Sol Plaatje: Witness to the Land Act of 1913

This edited extract from the new biography of one of South Africa’s pioneering journalists details his disbelief at the callousness of a legislative monstrosity, and his unwavering attempts to halt…

Author:

29 August 2018

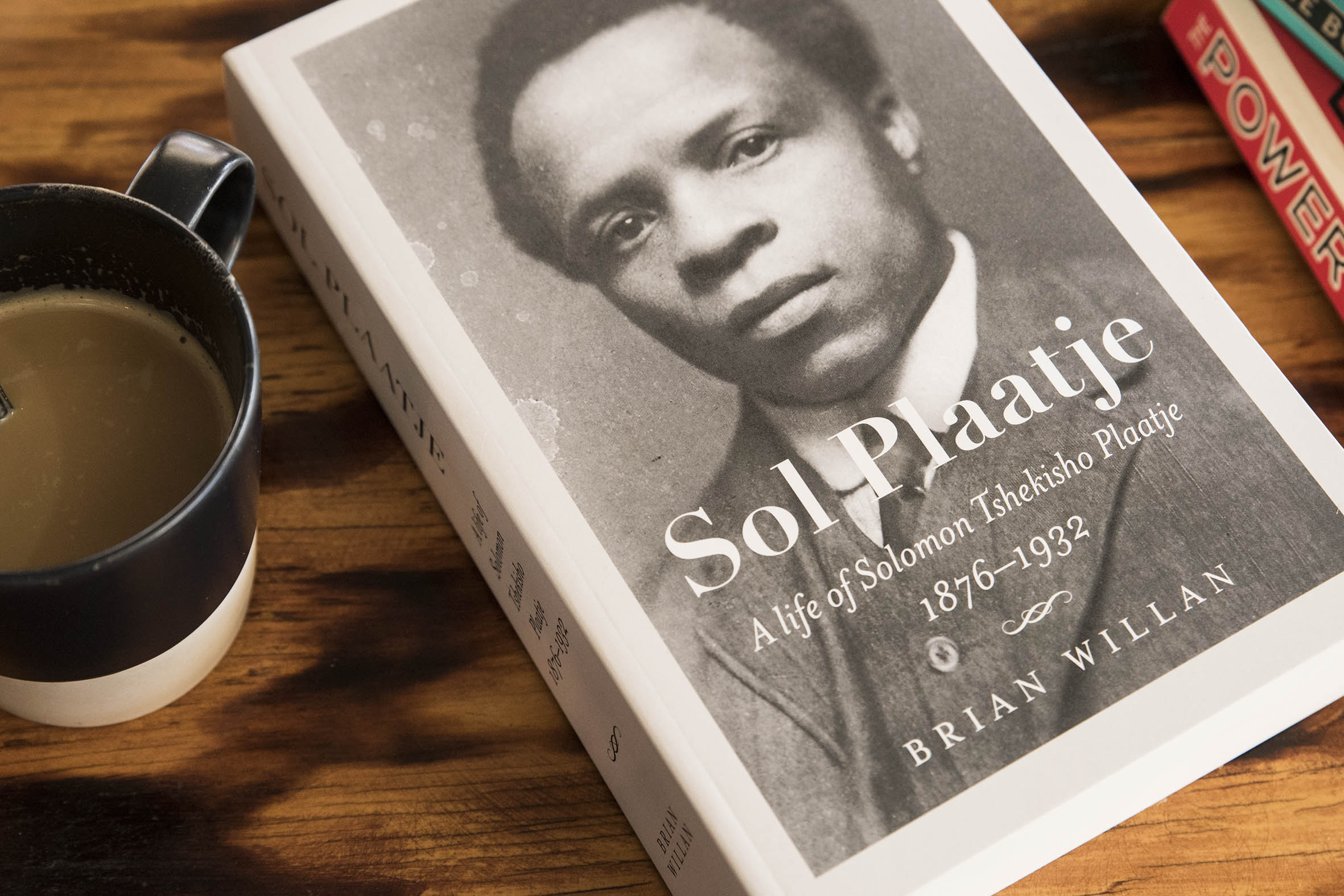

“Sol Plaatje – A life of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje 1876–1932” is a new book by Brian Willan. It is published by Jacana Media. This is an edited extract.

