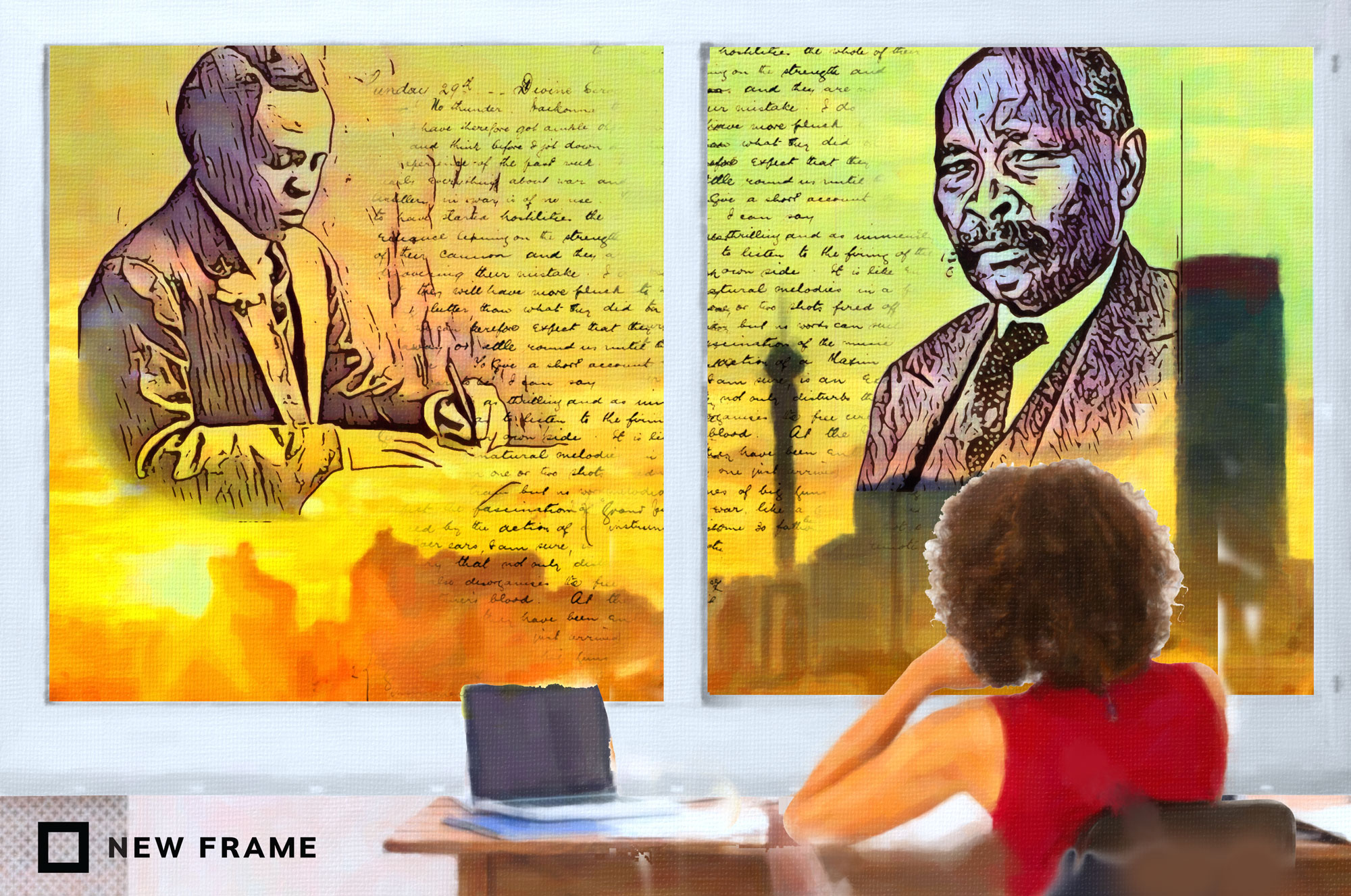

Salute the ANC’s original thinkers

The roots of many achievements of the party were laid down by leaders whose writing captured not only the essence of the time but contained lessons and warnings for the future.

