A strange, two-headed rule evolves in Kinshasa

Opposing politicians ostensibly control different aspects of government in the DRC after the recent elections, but could this two-headed regime end up working for the people?

Author:

12 February 2019

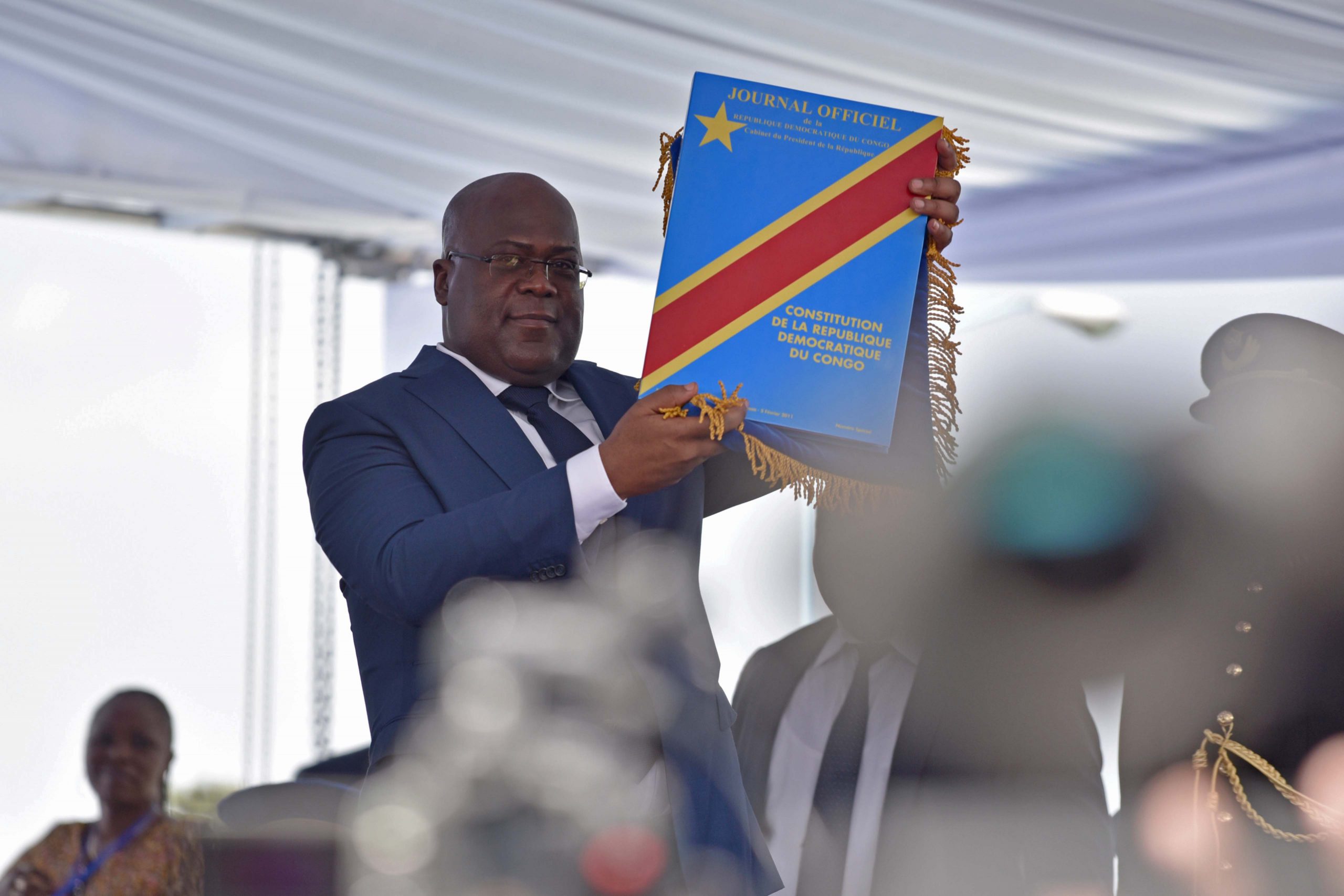

Félix Tshisekedi was sworn in as president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) on 24 January, after a Constitutional Court ruling in central Africa’s biggest country. The ruling followed a much awaited electoral process that came with a catalogue of surprises.

