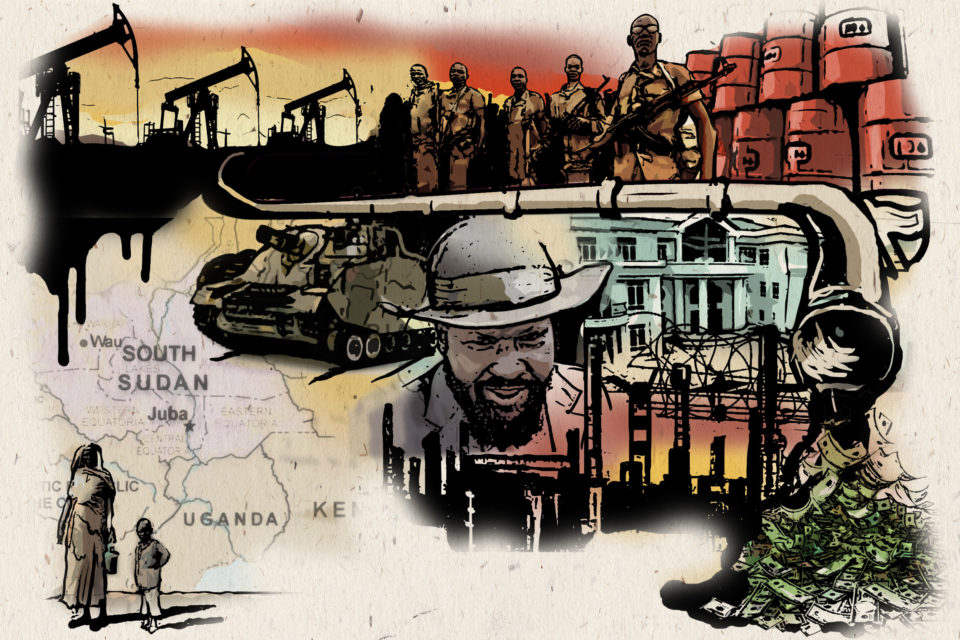

Should SA invest in South Sudan’s oil industry?

South Sudan wants its oil sector back on track, but a report says those doing business with the country risk being linked to corruption and human rights abuses.

Author:

18 February 2019

A proposed deal that would see the South African government investing $1 billion (about R13.7 billion) in the South Sudanese oil sector could see the state in bed with a South Sudanese oil company that is at the heart of recent corruption and human rights abuse claims.

These allegations include Chinese arms deals, the funding of non-state militia, suspect banking practices and oversight, and expensive luxury houses built or acquired by South Sudan’s elite in Uganda and Ethiopia.

As a recent report stated, international companies, traders and lenders doing business in South Sudan risk being linked to atrocities and serious human rights abuses.

Related article:

Minister of Energy Jeff Radebe and his South Sudanese counterpart, Petroleum Minister Ezekiel Lol Gatkuoth, announced in November, the day after Africa Oil & Power’s three-day South Sudan Oil & Power 2018 conference in Juba, South Sudan, that the South African and South Sudanese governments had signed an initial agreement regarding the proposed investment.

They said the deal involved building an oil refinery that could produce 60 000 barrels a day, a pipeline to export Sudanese oil, the training of workers and engineers and exploration rights for several oil blocks.

The ministers said their state-owned entities, South Africa’s Central Energy Fund (CEF) and South Sudan’s Nile Petroleum Corporation (Nilepet), would now conduct detailed negotiations.

Oil firm PetroSA, part of the CEF, would be the obvious South African partner for Nilepet, but the parastatal is in a dire financial position after years of big losses and failed investments. It has been the source of many allegations of corruption, too.

PetroSA rocked local politics when it declared a R14.6 billion loss for the financial year 2014-2015, owing to a failed offshore gas project in Mossel Bay known as Ikhwezi.

In September last year, the auditor general expressed doubts about PetroSA’s financial future.

The energy ministry, Department of Energy and CEF did not respond to questions from New Frame.

