State looting calls ANC legitimacy into question

Early admiration in South Africa for President Cyril Ramaphosa’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic has quickly dissolved with representatives of the state stealing emergency funds on a massive scal…

Author:

7 August 2020

When Covid-19 first arrived in South Africa, there was overwhelming support for the state’s strategy in response to the risk of mass infections. It seemed to many that the government was, in striking contrast to the HIV and Aids debacle under former president Thabo Mbeki, taking advice from South Africa’s best scientists and acting decisively to avoid the risk of a devastating health crisis.

That support has now evaporated. It began to wither soon after the lockdown was imposed as it became clear that the police and army were policing impoverished black people in abusive and, not infrequently, murderous ways. Anger escalated as municipalities cynically misused the lockdown to carry out violent and at times illegal evictions.

It then became apparent that the lockdown hadn’t been used to track and trace coronavirus cases or prepare the health system for the coming wave of infections. The lockdown came at a huge social cost, including the loss of three million jobs, and widespread hunger. This social wreckage was, of course, borne primarily by the most vulnerable, whose hold on income, housing and urban land was already precarious. The time won by the initial lockdown was squandered. As a result, it did not prevent infections from snowballing into an avalanche. We now have the fifth-highest number of infections on the planet and a deep economic crisis with which to contend.

Related article:

It didn’t have to be this way. From Senegal to Vietnam and across the Global South, there are many countries that have handled the Covid-19 threat with vastly more effectiveness than South Africa. In some instances, second tiers of government, such as the state of Kerala in India, have also managed the pandemic well. But once again, the ANC has failed. Future historians will add the party’s response to Covid-19 to vast unemployment, atrocious public education, the declining quality of healthcare, the urban crisis, brutal policing and failed land reform on the growing list of its major failures.