Sol Plaatje’s reaction to the Natives Land Bill, once its provisions became known, was one of shocked disbelief. If somebody had told him at the beginning of the year that the South African Parliament was capable of passing such a law, he said, he would have “considered him a fit subject for the lunatic asylum”.

A “war of extermination”, he now asserted, was what it was. He condemned it as “a legislative monstrosity”, its objective no less than “to steal a whole subcontinent”.

He felt it particularly because it appeared to be aimed specifically at an area he knew so well: the Orange Free State, the province of his birth. Like many of his colleagues, Plaatje had been lulled into something of a false sense of security, politically speaking, by the lack of direction in ‘native affairs’ during the first two years of union. Perhaps, too, his own success in building relationships with government ministers and administrators, even if he recognised the tenuous foundations upon which they were built, had created an illusion of influence in the administration that for a while disguised the highly vulnerable position in which the African people and their leaders now found themselves.

Neither Plaatje nor his colleagues in the leadership of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) were equipped to deal with so momentous and drastic a piece of legislation as the Land Act. They had been brought up to believe in notions of gradual progress and advancement. Setbacks they had certainly experienced in their adult lives – the Treaty of Vereeniging in 1902, the Act of Union more recently – but the ideal persisted. Being able to purchase land, with legally recognised freehold tenure, and to enjoy security as tenants in agreements freely entered into was central to their idea of citizenship, and to their vision of the future. Nothing prepared them for an act such as this. It struck at the heart of their belief in a common society, at their conviction that, ultimately, a shared sense of decency and humanity, between black and white, rulers and ruled, would protect them from measures such as the one now before them. What could they do but respond in the manner to which they were accustomed?

If it became law, they declared in one of their resolutions, “it would constitute the cruellest act of injustice ever perpetrated upon their people.

But as Plaatje, for one, was quick to realise, the Land Act at least provided the opportunity to mobilise support for Congress as never before. Unlike many of the earlier issues with which Congress had been concerned – travelling on railways, or employment in government service – the Land Act threatened the interests and wellbeing of virtually every section of the African population. It thus provided an opportunity to cement the social unity that Pixley ka Isaka Seme had talked of when calling Congress’s inaugural meeting; now it was reinforced by a much stronger sense of common interest and the urgent need to resist the new legislation. For black South Africans, there was no more fundamental or emotional issue than land. A shared sense of grievance bound them together.

At the forefront of opposition

Plaatje was at the forefront of organising African opposition to the Land Act. From the time the bill was first published in February 1913 to its passage in June, and his departure from South Africa as a member of a Congress deputation to England a year later, it was to be his overwhelming personal preoccupation, that of his newspaper, and of the Congress as a whole.

Congress’s response from the beginning was to concern itself not with the principle of the territorial segregation the Land Act claimed to embody, but with the effects it was likely to have. At its first annual conference meeting in Johannesburg at the end of March, in a hall Plaatje described as “packed to suffocation”, delegates discussed the proposed legislation, scarcely believing the enormity of it. If it became law, they declared in one of their resolutions, “it would constitute the cruellest act of injustice ever perpetrated upon their people”. They then appointed a deputation to go to Cape Town to bring their protests to JW Sauer, who had succeeded Barry Hertzog as minister of native affairs.

Plaatje himself was not able, for financial reasons, to travel with his deputation, which went in May, but was present at the special July meeting that was convened to hear its report. The delegates had, so Walter Rubusana related, four interviews with the minister, and further sessions with other members of Parliament. Their protests made no impact, and even their clear willingness to compromise had failed to elicit the slightest response. Herbert Gladstone, the governor general and high commissioner, a keen supporter of Louis Botha’s government, offered no hope either.

Plaatje had written to him requesting that he withhold his assent to the bill until he had heard the “native view”. To this, Plaatje recalled, he “replied that such a course was not within his constitutional functions”. John Dube again approached him after the act had become law, with a request for an interview to inform him of “the nature of the damage that the act was causing among the native population”. He received the same reply.

As the Congress leaders feared, the effects of the Land Act, once it came into operation on 20 June 1913, were immediate and devastating. In July, a meeting of Congress heard from delegates from all four provinces of the way white farmers were taking advantage of the new law to rid themselves of unwanted tenants, or force away others who refused to accept arbitrary demands for their labour.

