team so he could return to the country and clear his name. The publication went on to report that Etzebeth is allegedly part of a group of men called the Wolf Pack that is notorious in Langebaan for its thuggery.

Perception of untouchability

It’s highly unlikely that Etzebeth would be at the World Cup with these serious allegations looming over his head had he not been a high-profile player and a vital cog in coach Rassie Erasmus’ ambitious World Cup plans. This stance further supports the notion that athletes are untouchable, especially talented ones.

Related article:

While SA Rugby and Erasmus are not breaking any laws by fielding and backing Etzebeth – he is innocent until proven guilty – they are sending the wrong message in a team that already has a reputation problem. The seriousness of these accusations makes SA Rugby’s decision to keep Etzebeth in the team, remain quiet and hope they’d go away ill-advised. The fact that Etzebeth is white and his accusers are black also makes this worse in a racially sensitive country.

Already contending with their racist past, the Springboks seem to consistently make it more difficult for everyone in the country to support them. Being an inclusive team with country-wide appeal means not being afraid to make bold decisions when key players drag their reputation through the mud.

Fuel to the fire

The Bomb Squad fiasco, in which a group of white players looked to be ignoring Mapimpi, was a storm in a teacup. It was a simple matter, the bench doing their traditional huddle and taking the piss out of Lood de Jager, who started against Italy and therefore forfeited his place in the Bomb Squad, the name given to matchday replacements. But the short video looked bad without context, ruffling the feathers of South Africans of all colours. Even though it was an innocent act, it was tough to give the team the benefit of the doubt because of the issues around race and privilege that still prevail.

This is why it is imperative that SA Rugby consistently does the right thing, to fix the Springboks’ image problem. Those in charge need to show leadership in troubling times instead of burying their heads in the sand.

That the Springboks and the World Cup tournament are only watched by a privileged few doesn’t help rugby’s image either. It’s understandable why SA Rugby signed with major satellite service MultiChoice and its array of pay-television channels; the broadcaster has the funds to keep it and the game afloat. But as most South Africans aren’t able to watch the national team play on a consistent basis, they are isolated from it and the sport is inaccessible to most households.

Adding to this, the SABC’s financial woes threatened its broadcast of World Cup games. It reached a last-minute deal with World Rugby to air a handful of matches, a dismal attempt to bridge the huge disconnect between the majority of South Africans and rugby.

And then there are stadiums in which the crowd only really sings Die Stem part of the national anthem, so the stadium experience is still not inclusive either.

The sport has made admirable strides since the days of apartheid, but it’s not enough. The Springbok’s tarnished image has to be fixed, and it’s going to take strong leadership and tough decisions to make the team truly South Africa.