Text Messages | The colonial massacre of Congo

The West began slaughtering the Congolese in the late 19th century, and orchestrated the assassination of its first democratically elected prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, in 1961.

Author:

24 January 2019

The massacre of Congolese by Belgians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries is among the worst genocides in history. According to the definitive work on the subject, Adam Hochschild’s King Léopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa (1998), the population exceeded 20 million in 1891 but fell to 8.5 million by 1911.

Almost 12 million people vanished, disappeared, slaughtered. The sheer enormity of that figure makes it difficult to come to terms with because the individual humanity, and the millions of human lives cut short, disappear in the morass of the annihilation.

Yet, for almost a century after the genocide, one would have been hard pressed to find an honest account laying blame at the door of the killers. Take this entry from The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th edition, 1986:

“The chief industry, wild rubber production, became particularly lucrative after 1891, but in 1904 exposure of mistreatment of natives in the rubber industry marked the onset of the decline of Léopold’s personal rule in the region. Great Britain, with US aid, pressured Belgium to annex the Congo state to redress the ‘rubber atrocities’; the area became part of Belgium in November 1908.”

Related article:

We are here in the region of euphemism central: “mistreatment of natives” and “the ‘rubber atrocities’” hardly gives a hint of the elimination of millions of people, which Léopold and his flunkeys viewed more probably as an extermination, their victims eliciting no more sympathy than would a pack of plague-ridden rats.

And then there are the mutilations that were a byproduct of the rubber industry. The Dunlop rubber company loved Léopold II’s access to wild rubber and the guaranteed enormous quantities that flowed to it. Company and monarch were mutually enriched at the cost of thousands of Congolese having their hands chopped off, those workers who failed to harvest enough rubber.

Léopold II lived from 1835 to 1909. About midway through his life, he discerned the chance for grandeur (in his understanding of that term) and formed the Association Internationale du Congo in 1876 to explore an area 80 times the size of Belgium. Léopold appointed Sir Henry Morton Stanley as his main agent.

Western historical lore — and books of “famous” quotations — remember Stanley as an intrepid adventurer and explorer and as the man who, whether apocryphally or not, uttered the address “Doctor Livingstone I presume?”. Stanley’s efforts and the successful repulsing of an Anglo-Portuguese attempt in 1884 to seize the Congo Basin allowed Léopold to declare the État Indépendant du Congo — the Congo Free State — which was recognised by the United States and major European powers at the infamous Berlin Conference of 1885. The stage was set for the looting and killing.

Related article:

It is significant that Léopold died relatively soon after the excesses of his personal sovereignty of the misleadingly named Congo Free State were exposed. That was owing in large part to Sir Roger Casement, who was commissioned by the British government in 1903 to investigate human rights in the Congo Free State. Casement was British consul in Boma at the time.

Casement journeyed up and down the upper Congo Basin, speaking to workers, and supervisors and mercenaries in Belgian employ. His comprehensive and minutely detailed report spoke of “the enslavement, mutilation, and torture of natives on the rubber plantations”. No politeness or understatement in what was subsequently named the Casement Report of 1904, but instead refreshingly straight talk based on extensive eyewitness experience.

