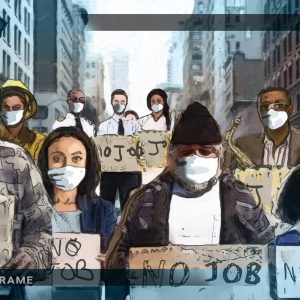

South Africa’s continuing economic pandemic

Grant top-ups and the new social relief of stress grant must be extended beyond October as crucial indicators show that the country’s economic prospects remain grim.

Author:

2 October 2020

By the end of April, the grisly economic outcome of South Africa’s Covid-19 lockdown became clear. The hard lockdown pushed more than 3 million people into poverty after about one in every five workers – closer to one in three if more temporary forms of job loss were counted – lost their jobs.

Figures from 2020’s second Quarterly Labour Force Survey, released this week by Statistics South Africa, and the second wave of the National Income Dynamics Study – Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (Nids-Cram), give an updated prognosis on South Africa’s dire new economic reality.

The two surveys tell similar stories of a job market devastated by the pandemic. Despite considerable easing of lockdown regulations in June, there was not any immediate noticeable recovery of jobs lost to the strictest phase of the lockdown.

The malady

While the number of furloughed workers appears to have fallen, most of the 2.8 million jobs lost by the end of April had not been recovered by the end of June – this is nearly equivalent to the number of jobs created over the past decade. Women remain more likely to have lost their jobs and to have increased childcare responsibilities, while the wage gap between women and men increased from 30% to 50%.

The second wave of Nids-Cram has also given the first indication of the unequal geographic distribution of the lockdown’s effects. South Africa’s already horrendous spatial divides appear to have been amplified. While metros and smaller towns started to recover from the blows to their employment after April, for instance, rural areas continued to lose jobs. In June, unemployment in the countryside stood at 52%, compared with 35% in the metros.

Podcast:

In South Africa’s urban areas, the data show that social grants helped offset poverty and unemployment in townships and shack settlements. But the special Covid-19 social relief of distress grant barely reached shack dwellers. While 27% of township households received the new grant, only 18% of those in shack settlements did, which is a mere two percentage points more than in the suburbs.

This appears to have devastated the material prospects of people living in shacks during lockdown. By June, one in every two homes in shack settlements was still running out of money to buy food at the end of the month, resulting in levels of hunger even worse than those in impoverished rural areas.

The antidote

If the second wave of Nids-Cram data further reveals the grim economic impact of the Covid-19 lockdown, it also contains suggestions of one of the provisional solutions: social grants.

The child support grant was increased by R300 for each of the 13 million children receiving it in May, and by R500 for the 7 million people taking care of them thereafter. Every other grant was topped up by R250. A special Covid-19 social relief of distress grant of R350 was also created.

Despite the failure to recover jobs lost to the hard lockdown, South Africa’s poverty rate decreased by between 3 and 6 percentage points after April, lifting up to 2 million adults out of poverty. The decrease in poverty coincided with the full new package of social grants coming on line, and the evidence suggests that the social relief of distress grant made a significant contribution.

Related article:

While it was dogged by administrative delays in its early phases, the new grant has brought an unprecedented number of new people under the protection of South Africa’s grants system. By August, there were more than 4 million new grant recipients in South Africa. The new grant has also overwhelmingly benefited impoverished households.

In spite of these successes, the exclusion errors remain high, with 6.5 million people who are eligible for the social relief of distress grant not receiving it. The number of people earning the grant also changes on a monthly basis. Only people without any income qualify. Once the South African Social Security Agency establishes that beneficiaries are earning an income again, they no longer receive their grant.

Nevertheless, grant top-ups and the new social relief of distress grant were crucial for keeping food on the table in impoverished homes during a lockdown that decimated informal economies, and they are likely to play as important a role in the long restart of South Africa’s economy. Unless people have enough cash to spend, the businesses holding together towns and communities that subsist on grants are likely to close or stay closed.

Related article:

The new social security package is now coming to an end, with the last grant top-ups scheduled for the beginning of October.

According to Murray Leibbrandt, who directs the Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit and was among the economists analysing the Nids-Cram data, bringing an end to the new grants would be an “absolute calamity”.

The nature of the post-lockdown economy, and the recovery of the labour market, remain unclear. Until we have a better picture, said Leibbrandt, it would be an “absolute necessity for some of this [social grants] package to be extended, at least for six months while we configure what the new social protection and labour market intervention milieu really is”.

Related article:

When asked about the possibility of the special Covid-19 grant and the top-ups of other grants being extended, Minister of the Department of Social Development Lindiwe Zulu said she was “unable at the moment to say it won’t happen”. The primary obstacles, said Zulu, are financial deliberations being made by National Treasury. “When all is said and done, it’s all about discussions that have to happen in terms of balancing the budgets,” she said. Zulu added that the grants package, dealing as it does with poverty, hunger and unemployment, should be a priority for the treasury.

Zulu also said that discussions around implementing a basic income grant – a policy proposal that now has the backing of both the Congress of South African Trade Unions and the South African Federation of Trade Unions, the country’s two biggest labour federations – are continuing, and have “in fact gotten quite far”. The basic income grant is something she said she “will work hard” to realise during her time at the department.

The ball is now in the National Treasury’s court. The evidence released this week will increase mounting pressure on Minister of Finance Tito Mboweni to extend Covid-19-related social assistance when he delivers his medium-term budget policy statement later this month.