Tshisekedi, 55, was inaugurated in Kinshasa in a non-violent exchange of power uncharacteristic of a country that, since the assassination of Patrice Lumumba in 1961, had previously only changed heads of state through the barrel of the gun or elections widely seen as rigged.

The new president called for unity as the country works towards “its development in peace and security”. He also moved quickly to release some political prisoners, including Christian Lumu, who had been detained without cause or trial since 22 November 2017. He appointed Vital Kamerhe as his chief of staff.

Related article:

Congolese activists, led by the youth, had fought relentlessly for the elections, which, after considerable delays, took place on 30 December. A number of organised groups took a vigilant stand against the kleptocratic regime under former president Joseph Kabila in an attempt to pressure it into holding elections.

Kabila, 47, was in power for almost 18 years and had postponed the elections twice since 2016. The brutal repression meted out to activists calling for transparent elections caused many to flee their homes and to go into exile or hiding. Some were arrested and tortured, while scores of civilians were killed.

About 16 000 people are believed to have fled the town of Yumbi to seek refuge in neighbouring Congo-Brazzaville. At least 890 residents of the town were killed in mid-December in one of the only areas that flared up with post-election violence. The town, which is in the province of Mai-Ndombe, just a few kilometres away from capital city Kinshasa, is an opposition stronghold.

The ‘Kabila system’

The deaths in Yumbi were ascribed to ethnic violence in some quarters. However Kambale Musavuli, spokesperson for Washington-based advocacy group Friends of the Congo, said this depicts the Yumbi violence out of context.

“The situation in Yumbi is very reminiscent of what has unfolded in Kasai, a region where over 100 mass graves were found in 2017. UN experts were killed during an investigation and the people from the area stood up to the Kabila regime by demanding an election and for him to step down,” said Musavuli, who insists that the deaths are related to the elections.

Related article:

He said the election “results don’t necessarily reflect what the masses expect”, adding that there is no real victory as Kabila’s system still remains in place after Tshisekedi won out of 21 presidential candidates.

“Félix didn’t win the presidential elections. He was integrated into the Kabila system,” said Musavuli.

Kabila congratulated Tshisekedi, handing power over to him “without regret or remorse”. On state TV channel RTNC, Kabila called for a “coalition against the predatory forces that have come together and will always try to join forces to monopolise our natural resources”.

There have been murmurs that Tshisekedi’s victory came about as a result of a clandestine power-sharing deal with Kabila, which will see Kabila continuing to pull the strings in the background. Tshisekedi has rejected claims that he secured a back-door deal with the outgoing president.

Political inexperience

Tshisekedi’s father, Étienne Tshisekedi, was the leader of the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDSP) party and one of Kabila’s biggest political rivals. He died in February 2017 aged 84 and his death propelled his son into a career in politics. Tshisekedi’s educational background has been an issue of dispute with claims that he did not complete a marketing diploma from Brussels, Belgium.

Étienne Tshisekedi claimed that the 2011 elections were rigged and called for a legislature boycott, meaning that although Félix was elected as a member of Parliament, he did not serve.

The younger Tshisekedi’s limited political experience has raised eyebrows about his ability to lead as party and coalition leader.

Related article:

Musavuli believes Kabila met with Tshisekedi to strike a deal when he realised his intended successor, Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary, might not win. He said Kabila has installed loyalists throughout the federal bureaucracy and his coalition won a majority in the legislative elections.

“Kabila has most of what he wants, control of Parliament and control of the provinces. With him having control of these arms of the state, he can control [Tshisekedi] and continue his agenda.”

In the DRC, senators are elected by the provincial governments. Most of the members of the provincial governments are from the Kabila regime. Once a president has left office, he becomes a senator for life. This gives Kabila access to power as his majority can ensure that he is elected as the head of the Senate, making him president should the president be incapacitated in any way.

Crises before elections

Following a meeting in Geneva, Switzerland, the Congolese opposition signed an agreement on 11 November 2018 that announced Engagement for Citizenship and Development party leader Martin Fayulu as its joint candidate for the presidential election. In just 24 hours, the deal fell apart as Tshisekedi and Kamerhe withdrew their signatures.

