Text Messages | Covid-19 and the rise of AI

EM Forster’s 1909 story about a world controlled by the Machine is eerily prescient as governments turn to artificial intelligence to monitor, track and control citizens during the coronavirus pand…

Author:

28 May 2020

At the beginning of the 1950s, two thinkers publicly addressed the practical and philosophical problems posed by artificial intelligence, or AI. One was the mathematician Alan Turing, the other the biochemistry professor and science fiction writer Isaac Asimov.

In a 1951 lecture, Turing said that humankind should expect the machines to take control once their capabilities exceeded ours. To show what he meant he pointed to a striking example, which he dubbed “the gorilla problem”. Gorillas had been overtaken by their close relative, humans, and there was nothing that the primates could do to reverse Anthropocene superiority.

In a series of short stories and novels, Asimov elaborated the Three Laws of Robotics. He had first introduced those in the short story Runaround (1942), but it was its republication in a 1950 collection that brought them to prominence. The laws are:

First Law: A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm

Second Law: A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

Third Law: A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

The Asimov laws posit ethical and moral dilemmas of which their creator was only too conscious for the next 40-odd years until his death in 1992. In a 1987 essay, The Law of Humanics, Asimov noted:

“We might even imagine that as a robot becomes more intelligent and self-aware, its brain might become sensitive enough to undergo harm if it were forced to do something needlessly embarrassing or undignified … I honestly think that if we are to have power over intelligent robots, we must feel a corresponding responsibility for them, as the human character in my story The Bicentennial Man said.”

Simple solution

The situation in 2020 would seem to point more to a Turingesque, gorilla-like outcome than to an Asimovian accommodation between man and machine. If that sounds like a piece of alarmist science fiction-speak, it is well to note the cautions given by Stuart Russell, the neurologist and computer scientist. Founder and head of the University of California Berkeley’s Center for Human-Compatible Artificial Intelligence, Russell says that truly intelligent AI would have the capacity to solve problems that humans can describe but cannot resolve.

One example he has used when talking to lay audiences is how the machines could sort out the excess of planetary carbon dioxide. A simple and guaranteed way would be to remove the source of most of the excess: humans and with them the human activity responsible for killing levels of anthropogenic pollution.

Related article:

It is these unintended side-effects of intelligent AI that need to be restrained, Russell says in his recent book, Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control (2019). The way to do that is threefold, he says. One, the machine must enable the satisfaction of human preferences. Two, the machine knows that it does not know what those preferences are. Three, the machine connects humans and machines to seek out those preferences.

What results from this is a mathematical problem with two entities, human and machine. Solving the machine part will ensure “deferential behaviour” from AI that is “minimally invasive” and does not presume to know human preferences. For example, one way to tackle carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would be to make sulphuric acid of the world’s oceans. But AI in sync with humans would first ask if that was a human preference, not just deliver a guaranteed solution.

It is cheering that a world expert in the AI field thinks humankind can avoid the gorilla problem. Notably, Russell does not delve into the almost imponderable area of machines developing sensibilities and consciousness, as Asimov did. But whatever Russell’s optimism, the way that AI has been harnessed by governments around the world to help in the fight against Covid-19 must give one pause for thought.