Plaatje himself, on the journey from Kimberley to Johannesburg, came across some of its worst effects. He had set out from Kimberley in the first week of July in the direction of Bloemhof, on the Transvaal side of the Vaal River, and found there, barely three months after the act had become law, a large number of African families with their stock, who had travelled from the Orange Free State, thinking that the Land Act was in operation only in that province.

Travelling by bicycle, he encountered many of these evicted families on the road, finding it “heartrending to listen to the tales of their cruel experiences derived from the rigour of the Natives Land Act”.

An appeal to the English king

After hearing Plaatje and other delegates recount their experiences of the effects of the act, Congress resolved to appeal directly to the king of England, to the British parliament and, if need be, to the British public to secure the removal of so iniquitous a piece of legislation from the statute book. Since the passage of the Act of Union, the constitutional position was that legislation passed by the South African Parliament had still to be ratified by the imperial authorities, and then to receive the royal assent.

In practice, these constitutional requirements were regarded in official circles as little more than formalities, and only in the most exceptional circumstances was the imperial right of veto thought likely to be invoked. When the legislation in question in any case owed so much to British policies evolved during the reconstruction period, there was never any doubt that the attitude of the imperial government – leaving aside the niceties of the constitutional position – would be one of warm support for Botha’s government. It was upon his shoulders, after all, that hopes of maintaining British influence in southern Africa now rested.

Most of the members of the Congress, even if they did not see things quite in these terms, were well aware that the prospect of persuading the imperial government to veto South African legislation was remote in the extreme. An appeal to the imperial government was, though, the only constitutional option open to them and they decided that they had to take it.

Let our delegates tell the imperial government that we have appealed to the highest authorities in South Africa…and both our appeals, and the church’s representations on our behalf, have been ignored.

They were well aware that other methods were available. The idea of some form of strike action was raised at this meeting by several delegates from the Transvaal, who pointed to the recent example of the white miners. Weeks earlier, they had brought the mines to a halt following an attempt on the part of management to impose new working conditions; a general strike had ensued and only the intervention of imperial troops had ended the dispute.

But those within Congress who wished to resort to such methods were in a small minority and easily outvoted. Plaatje was strongly against the idea. He had an instinctive distaste for any action of this kind, and personally drafted a resolution “dissociating the natives from the strike movement”. Later in the year, he would again take issue with several prominent Transvaal Africans who argued in favour of abandoning the deputation and resorting to strike action instead.

Like most of his colleagues, Plaatje had few illusions about the chances of securing an imperial veto on the Land Act, but believed it was essential to exhaust every constitutional option that existed. “Let our delegates tell the imperial government that we have appealed to the highest authorities in South Africa,” he wrote, “and both our appeals, and the church’s representations on our behalf, have been ignored; and let the imperial government inform our delegates that His Majesty’s kingship over us ceased with the signing of the Act of Union and that whites and blacks in South Africa can do what they please; then only will we have the alternative, and I too will agree that we had better have a general strike, and ‘damn the consequences’. Till then, I will maintain that the consequences of a strike are too serious, and the probable complications too dreadful, to contemplate.”

If the evictions of all the families he had already told the minister about did not amount to suffering…then what did the word mean?

Once it was decided to send a deputation to England, an emergency committee was set up to raise the necessary funds. Plaatje, accompanied by Dube and Sefako Mapogo Makgatho, travelled to Pretoria to convey these decisions in person to the new minister for native affairs, FS Malan.

His response was to try to dissuade them from proceeding with their plan to send a deputation to England, but he had no concessions whatever to offer in return. Nor did the minister’s words inspire any confidence in the prospect of any alleviation in the suffering being caused by the act.

He advised the three of them to wait until the Beaumont Commission reported, “as it was rather too early to judge an act which has been in operation only one month”, and wait until there were “cases of real suffering”. Plaatje asked for a definition of the word “suffering”.

If the evictions of all the families he had already told the minister about did not amount to suffering,” he said, “then what did the word mean?” It was difficult for Plaatje to believe that Malan, a man with a reputation as “a friend of the natives”, and like himself a product of the Cape and its traditions, could have displayed so callous an attitude.