The introduction of new electronic voting machines was met with suspicion by many Congolese, who had never used them before. The South Korean government distanced itself from South Korean firm Miru Systems, which was providing the electronic voting machines, saying that the use of voting machines in the DRC had failed to gain support from international watchdogs.

In an unprecedented move, residents of Beni, Butembo and Yumbi were told they would not be able to vote until March – long after the inauguration – owing to Ebola concerns. This robbed more than a million citizens of the chance to participate in choosing their next leader. MSF (Doctors Without Borders) said the virus that has plagued the country was under control and gave the medical go-ahead for elections to be held in these areas.

But more than 10 000 residents from Beni, an opposition stronghold, came out and voted anyway. In some places, voters waited for up to five hours. Some were turned away and others sat in the rain waiting to vote in an act that indicated that the fatigued but irrepressible Congolese citizens were taking control of the affairs of the country instead of leaving it to the self-serving government.

‘Electoral coup’

Independent observers from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and African Union (AU) asserted that the elections went well. Other observers questioned the integrity of the voting process as the elections were marred by an avalanche of irregularities and diminishing public trust in the electoral body, the Independent National Electoral Commission (Ceni).

The Catholic Church’s National Episcopal Conference of the Congo (Cenco), which had also observed the 2011 elections, deployed 40 000 observers, implying at a press conference that it knew the true winner and that election officials must come out with the real winner to the people.

The initial results were met with a chorus of indignation, particularly from Fayulu, who angrily characterised the official result as an “electoral coup” and contended that he had won 61% of the votes.

After being down for almost three weeks, internet access was finally restored. Internet blackouts, which have happened previously, are an effective way of suppressing the spread of information – particularly around election time.

Working in tandem

The DRC is home to a plethora of moneyspinning minerals and coveted raw materials, making it a sought after country for corporations looking to go into cahoots with a power-hungry government.

But while corporations and the ruling elite are making vast amounts of money, there is a dearth of money and food in many parts of the war-torn country, highlighting the contemptuous attitude adopted by leaders towards ordinary citizens. Violence and impoverishment are endemic.

Musavali said it is a travesty when political and corporate elites work in tandem to advance their own interests against those of the people as a whole, adding that this is also the case in South Africa.

Related article:

“People in the financial sector in South Africa are worried that change in the Kabila regime will reconfigure their access to Congo’s resources and they are not willing to see the change,” he said plainly.

Although the AU appeared to come closer to the will of the Congolese people by calling for a suspension of election results in January, SADC issued a congratulatory statement to the country for their smooth elections. South Africa’s Department of International Relations and Cooperation hailed the elections as an opportunity for a new dawn and asked for citizens to respect the DRC’s electoral process.

Before the elections, the AU asked for European Union (EU) sanctions to be dropped against Shadary, who was sanctioned along with other pro-Kabila associates for their role in human rights abuses. Neither Kabila nor his family have any sanctions against them.

These organisations have proven to be toothless when faced with making ethical decisions, opting to allow regimes to handle issues without interference rather than adhering to and adopting policies in founding documents.

International reservations

President Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya was one of the only heads of state seen at the swearing-in ceremony, cementing the view that a number of states may have reservations over the alleged election fraud that brought Tshisekedi to power.

The AU missed an opportunity to be a pivotal actor in this crisis by remaining a bystander, projecting an image of incompetence and effectively abandoning the rule of law with its derogation from the Windhoek treaty of 1992. This is a SADC founding agreement promoting human rights and respect for the rule of law that encourages sanctions against those who persistently fail to meet these obligations.

As Kabila steps down, this may or may not be a victory for the Congolese people. On the one hand, the office of the presidency is handed over to the opposition, on the other the legislature and provincial governments remain predominantly pro-Kabila.

More broadly, what the DRC elections have highlighted is a misconceived notion of African solidarity, which results in an unwillingness to antagonise other African states while tyrannies continue to operate with impunity. Perhaps in the DRC, after the regimes of the two Kabilas, African states and the AU will feel compelled to act on the unbridled violence dished out by those in power.

For the citizens of the DRC, long brutalised by a toxic combination of state and corporate oppression, it remains to be seen if there is some good in the strange, two-headed rule evolving in Kinshasa.

This article has been updated to reflect contested views about Tshisekedi’s educational history.