Sacred facts and lies, damned lies

In Text Messages this week, Piet Rampedi would have done well to heed early historians Herodotus and Thucydides – arguably the first foreign correspondents – when it came to his decuplets story.…

Author:

1 July 2021

It’s a reflex for journalists to describe their craft as “the first draft of history” and it was a journalist who first defined it thus. Philip Graham, who went on to become the publisher of The Washington Post, said “journalism is the first rough draft of history and earning my history degree gave me the skills that I use as a journalist every day”.

The tie-in with history is significant. Both disciplines seek to establish who did what to whom when, where, why and how. History, with the perspective of hindsight and the luxury of time, has it easy in some respects because the journalist must deal in the moment with the complex and confusing unfolding rapidly and with the insistent background demands of a news editor and news machine.

Related article:

At the core of both is the search for truth, often misrepresented as “objectivity” or “impartiality”. The thing to which the historian and the journalist should be partial is the truth and yet, all too often, both run into Mark Twain’s conundrum: “There are lies, damned lies and statistics.” A striking contemporary instance of this is the case of the “Rampedi Ten”, the 10 babies alleged to have been born to a single mother in Gauteng, South Africa.

Despite the creator of the story, Pretoria News editor Piet Rampedi, standing by it, the tale has been not only widely derided but also proven false by careful scrutiny of hospital records and other medical data. For a while, though, it captivated sections of the media globally and nationally as well as large parts of the public. After all, decuplets – 10 babies in a single delivery – constituted, among others, a potential entry in the Guinness Book of World Records.

Facts are the oxygen of journalism and history. Not for nothing did legendary The Guardian editor CP Scott declare that “comment is free … but facts are sacred”. When the facts didn’t stack up in the decuplets story, it collapsed. Like fossil hunters, the historian and the journalist go fossicking for facts, ferreting for untruths. It is exhilarating and exhausting and, properly done, personally fulfilling and rewarding for society.

Related article:

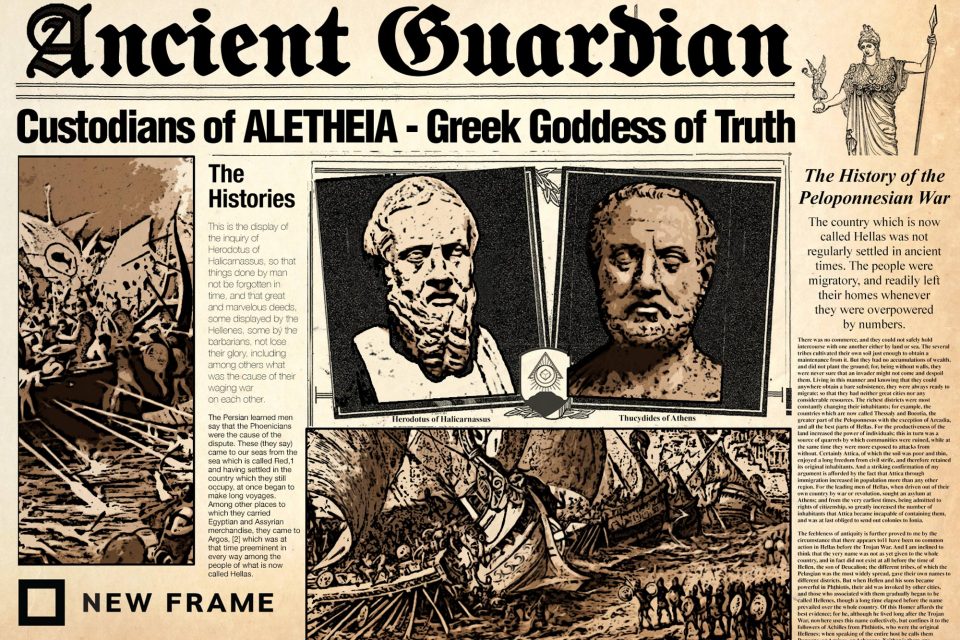

The first historian is deemed to be Herodotus of Halicarnassus, who lived from 490 or 480 BCE to 425 BCE. Herodotus is known as the Father of History because his work, The Histories, laid down an approach to establishing, recording, analysing and writing about facts. In essence, he founded the discipline of History, though he was and sometimes still is scurrilously and unfairly dubbed “the father of lies”, which shows the contours of the debate around evidence, fact and verifying those.

Herodotus combined a searching interest in the people, animals, plants and happenings in the world around him: you can view him also as a travel writer and keen anthropologist, the latter shown by his fascination with all manner of human customs in the lands he visited. Tom Holland, the eminent classicist, said that Herodotus was arguably the world’s first foreign correspondent, given his acute awareness of politics, geopolitical strategy and warfare.

Searching for answers

The very first sentence of The Histories is a masterpiece of conciseness. Here it is, in Aubrey de Sélincourt’s translation.

“Herodotus of Halicarnassus, his Researches are here set down to preserve the memory of the past by putting on record the astonishing achievements of both our own and of other peoples; and more particularly, to show how they came into conflict.”

Conflict between the Persians and the Greeks is the great theme of The Histories, and Herodotus records and orchestrates it with all the verve and versatility of the first historian, the travelogue writer, the social anthropologist and, yes, the best of foreign correspondents, ever inquisitive, questing, searching for answers.

Related article:

Thucydides (circa 460 BCE to 400 BCE), the second great historian, considerably refined and extended Herodotus’ pioneering historiographical methods and theories. The result, The Peloponnesian War, tells of the conflict between Athens and Sparta that began in 431 BCE and ended in the defeat of Athens in 404 BCE. It is both profound history and ground-breaking international relations text, the first of its kind. The great classical scholar Moses Finley summed it up best:

“Further, Thucydides paid Herodotus the even higher compliment of grasping and accepting, as virtually no other contemporary had done, the great discovery the Father of History had made, namely, that it was possible to analyse the political and moral issues of the time by a close study of events, of the concrete day-to-day experiences of society, thereby avoiding the abstractions of the philosophers on the one hand and the myths of the poets on the other.”

No better credo exists for those writing both the “first rough draft of history” and history itself.