Bitterly disappointed at Malan’s attitude, for he continued to hope against hope that a personal appeal to the human nature of those in power would cause them to think again, Plaatje travelled back home to Kimberley with his colleague from Thaba ’Nchu, JM Nyokong, by way of Vereeniging, Kroonstad and Bloemfontein. In all three places, he addressed meetings about the act, collected further evidence of its effects, and appealed for funds to enable the deputation to travel to England.

This concluding statement, Plaatje reported, “settled the minds of those who had expected from the government any protection against the law, and the disappointment under which the meeting broke up was indescribable.

The women’s protest

At Kroonstad, where he spent a weekend, he also came face to face with the consequences of the women’s protest against the pass laws. For weeks, he had covered their campaign in the columns of Tsala ea Batho – ‘Friend of the People’, as his newspaper was renamed – reporting its progression from polite deputations through to passive resistance, confrontations with the police and mass arrests. He accused the authorities of waging a “war of degradation” against the women. Now 34 of the women who had been arrested and sentenced in Bloemfontein had been moved to the jail in Kroonstad.

When he visited them that weekend, he was appalled to find them in freezing conditions and subjected to forced labour, and he redoubled his efforts to publicise their plight. He would never forget their dogged resistance to injustice, the example they set in defence of their rights. He characterised them as “black suffragettes”, comparing their struggle to the militant campaign for votes for women then at its height in Britain.

At the beginning of the following month, September 1913, he set out on a further tour to investigate the effects of the act in other parts of Orange Free State, and found many more examples of what he had seen during those first few weeks in July: African families wandering from place to place, refusing to accept arbitrary conversion from peasant to labourer but unable to find anywhere else to live. Many of them had congregated around Ladybrand in the hope of being able to cross the border into Basutoland, where the act did not apply, while many of those who lived in the area had been given notice to quit.

The only advice Plaatje could give them was that they should travel to Thaba ’Nchu the following week and listen to an address from Edward Dower, the secretary for native affairs, who was travelling around the country advising on the implementation of the act; and to seek the governor general’s special permission to continue to live on their farms, as was provided for in section 1 of the act.

But Dower had no relief to offer. In his first speech, to the astonishment of the thousand or so people present, he failed even to mention the act. When he finally did so, he gave no indication that the government was prepared to compromise in any way. He explained that the act, through introducing the principle of territorial segregation, was in the best interests of the African population, and advised those present to do one of three things: become servants, move into the “reserves” (he did not specify which he had in mind – there were none in Orange Free State), or sell their stock for cash. He concluded by saying that in Orange Free State, unlike the other provinces, there was no provision for special cases being made through application to the governor general.

I saw little children shivering, and contrasted their condition with the better circumstances of my own children in their Kimberley home; and when mothers told me of the homes they had left behind and the privations they had endured since eviction, I could scarcely suppress a tear.

This concluding statement, Plaatje reported, “settled the minds of those who had expected from the government any protection against the law, and the disappointment under which the meeting broke up was indescribable”.

In November 1913, Plaatje undertook yet another major tour of investigation into the workings of the act, this time to Eastern Cape. While other Congress leaders were collecting evidence and raising funds for the deputation to England in other parts of the country, nobody had yet been doing this in Eastern Cape.

Although there was some uncertainty in legal circles as to whether the act was applicable in the Cape, as its provisions impinged upon the land-holding qualifications for the franchise, itself entrenched in the union constitution, he found that in some places, white farmers were taking advantage of the situation to rearrange their relationships with their African tenants in just the same way as was happening elsewhere.

“I shall never forget,” he wrote, “the scenes I have witnessed in the Hoopstad district during the cold snap of July, of families living on the roads, the numbers of their attenuated flocks emaciated by lack of fodder on the trek, many of them dying while the wandering owners ran risks of prosecution for travelling with unhealthy stock.

I saw little children shivering, and contrasted their condition with the better circumstances of my own children in their Kimberley home; and when mothers told me of the homes they had left behind and the privations they had endured since eviction, I could scarcely suppress a tear.”

What Plaatje saw of the effects of the act remained with him for the rest of his life. It generated a deeper sense of anger and betrayal than anything hitherto, and a feeling of disbelief that fellow human beings could be so callous about the consequences of their actions. Perhaps he also felt a sense of culpability for having misjudged government ministers, many of whom he knew quite well, for having failed to realise that they were capable of supporting such inhuman legislation. His response to the act was deeply emotional and deeply personal.