South Africa’s golden age of boxing

The sweet science was the most watched sport in the country when South Africa took its first steps towards democracy, creating heroes held in high regard both then and now.

Author:

7 August 2020

Heading into the winter of 1990, South African boxing was entering an age of heroes. As the nation birthed itself anew into the world, the sweet science was eclipsed only by politics as prime producer of champions to help shape our new day.

In spite of the unprecedented political violence engulfing the country, the release of Nelson Mandela and other freedom fighters launched an agenda of positive change. The season called for larger-than-life winners to embody our better possibilities, heroes untainted by the polarised moment to help pause and pull us from the precipice. Four boxers, Thulani Malinga, Dingaan Thobela, Welcome Ncita and Brian Mitchel would rise to become more than gifted athletes.

At the dawn of the 1990s, the Springboks were still largely seen as a symbol of apartheid. Fifa had not yet readmitted our national football team into international competition, so Bafana Bafana’s continental glory was at least half a decade away. Boxing was the prime path to global glory.

The mood in the country was a mix of mass democratic promise and the threat of all-out terror. For instance, consider the so-called seven-day war, a bloody conflict that began on 25 March 1999 in KwaZulu-Natal’s Msunduzi valley. The conflict left 80 people dead and 20 000 violently displaced and homeless.

Between June and October 1990, about 500 people died around Khumalo Street in Thokoza township on Joburg’s East Rand. Around this time, the recently released Madiba was on a global tour reconnecting with, re-energising and thanking the international solidarity movement against apartheid. His message was hopeful and heroic.

An amateur boxer turned president

Boxing’s ability to embody South Africa daring to dream was made compelling in part by Mandela’s affinity with the sport. In his youth, the freedom fighter had been a pastime pugilist. The idea of Mandela being a boxer was nurtured in the popular imagination by the people’s photographer, Bob Gosani, with his now iconic picture of Madiba sparring with champion Jerry Moloi on a Joburg rooftop.

The famous political prisoner reportedly spent his afternoons letting off steam at a boxing gym during the treason trial. The images Gosani captured became part of a campaign to humanise “The Black Pimpernel”. The association was intensified by fighters like Malinga and Thobela declaring their gratitude for a call from Madiba encouraging them ahead of fights.

Related article:

In 1990, Thobela was blazing an inspired path to glory. By April, just 12 weeks after Mandela’s release from prison, The Rose of Soweto had travelled to the United States to challenge the reigning World Boxing Organisation (WBO) lightweight champion, Mauricio Aceves, for his belt. It was the most important fight of Thobela’s career yet. However, Aceves injured his shoulder during training. So the WBO declared the bout a non-title fight.

Thobela was well alive to the symbolic power of a potential victory over a reigning world champion, not only for himself as an ambitious athlete but also for his oppressed countrymen. He delivered a seventh round technical knockout that made the world sit up and take note that there was a South African fighter on the scene who was not to be ignored.

The young Sowetan prospect carried the nation’s hope to a date with destiny later in the year. On 22 September 1990, Thobela returned to face the champion and won a split decision, beating Aceves to assume world champion status. This win catapulted him to becoming a national icon, paving the way for The Rose of Soweto to later become The Rose of South Africa.

The new champion’s ascendence intensified what was to be a legendary rivalry with Mitchell, a white boxer who was five years his senior. Mitchell was already a WBA champion, having won the title in 1986 against Panamanian Alfredo Layne. Thobela would chase him until Mitchell retired in 1995, though they never met in the ring. The two fighters were locked into a singular narrative for good. To this day, fight fans still wonder who would have won.

Mshaye Big John Tate

Unlike earlier white champions such as heavyweight Gerrie Coetzee, Mitchell was better liked by black fight fans. This signalled changing racial attitudes in the land of apartheid. It was in stark contrast to 1979, when Coetzee faced African-American John Tate for the WBA heavyweight title left vacant by Muhammad Ali.

Coetzee’s loss was memorialised in the townships by every black child learning a new Zulu nursery rhyme: “Mshaye Big John Tate (beat him Big John Tate).” Black South Africans saw the black American’s victory as a blow against apartheid’s white racial arrogance. But Mitchell managed to win broader popular purchase across the colour line in a country learning to feel as one. His campaign saw him capture both the WBA and International Boxing Federation (IBF) super featherweight champion belts along with lineal champion honours.

