Text Messages | An 18th-century lesson in power

Women and the working class would do well to draw on Pierre-Augustin Beaumarchais’ work to subvert social hierarchies, as did Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Lorenzo da Ponte.

Author:

2 July 2020

The most revolutionary text of the late 18th century was not a piece of political nonfiction. Instead, it was the script for Le Mariage de Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro), the wicked comedy of class and sex by Pierre-Augustin Beaumarchais. That it had a reputation for notoriety among the ruling and upper echelons of Europe of the day was down to its relentless fun at the expense of the male nobility.

Figaro, the servant class and women run rings around their “better”, the selfish, grasping and myopic aristocrat who is the play’s antagonist. On a continent of emperors and kings, dukes and counts and marquesses, the play was like a match thrown into a keg of gunpowder. It was not merely how servants outwitted, outmanoeuvred and commented on their masters and mistresses. It was that these actions were an implicit appeal for the levelling of the social hierarchy.

Beaumarchais had cannily set the action not in his native France but in neighbouring Spain, although the shift in location did nothing to disguise the “cheek” of the play’s message. Among its memorable shafts of satire is when the Count, remarking to Figaro that servants took more time to dress than their masters, is met by the smart response that servants do not have valets to dress them.

Related article:

To a 21st-century ear this might seem relatively inoffensive. In the aristocratic tenor of the times, it was insolence unheard of. That a servant should be verbally jousting with his master was not something to be put on stage: it was positively unfit for public consumption.

But as radical – and perhaps even more so – was Beaumarchais’ second theme, the standing of women. Treated in real life and in much art of the time as baubles to play with and then be abandoned when the desires and appetites of their male pursuers were sated, women were at least as desperately in need of a social revolution as the working class. That Beaumarchais constructed a plot and story in which the Count is foiled and defeated by his own wife and her chambermaid Susanna was a shocking outcome to the “genteel” upper classes.

Ceaseless fooling

The Count, harking back to the medieval droit de seigneur – the right of the lord of the manor to have sexual intercourse with brides-to-be before their marriages – is in pursuit of Susanna, Figaro’s fiancée. This repulsive would-be rapist is thoroughly beaten by the female solidarity of the countess and Susanna and by his valet, the wily, witty and subversive Figaro.

When the play was performed before Louis XVI of France he declared it “detestable and unplayable”. It proved anything but. Louis found not the Count’s behaviour objectionable, but Figaro’s, ceaselessly fooling his master. Others loved that inversion of power, and such was the popularity of the egalitarian and revolutionary comedy that Emperor Joseph II banned its performance in Vienna, regarded as more enlightened than Paris.

It was to this script that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and his librettist Lorenzo da Ponte applied themselves, turning it into the one of the greatest of all operas, Le Nozze di Figaro. Joseph II allowed it to go ahead because Da Ponte assured him he had cut the naughty bits lampooning the nobility.

Nothing could be further from the reality of Figaro. In his very first aria, the quicksilver-tongued Figaro throws out a challenge to the Count: “Se vuoll ballare, signor Contino (If you would dance, my noble lord).”

Another world

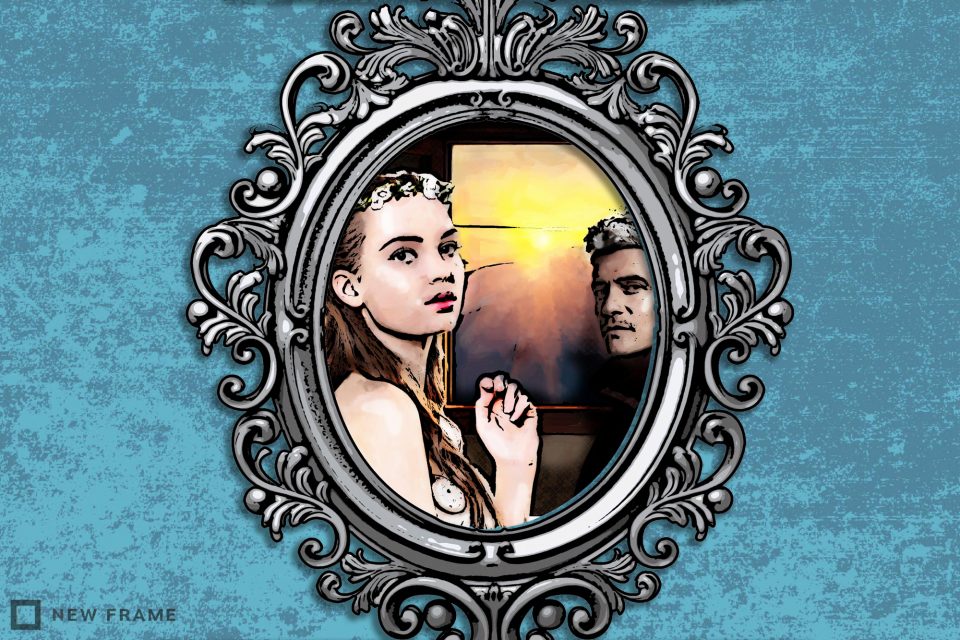

Indeed, right from the beginning, there is a plea for a different, more equal and better world. In a small room we find Figaro and Susanna. She is looking at herself in a mirror as she tries on a floral headdress. He is on his knees, a measuring rule in hand.

“Five, 10, 20, 30, 36, 43,” he counts, measuring the room. “I’m seeing if that bed the Count is giving us will look well here,” he says.

“For my part you can keep it,” she says, adding in answer to his asking why, “I have my reasons here,” tapping her forehead.

It is pointed, succinct, deeply human as only Mozart can be. Beyond this small room, into which the malevolent Count wants to intrude his presence, is another world, and Susanna knows it.

Across the border from Austria, in Prague, the opera was met with sheer joy. When Mozart visited there in early 1787, he found people singing and whistling the opera’s songs and melodies and talking about its twin themes: equality for humankind and for women.