Capture on the Nile

A report by global transparency organisation Global Witness, titled Capture on the Nile and released in the middle of last year, alleges that South Sudan’s “predatory elites, who were at the heart of the country’s brutal civil war”, have captured Nilepet.

The report alleges that President Salva Kiir and his inner circle are calling the shots.

Nilepet was established in 2009 to handle the state oil resources, but it is set up as a private company and does not make its accounts public. The Global Witness report says it is “almost entirely unregulated”.

It alleges that funds from the petroleum company are being used to fund the work of the country’s Internal Security Bureau and to arm militia in certain parts of the country.

The report details oil advances that Nilepet has received from foreign companies. An oil advance is payment made for oil that has not yet come out the ground.

The Global Witness report states that as of March 2016, the oil company had received more than $3 billion in oil advances from national oil and gas company China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), Chinese state-owned arms manufacturer Norinco and Geneva-headquartered commodity trader Trafigura.

The report also details 2015 loans from the Qatar National Bank ($790 million) and Kenyan bank Stanbic Holdings ($200 million).

Global Witness says the cost of these debts will continue to affect South Sudanese citizens for a long time.

South Sudan’s GDP averaged $12.88 billion in the eight years to 2016, when it plummeted to $2.9 billion. This means the oil advances represent more than 100% of the country’s current GDP.

South Sudan ‘Untouchables’

A few months after the Global Witness report came out, independent Kenyan media house Africa Uncensored launched an investigative documentary titled The Profiteers. The documentary explored the links between government, business, banks and the military in South Sudan, Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia.

It exposed an arms shipment – including 45 assault tanks, grenade launchers, assault rifles and pistols – that the South Sudanese government sourced from Norinco, the same company that has loaned the government almost $2 billion against future oil supply.

The Profiteers expanded on the work of a group of Kenyan bloggers, who began in mid-2018 to post photos and details about houses the South Sudanese elites own.

These included a lake house in the resort town of Debre Zeyt in Ethiopia, reportedly belonging to Kiir, and a home in Kampala, Uganda, owned by former South Sudanese minister of petroleum Stephen Dhieu Dau.

United Nations reports identified Dhieu Dau’s office in the funding and supporting of non-state militia with oil revenues during the South Sudanese civil war.

The Kenyan bloggers used the hashtag #SouthSudanUntouchables in their tweets.

Standard Bank

The Profiteers also featured findings from investigations conducted by The Sentry, a team of policy analysts, regional experts and financial forensic investigators co-founded by actor George Clooney and anti-corruption activist John Prendergast.

The Sentry turned the spotlight on to Stanbic Holdings, a Kenyan subsidiary of South Africa’s Standard Bank that went by the name CfC Stanbic Holdings until 2016. The bank was formed as the result of a 2007 merger between Stanbic Bank Kenya and CfC Bank.

The Republic of South Sudan became Africa’s 54th nation on 9 July 2011. The following year, Stanbic Holdings opened a subsidiary in Juba, South Sudan. It was the third Kenyan bank to venture into the new nation.

At the time, Stanbic managing director Greg Brackenridge spoke of the “strong and long relationship” the bank has with the people of South Sudan and its government. He said the bank’s investment there was “a vote of confidence” in the country’s future.

Kiir‚ who attended the opening‚ said the decision by Stanbic to invest in South Sudan was timely to help develop the financial services sector in the country.

However, a recently obtained auditor general’s internal audit of South Sudan’s central bank allowed The Sentry to reveal that $669 million was deposited with Stanbic Bank in 2012, the year it launched its new subsidiary.

The Sentry said this was roughly 95% of South Sudan’s foreign cash reserves at the time, despite the fact that the South Sudan central bank by law was not allowed to hold more than 15% of its reserves with another bank.

The Sentry said the audit report concluded that there was “no evidence” that South Sudan’s central bank ever received interest payments that would have accrued as a result of the deposit, which would have been worth nearly $1 million.