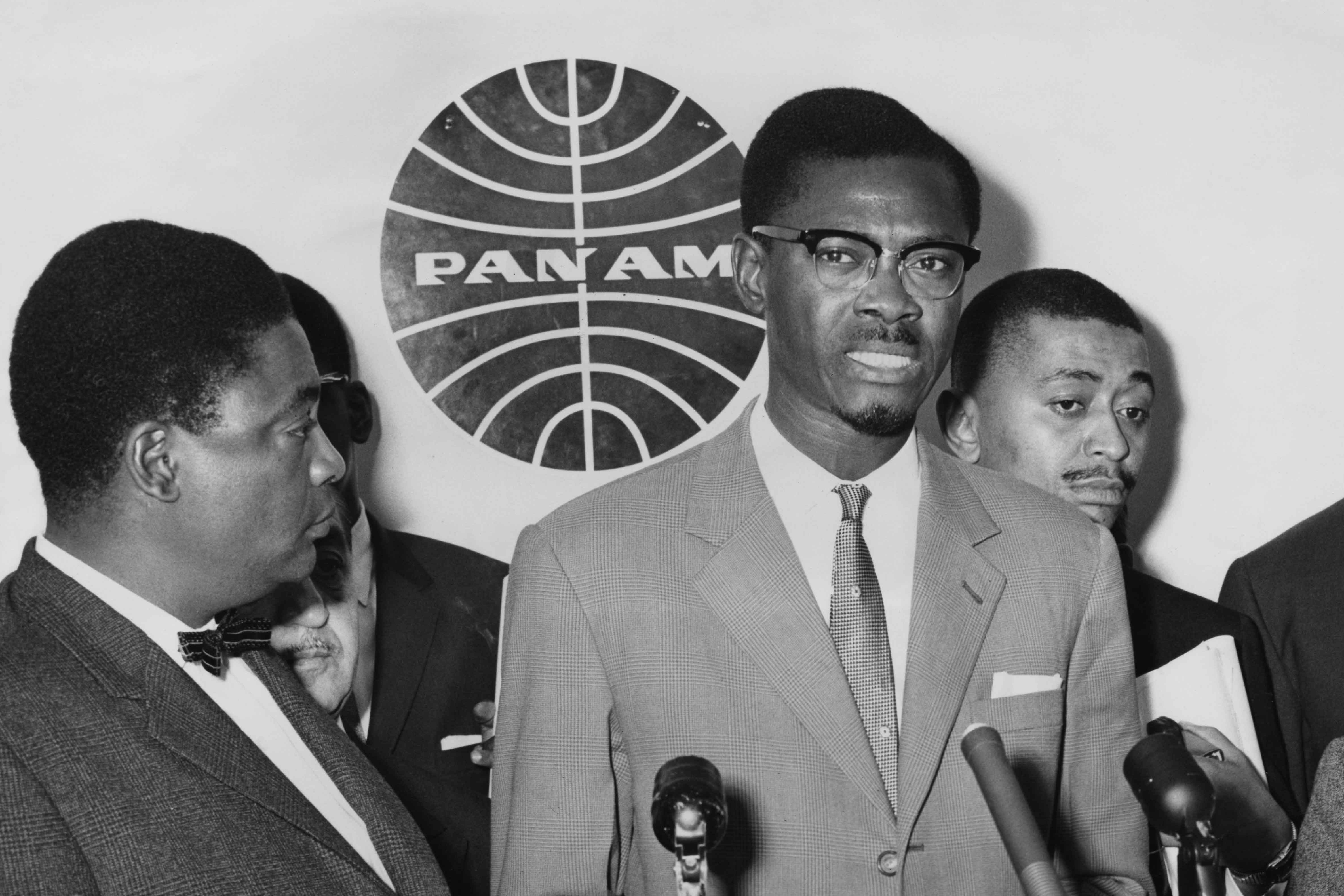

It was into the aftermath of this colonial mess that Patrice Lumumba ventured in the late 1950s.

Grudgingly acknowledged as the Congolese leader-to-be by the West, nonetheless Lumumba almost simultaneously became a man more plotted against than plotting. Here is how Leo Zelig, in Patrice Lumumba: Voices of Liberation (2013), describes the monstrous forces ranged against Lumumba:

“Documents released in the United States in August 2011 reveal that President Eisenhower directly ordered the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, who was the first democratically elected prime minister of Congo. Minutes of an August 1960 National Security Council meeting confirm that Eisenhower told CIA chief Allen Dulles to ‘eliminate’ Lumumba.”

The US and its agents did not need to dirty their hands because the Belgians, the defeated colonial masters in Congo, did the Americans’ work instead. On 17 January 1961, Lumumba was executed by a firing squad marshalled by a Belgian officer, at a killing site prepared by a Belgian. Lumumba’s corpse and those of his fellows — Joseph Okito and Maurice Mpolo, also murdered by firing squad — were hacked into smaller pieces that were thrown into canisters of acid, a piece of work carried out by a Belgian police officer, Gerard Soete.

Matthias Kamishanga, faithful to Lumumba throughout, recalled his comrade’s last speech, to the soldiers who intercepted him at the Sankuru River on 30 November 1960 when he was trying to reach the safe haven of Stanleyville. It is quoted in Zelig’s book and speaks eloquently of the stature and humanity of Lumumba.

“If you kill me, I will not die. If you throw me into the river, the fish will eat my flesh. The Congolese will eat the fish, and then I will be in the bellies of the people and I will never be far from my people. I will be in the belly of each Congolese.”

Perhaps it was because of this that the Belgians who murdered Lumumba chose so barbarically to erase all traces of his body.