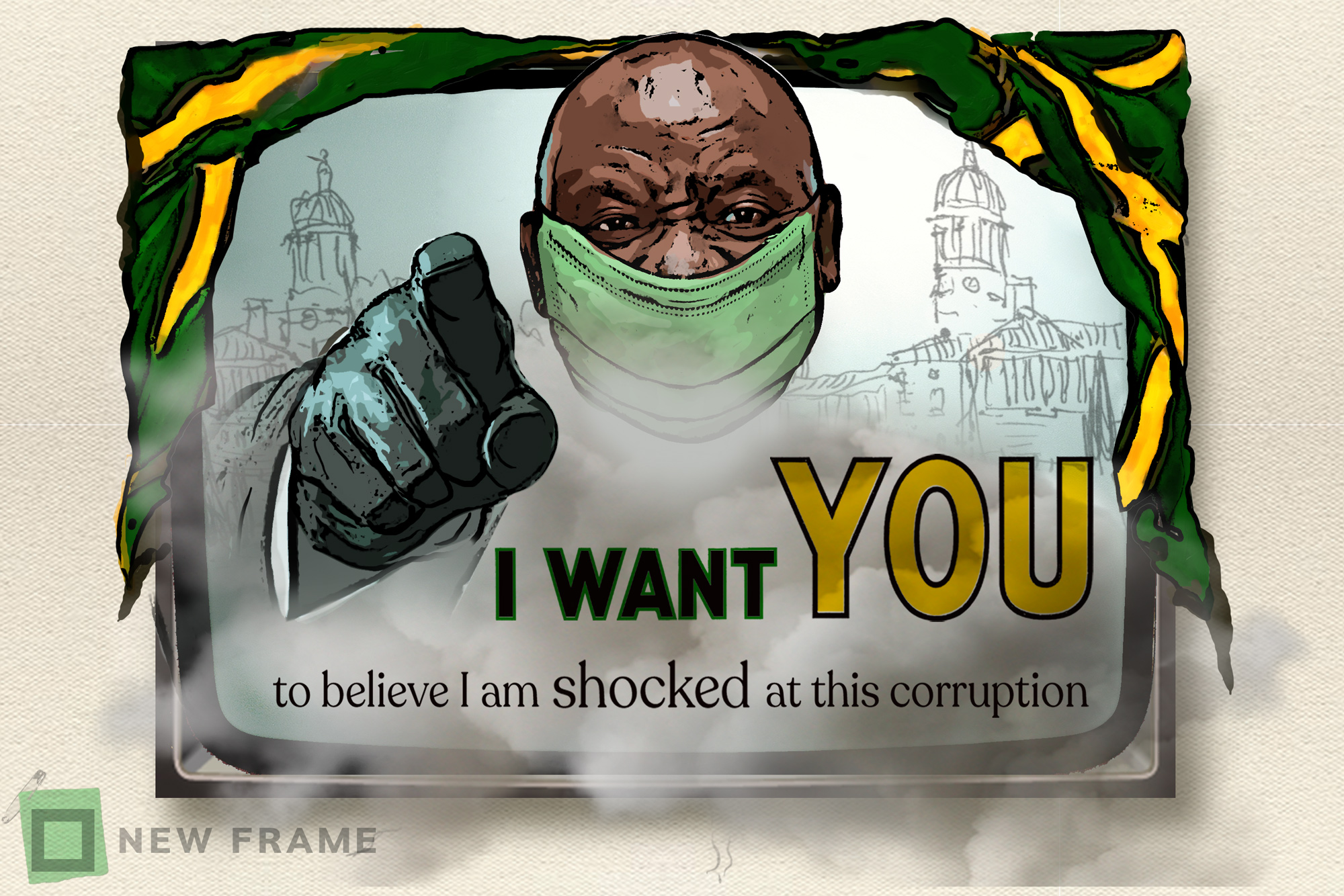

But it was the wholesale looting of emergency funds allocated to address the pandemic that pushed the South African public over the edge. The looting was so brazen, so systemic and so contemptuous of the safety of ordinary South Africans that it produced a gathering wave of revulsion. Driven by the velocity enabled by social media, it has resulted in a sudden but profound legitimation crisis for the ANC.

A public betrayed and angry

Rising public anger over the theft of public funds during the pandemic has been compounded by the misuse of the Hawks to arrest Norma Gigaba following a domestic dispute with her husband, compromised former Cabinet minister Malusi Gigaba. This is not the first time the Hawks have been misused to arrest a woman in conflict with a senior man in the ANC. These actions are deeply sexist and a profound abuse of state power. They illustrate, again, how brazenly the state is used as an instrument for the interests of a predatory political class rather than for advancing a social project.

This public anger has also produced a political crisis within the ANC. President Cyril Ramaphosa would not have been able to come to power without the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) and it seems unlikely that he will be able to hold on to power, or seek a second term, without its support.

Related article:

In a scorching statement, Cosatu served notice to Ramaphosa that if he does not act swiftly and decisively against looting, the federation will withdraw its support for him. Cosatu is insisting, as a minimum demand, on the arrest and prosecution of those involved in looting, something the ANC has long seemed unwilling or unable to achieve.

Cosatu is not making idle threats. When the federation finally withdrew its shameful support for Jacob Zuma, it was clear that his days in office were numbered. If Cosatu can withdraw its support for Zuma, it can do the same to Ramaphosa. The federation and its allies in the South African Communist Party have the power to deal him a serious blow.

Support for Ramaphosa from the Left within the tripartite alliance was always a tactical investment aimed at keeping the kleptocrats at bay. The president is an example of what intellectual Amilcar Cabral called the comprador bourgeoisie, a bourgeoisie that has allied itself to capital, including global capital. Under ordinary circumstances, this would make him a natural enemy of the Left. It is only because of the scale of the kleptocracy that flourished under Zuma and the damage it was doing to society that a tactical alliance was made with Ramaphosa.

For this reason, a long-term arrangement between Ramaphosa and the Left within the alliance was always going to depend on the president delivering on his promise to act – and act decisively – against the kleptocrats. His failure in this regard, which has become manifest at the same time as he has alienated the Left by turning to the International Monetary Fund for a loan, has strained his relationship with his left flank to breaking point.

The looters are vulnerable

The problem has been that powerful forces within the ANC’s national executive committee (NEC) actively and openly support organised corruption. Figures such as ANC Secretary General Ace Magashule are examples of what pan-Africanist Thomas Sankara called the parasitic class, people who turn the state into an instrument for personal accumulation. If Ramaphosa cannot show wider society and his left flank within the ANC that he is capable of effective action against corruption, his presidency will look more than a little vulnerable. But if he alienates the kleptocrats, he will be vulnerable on another front, and particularly within the NEC.

Related article:

But the kleptocratic faction in the ANC does not have the same power that it achieved during the worst of the Zuma years. At the height of state corruption and repression, there was a well-organised propaganda project in support of the “parasitic class” and its kleptocracy, which was farcically misrepresented as “radical economic transformation”. Bell Pottinger, arguably the most notorious public relations firm in the world, played a key role in this project, which included television channel ANN7, The New Age newspaper and the Umkhonto weSizwe Military Veterans Association faction associated with ANC veteran Carl Niehaus, as well as Black First Land First and other individuals and organisations.

Bell Pottinger is no more and the infrastructure used to misrepresent the looting largely collapsed after the Gupta brothers, who were embroiled in the plunder, fled to Dubai. The looters in the ANC now confront popular anger without organised ideological defences. This makes them vulnerable to society. And with public anger at boiling point, massive unemployment and many who had a tenuous grasp on middle-class life facing sudden impoverishment, there is a real possibility of a social explosion.

It seems unlikely that the kleptocratic faction of the ANC will be decisively defeated within the NEC and many regional party structures. For this reason, the Left, in and out of the ruling party, needs to address the growing and potentially explosive rage in society, make common cause with it and attack the kleptocrats from within society. At the same time, it is simultaneously and urgently necessary to oppose the turn to outright neoliberalism led by Tito Mboweni in his role as finance minister, and tacitly backed by Ramaphosa and the rest of the comprador bourgeoisie.