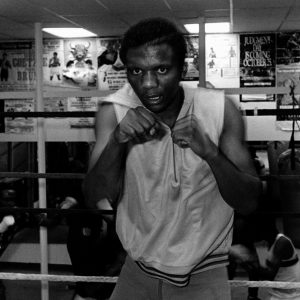

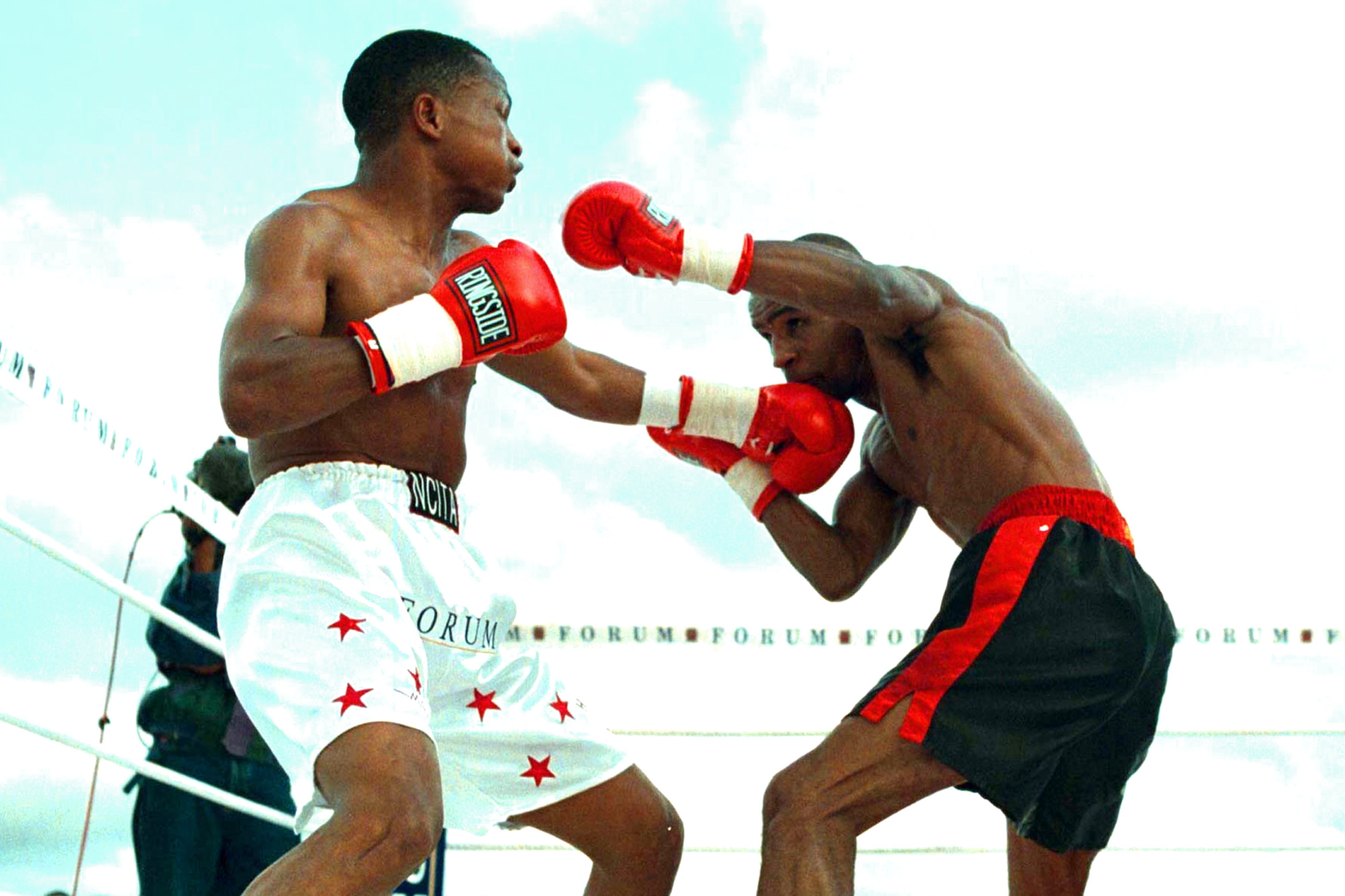

Few fighters have had the quiet mystique of Welcome Ncita. The Hawk, as he was affectionately known, had set the triumphant tone for the year with an inspired win against a rugged French fighter, Fabrice Benichou. Ncita’s sharp jab and crisp footwork saw him capture the IBF super bantamweight title from the Frenchman. In East London, where Ncita was raised amid a rich history and heritage of champion pedigree boxers, he would be particularly lauded. He was the first world champion from a region that was home to legendary pugilists. A hero who made good on his promise.

Related article:

Though not a belt holder as we entered the 1990s, Malinga was a formidable campaigner at middle and light heavyweight during this season, too. The memory of his attempt to capture German champion Graciano Rocchigiani’s IBF super middleweight title in 1989 gained Malinga a special place in the hearts of his countrymen. Malinga would later become the first South African to win a WBC title by beating British brawler Nigel Benn for the super middleweight title in 1996. His spirited bouts with king of the 1990s Roy Jones Jr and the flamboyant Chris Eubank are among boxing’s most memorable fights.

The heroic sportsmanship displayed by these four fabulous fighters ignited a flame whose light still guides many. The heart of every culture lies in the nature of its hero, the essence of its most revered archetypal figure.

The Semitic cultures have historically looked up to “The Man of God”, the prophet, the penitent and ultimately the messiah to find their hero. The anti-colonial Global South looked to the freedom fighter and liberator. For a South Africa that was preparing itself for democracy, a new kind of hero was required. A working-class virtuoso, an ordinary citizen mastering their sheer talent to make beating insurmountable odds look easy.

In the winter that birthed our democratic dispensation, these boxers built us a humanising symbol and standard marred only when Thobela had his halo dislodged by former girlfriend Basetsana Kumalo, who accused the boxer of physically abusing and pointing a gun at her.