Shifting vinyl with my grandfather’s records

The older generation collected music, whereas today’s aficionados collect records. Vinyl has become an art object, and fanatics scratch through family albums for that next gem.

Author:

1 April 2021

I have a thread of memories of sitting outside the scorching heat of my grandmother’s house in Durban, catching some shade under the mango trees with my grandfather. I would sit next to him, watching his slow, coarse fingers roll tobacco. At times he would sprinkle some marijuana in, smoking this with head bobbing as if he were chasing a particular groove only he could hear. Vinyl records were playing.

None of our conversations ever touched on vinyl as a medium. He would only ever dwell on the sounds, places, eras and communities of people who shared his affinity for music. We would have our first conversation about vinyl when I started collecting records. It then dawned on me that we entered this exchange from very different perspectives.

My grandfather started collecting records simply because that was the way music was sold at the time. The joy wasn’t necessarily in the discovery of a rare album but in the intimacy of hearing the shape of sound unfurl. He developed a friendship with sound – a space where music gathered the parts that apartheid tried to render unconscious through its humiliating effects.

I am weary of the term “collector” when referring to his relationship with vinyl because of how it signifies a direct objectification of sound as something to own in a way that does not accurately account for his sensibilities. He does not treat records as art objects that overtake the actual music. His collection forms alongside a spontaneous approach to the music. Like many of his peers, he wasn’t collecting to complete catalogues but instead treated music like a dancer who likes to keep his head bobbing while absorbing everything across traditions, borders and seas. He was chasing a particular sound and energy more than a genre, name or collection.

Related article:

In his collection, you will find rare South African funk classics such as Almon Memela and Masike “Funky” Mohapi, Johannesburg messengers such as The Soul of the City, jazz luminaries such as Winston Mankunku and Abdullah Ibrahim, and African-American sounds from Isaac Hayes, Gene Ammons and others. His collection is like an old tree with deep roots and many branches of sound.

I share an affinity with him insofar as chasing sound over catalogues is concerned. My collection of Global South eclectic sounds, from Morocco to Suriname, is an expression of his approach. But we diverge when my art-collector sensibilities take over and the provenance of records takes precedence. Vinyl takes on a spatial life in which emphasis is placed on cultural histories and “scarcity”. For instance, there is excitement in finding records from the Left musical traditions in Chicago, Boston, Detroit and Los Angeles through people such as Phil Cohran, Bubbha Thomas, Lon Moshe and Horace Tapscott.

Vinyl collectors

For collectors of a younger generation, curiosity is still the organising principle but the movement of time, shifts in resources and market conditions shape how this curiosity manifests itself.

Vinyl collector and cofounder of Fly Machine Sessions Vusi Hlatywayo agrees. “We are looking for things that are not easy to find,” he says. He raises the point that my grandfather’s generation has no idea of the context of these records today. “They don’t know if [they are] rare or if there is a scarcity because they [bought] these records at the time of their release.” For some people, finding a record is an extension of their relationship to the music of an artist, movement or tradition. The rarity of certain original vinyl pressings means some collectors choose to buy reissues to manage the inevitable wear and tear on original releases.