Author:

14 January 2021

As the ANC celebrates the 109th year of its existence, it is a rebuke to the present to recall the intellectual and literary calibre of its early leaders. Let us take but two: John Langalibalele Dube and Sol T Plaatje.

Dube was elected the first president of the South African Native National Congress, later to be the ANC, in 1912. It was he who led the congress deputation to London in June 1914 to make the case against the previous year’s Native Land Act, by which Blacks were dispossessed of land and traditional agrarian rights such as sharecropping. Plaatje was the secretary on that mission.

But Dube’s tenure as president was relatively brief, ending in 1917 because of leadership disagreements. Thereafter he was an adviser to the Zulu royal house of King Solomon and continued editing, until 1934, the newspaper he had founded in 1903, Ilanga lase Natal (The Sun of Natal), a bilingual weekly in isiZulu and English.

Dube also devoted himself to literary work, including biography, pamphleteering and translation, the last including helping FL Ntuli with the rendering into isiZulu of H Rider Haggard’s Nada the Lily (1892; translated as Umbuso kaShaka and published in 1930). Before the politics, he had taken part in the seminal Durban conference of 1907 that met to agree on and set up a standard spelling system for isiZulu.

Related article:

Perhaps Dube’s outstanding literary achievement is authoring the first novel in isiZulu, U-Jeqe, Insila ka Tshaka (1930, Marianhill Mission Press), which was to be translated and published in English five years after he died in 1946. Translated by J Boxwell, Jeqe, the Body-servant of King Shaka was published by Lovedale Press in 1951. The great scholar DBZ Ntuli summed up its importance, saying, “All agree that it is one of the permanent classics of literature in the African languages.”

A historical novel crossed with the story of Jeqe’s personal and spiritual growth, Insila kaShaka (as it is frequently abbreviated) also offers a glimpse of the tensions at play in Dube, simultaneously a respecter of tradition and a Christian. His hero, Jeqe, leads a remarkable life of two acts. After the death of Shaka, Jeqe flees the reign of Dingane and his motherland and makes a new life for himself, the body-servant transforming into a healer. Jeqe of the Buthelezi clan becomes Mshayikazi Mcunu, doctor to the Swazi king.

A profound thinker

Dube’s shipboard companion on that long journey to London, Plaatje, is the more versatile literary figure and more profound thinker. It is thanks to his Native Life in South Africa that we have an acute idea of the land thefts, uprooting and evictions that followed in the wake of the Native Land Act of 1913, and the terrible personal consequences for those so brutally displaced.

Plaatje’s writings show the personal as the political as the literary. That unwavering line is brilliantly drawn by the late literary scholar Tim Couzens in his introduction to the landmark Heinemann African Writers Series edition (1978) of Plaatje’s famous novel Mhudi: An Epic of South African Native Life a Hundred Years Ago (1930, Lovedale Press).

Couzens writes: “The most crucial preoccupation of Plaatje’s throughout his life, however, was the question of land distribution …

Related article:

“It is my contention that Mhudi is not only a defence of traditional custom as well as a corrective view on history, but it is also an implicit attack on the injustice of land distribution in South Africa in 1917. Native Life and Mhudi must have been written very close to one another in time: in fact, between pages 105 and 111 of the former book the whole background story of Mhudi is contained.”

Couzens notes that Plaatje chooses the 1830s, when Mhudi is set, as a model for South Africa after 1913. “What happened in the 1830s might happen in the twentieth century, only to different oppressors. Plaatje is sounding an implicit warning: he is not advocating revolution – merely indicating its inevitability if certain conditions continue to prevail.”

Those conditions carried on, in ever crueller and more defined, categorised and limiting ways. Apartheid gave way to the grand apartheid of Verwoerd and then to the inevitability of revolution as the ANC, through pressure from abroad and the internal resistance of the United Democratic Front, brought a different South Africa into being.

It must not be forgotten that many of the roots of that achievement were the work of two writers – journalists, editors, essayists, pamphleteers, translators, novelists and political writers – John Langalibalele Dube and Sol T Plaatje.