Text Messages | Artefacts of the mind

Donald Trump has threatened to ‘obliterate’ Iran’s cultural treasures despite the ICC deeming this a war crime, but he fails to realise that works such as those of Sufi poet Jelaluddin Rumi will li…

Author:

9 January 2020

When the Vandals sacked Rome in 455, their name was appropriated for all time as a byword for wanton destruction and looting. That is a very unfortunate legacy for people who were originally farmers and pastoralists from Scandinavia.

Over the course of the centuries preceding their attack on Rome, they migrated ever southwards, first into what is now Germany, then crossing the Rhine into Gaul. From there they moved into modern-day Spain and then into north Africa, capturing Carthage in 439.

But while they “vandalised” Rome, it was not the excess of pillaging and burning and killing of popular imagination. Instead, before entering the city they had talks with Pope Leo I, who persuaded them not to wreak havoc. The Vandals made off with material wealth but did not prey on buildings; when they had gathered their booty, they turned round and left for home.

Related article:

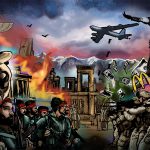

Nonetheless, entirely negative connotations have stuck to “vandal” and associated words and concepts. A recent usage linked events in 455 with possible happenings in 2020. When United States President Donald Trump threatened to destroy Iranian cultural sites should Iran retaliate for the assassination of Lieutenant General Qassem Soleimani, his warning was widely described as “cultural vandalism”.

More pointed and to the point was Steve Rose in The Guardian, who wrote that if Trump’s threat was carried out, it “would put him into an axis of architectural evil alongside the Taliban and Isis, both of which have wreaked similar forms of destruction this century”.

Irreplaceable treasures

On 27 June 2019, this column noted that: “In the fraught atmosphere of Iran-US relations, with tensions rising in the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz, there is the probability of the world’s first empire (Persia, today’s Iran) being attacked by the world’s last empire (the US). Perhaps ‘attacked’ is too neutral a word: US President Donald Trump has threatened Iran with ‘obliteration’. The scenario is awful: an ancient culture and civilisation being attacked by a degraded society driven by patriarchy, machismo, money, racism and Twitter storms.”

Related article:

The danger to Iran’s irreplaceable cultural treasures is extremely high right now. Commentators have decried the Trumpian ultimatum. Academics have resorted to the open-letter protest, pointing out that the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague regards destruction of cultural heritage as a war crime. Given that the ICC has been able to do little in pursuit of those accused of war crimes involving genocide, the open-letter convention here seems puny, an act of optimism touched more by bathos than pathos.

But even if the worst should happen and some or even many sites be destroyed by sheer barbarity, the ideas behind them will remain. Despots never seem to realise that destroying the property of one’s enemies, or killing them, cannot expunge their ideals, messages and ideas. As the Dalai Lama reflected on the increasing disappearance of Tibetan culture, the idea of Tibet will live on, even if the place and its people do not.

Economy of words

That is cold comfort for Iran and its people, waiting no doubt for a rain of US retaliatory bombs and missiles should Iran take revenge for Soleimani’s killing. But among the many artefacts of the Iranian mind that will survive are the works of Jelaluddin Rumi, the 13th-century Sufi poet.

Born on 30 September 1207 close to the city of Balkh at the eastern frontier of the Persian Empire, Rumi came from a long and respected line of Islamic theologians, jurists and mystics. He died on 17 December 1273 in Konya, in present-day Turkey, having written or dictated tens of thousands of lines of poetry and created some the greatest works in the literature of the world.

Rumi is often over-simplistically characterised as the great poet of love. That he is, but of much else besides. His economy and profundity are in every piece of his writing, such as this:

Come, come, whoever you are,

wanderer, fire worshipper, lover of leaving.

This is not a caravan of despair.

It does not matter that you have broken your vow

a thousand times, still come,

and yet again come.

(From Rumi: The Big Red Book, translated by Coleman Barks, 2010)