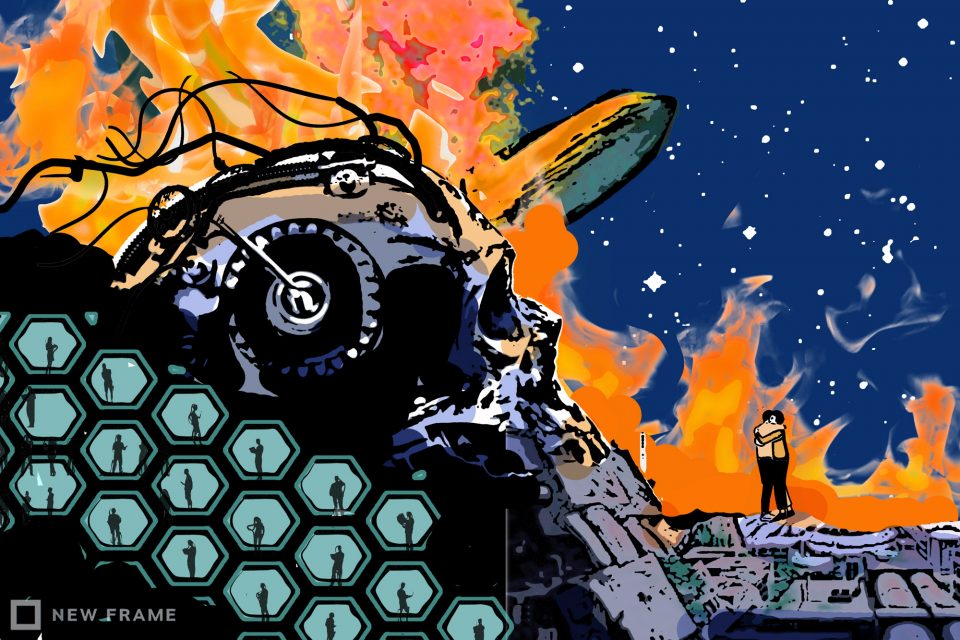

Facial recognition, tracing by phone apps and all sorts of other surveillance possibilities are really only the leading edge of the massive AI truncheon that governments can bring to bear on their citizens. An ultimate fate arising out of increased monitoring and control of humanity by AI was never better portrayed than in The Machine Stops, the 1909 science fiction short story by EM Forster. Yes, the same Forster who wrote A Passage to India and other classics of English literature.

Bleak new world

The world of The Machine Stops is bleak for humans, though few of them realise that is so. People live beneath the earth in small, bee cell-like rooms where their physical and leisure needs are taken care of. They can summon food, music, their beds and their baths at the touch of a button. There is no reason to leave their vast subterranean dormitories and besides that daylight and even the beams of the moon are painful to the eye. Physical activity and exercise are superfluous. Travel is possible in airships from one part of the globe to the other, from hemisphere to hemisphere, but hardly anyone chooses to journey anywhere. Instead, there is the chant that “The Machine is the friend of ideas and the enemy of superstition: the Machine is omnipotent, eternal; blessed is the Machine.”

Ideas are the important thing. People give lectures via what can be described as Forster foreshadowing video conferences. His world also includes an internet equivalent and isolation – indeed, voluntary self-isolation, a chilling analogue in this coronavirus time.

A few rebellious escapees see the surface of the Earth, its air and skies and greenery. One such is Kuno, who lives in the North; his mother Vashti, living in the South, is his antagonist. When Kuno escapes the underground confines of the settlements, he breaks out into the old world. For that reckless and illegal deed, his future becomes a likely sentence of Homelessness: banishment from the warren of living cells in which people exist under the seemingly benign and nurturing hand of the Machine.

Related article:

What happens to Kuno and this extremely inhumane world – physical touching is frowned on as an absolute no-no – speaks not only to the Turing problem of the gorilla overtaken but also to our new world that might emerge to accommodate cohabitation with Covid-19. That could be a place in which the Machine does not stop, because it is acting at the behest of evil governments run by craven men.

To read Forster is, perhaps, to glimpse the future:

“Cannot you see, cannot all you lecturers see, that it is we that are dying, and that down here the only thing that really lives is the Machine? We created the Machine, to do our will, but we cannot make it do our will now. It has robbed us of the sense of space and of the sense of touch, it has blurred every human relation and narrowed down love to a carnal act, it has paralysed our bodies and our wills, and now it compels us to worship it. The Machine develops – but not on our lines. The Machine proceeds – but not to our goal. We only exist as the blood corpuscles that course through its arteries, and if it could work without us, it would let us die.”