‘Business the right way’

Stanbic Bank Kenya, responding to questions from New Frame, said it abided by all laws and regulations in Kenya and South Sudan.

“Stanbic Bank is guided by the mantra of doing the right business the right way,” it said. “We do appreciate our role in this regard both regionally and internationally, and make every effort to meet our obligations.”

“As you may appreciate, we are guided by the principle of confidentiality, which prohibits us from responding on specifics touching on our customers,” said Stanbic Kenya.

In the Global Witness report, it was revealed that Nilepet was a Stanbic customer when commodity trader Glencore paid South Sudan’s ministry of petroleum and mining for Dar Blend crude oil cargoes by depositing money into a Stanbic Bank account in South Sudan that listed Nilepet as the beneficiary.

State of play

South Sudan has estimated oil reserves of 3.5 billion barrels, with just 30% of the country explored. This makes its oil reserves the third-largest in Africa.

However, the country does not have a refinery and exports its oil by pipeline to Sudan. It then has to import refined fuel on trucks, which travel from Kenya’s port of Mombasa, through Uganda and into South Sudan.

Projects to build pipelines in Uganda and Kenya are under way, which could provide an alternative distribution route for South Sudan. But these pipelines take years to build and analysts say there is a pipeline backlog in East Africa at the moment.

Being wholly dependent on neighbouring Sudan, it’s only natural that the South Sudanese government has described a new pipeline as “instrumental”.

Oil production has fallen by more than half since the onset of civil war in 2013, from highs of 350 000 barrels a day to about 155 000 barrels a day at present.

The majority of South Sudan’s current production comes from the Melut basin in the east of the country, away from where most of the conflict took place.

The two producing oil blocks in the Melut basin deliver 130 000 barrels a day.

The Greater Nile Oil Project (GNOP) fields along the border with Sudan were damaged during the war and are now dependent on cooperation between Sudan, South Sudan and rebel leaders to keep running.

The Toma South field in the GNOP is producing 20 000 barrels a day. The GNOP fields produce sweet crude that is in high demand because it is easier and cheaper to refine, and attempts are being made to get more of the GNOP streams operational.

Sudanese oil minister Azhari Abdalla announced late last year that repairs to the Thar Jath field in South Sudan would begin soon and that it was expected to be operational again in May 2019. This could allow for the production of a further 45 000 barrels a day at full capacity.

New investors

The South Sudan government has repeatedly stated its intention to get the oil sector back to 350 000 barrels a day in the 2020s.

It appears to have grown frustrated with members of the Asian oil industry that are currently invested in the market.

China’s CNPC owns a 41% stake in the Dar Petroleum Operating Company (DPOC) consortium and a 40% stake in the GNOP.

Malaysia’s state-owned Petronas owns a 67.8% stake in Sudd Petroleum Operating Company (SPOC), which operates in Thar Jath; a 40% stake in DPOC and a 30% stake in GNOP.

India’s Oil and Natural Gas Corporation owns a 24,2% stake in SPOC and a 25% stake in GNOP through its overseas arm, ONGC Videsh.

Analysts suggest that these three oil companies have been doing little more than keeping their operations running, despite repeated attempts by the South Sudanese government to get them to invest.

Oil analysts says the Asian stakeholders are holding off to see if peace will remain in the country. A ceasefire, signed in September last year, has led to relatively peaceful times, although sporadic clashes still occur.

Latest deals

The initial agreement between South Africa and South Sudan follows a number of similar agreements signed with Russian companies.

Russian state-controlled oil company Zarubezhneft recently signed an initial agreement to explore four oil blocks. South Sudan also signed an initial agreement with Russian oil producer Gazprom Neft.

Russian oil firm Rosneft is reported to have signed an initial agreement with Nilepet to create a geological map of the country’s mineral deposits.

Nilepet officials have confirmed these deals, but the Russian firms have not.

In 2017, Nilepet signed a deal with Nigerian company Oranto Petroleum for oil block B3, which is part of the B-block that used to belong to French oil company Total.