-

30 March 2021. Vusi Hlatshwayo. Picture: James Oatway. -

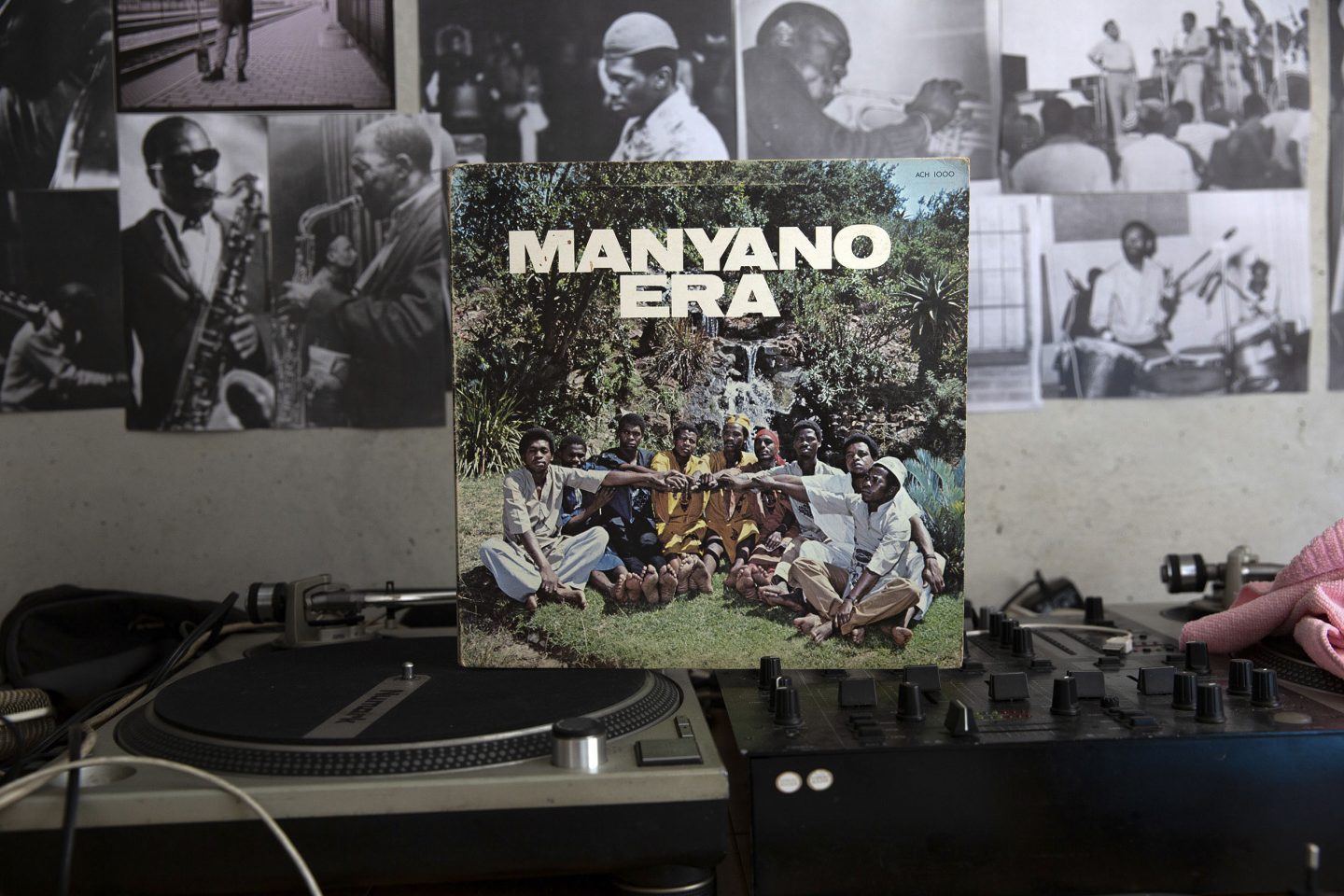

30 March 2021. Manyano Era LP owned by Vusi Hlatshwayo. Picture: James Oatway.

Durban-based record collector and member of the eThekwini Jazz Appreciation Society Mamsie Ntshangase grew up listening to her parents’ music. Her love for vinyl is a combination of community and history: “It is also the appreciation for the longevity and timelessness of the music, the pleasure of reading liner notes and, of course, the magnificent artwork on the sleeves. Those always make for interesting talking points during listening sessions.”

As a woman collector, Ntshangase faces prejudice. “When I started working, earning and spending money collecting, I was shocked to experience high levels of chauvinism and being patronised by males who did not understand what I was doing in what they regarded as ‘their world’, as they put it. Even when presenting a set at a listening session, I would be told that I ‘play like a man’, or [asked] ‘how come I know about such and such an artist’.”

A slow process

Notable collector Sakhile Ndlazi, known as DJ Bubbles, began collecting vinyl with hip-hop: “The first record I bought was a DJ Jazzy Jeff & Fresh Prince He’s the DJ, I’m the Rapper LP, and because they were sampling, I started checking out those records that they were sampling. Some of these records were already in the house [his parents’ home].” Later he collected house music. “In the 1990s it was still affordable. You could get an international record for 30, 40 bucks. That was my lunch money. I wouldn’t eat at school knowing come end of the week I [was] getting a record.”

My grandfather’s buying practice attests to a similar slow process. He would come back with one or two records on weekends. As a factory worker paid weekly, his mode of subsistence and proximity to wage labour guided his purchasing. If he didn’t have a particular record it didn’t matter because one of his friends would have it and share it at their listening sessions in KwaMashu and Umlazi section N townships in Durban in the late 1970s and 1980s.

For Ndlazi, collecting has always been a family affair. “I’m from a family of collectors – both my mom and dad were collecting records,” he says. Similarly, Hlatywayo says, “I started with my uncle’s collection. I took it, then started digging [through his family’s collections] house to house.” Through this process he found South African gems such as the Manyano Era.

His vast collection of South African music is a labour of love: “Once I found that dead stock record goldmine, I became more aggressive with [record digging], looking for secondhand shops [and] looking through telephone directories to locate old shops.”

For Ntshangase, record collecting is about “passion, curiosity and impulse”. Hlatywayo agrees about curiosity playing a big part, along with wanting to sample and flip sounds. “There are specific labels that I trust,” he says. “I’m looking for more funky, organ and guitar-based sounds.” Ndlazi’s approach is motivated by timelessness. “I kind of want to collect stuff that will stay – timeless music, not just to have thousands of records taking up space.”

My grandfather cannot relate to my excitement about his collection because he is loyal to the music itself and not to the form. The meaning of vinyl has shifted because of faster patterns of consumption, a growing market for vinyl art objects and a curiosity and excitement about records. But across generations, connected through sound and memories – like sitting under mango trees – the form endures.

-

17 March 2021. Nombuso Mathibela. Picture: James Oatway.