Text Messages | Hailing all jesters

A true jester, a seeker and teller of truth through wit and satire, upholds the ‘dignity of the downtrodden’. Unlike certain buffoons of the modern sort who play at politics.

Author:

20 June 2019

They are very much words of the moment: buffoon and buffoonery. In the liberal media in the United States and the United Kingdom, they are often attached to or hover around the proper names Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Unflattering as these associations are, they at best paint only half the picture, which is a tragedy for both truth and language.

Consider two contemporary senses of buffoon: a ridiculous but amusing person and a person who does silly things, usually to make other people laugh. In both instances, the first part of the definition applies to Trump but not the second: he is ridiculous and far more than “silly”, but he is neither amusing nor intending to provoke laughter. On other grounds, buffoon and Trump are more happily joined, as in a person given to coarse or undignified joking.

Transatlantic nuances in language also pit American English against English. Buffoons are synonymous with clownish public figures in the US whereas in the UK there can be a degree of leeway and even affection afforded the buffoon. Johnson is a prime example of someone whose utterances and deeds are offensive and unfunny to many but popular and amusing for others. Where one is on the spectrum of disapproval and approval depends on one’s politics and sense of fairness, equality and social justice.

The origins of buffoon are simple and straightforward, unlike the contorted connotations that the word now carries. Buffone is jester in Italian, from buffo, clown in Latin, from the verb buffare, to puff. It’s about pointed hot-airing, huffing and puffing and wagging and mocking and jesting.

And in bygone days jesters were licensed to give the monarchs they served a hard time, reminding them of their frailties and flaws, mistakes and misjudgements, idiotic and ludicrous actions. While the jesters puffed out their jibes, they deflated the rulers’ false airs and graces, and grounded them again by sending them up.

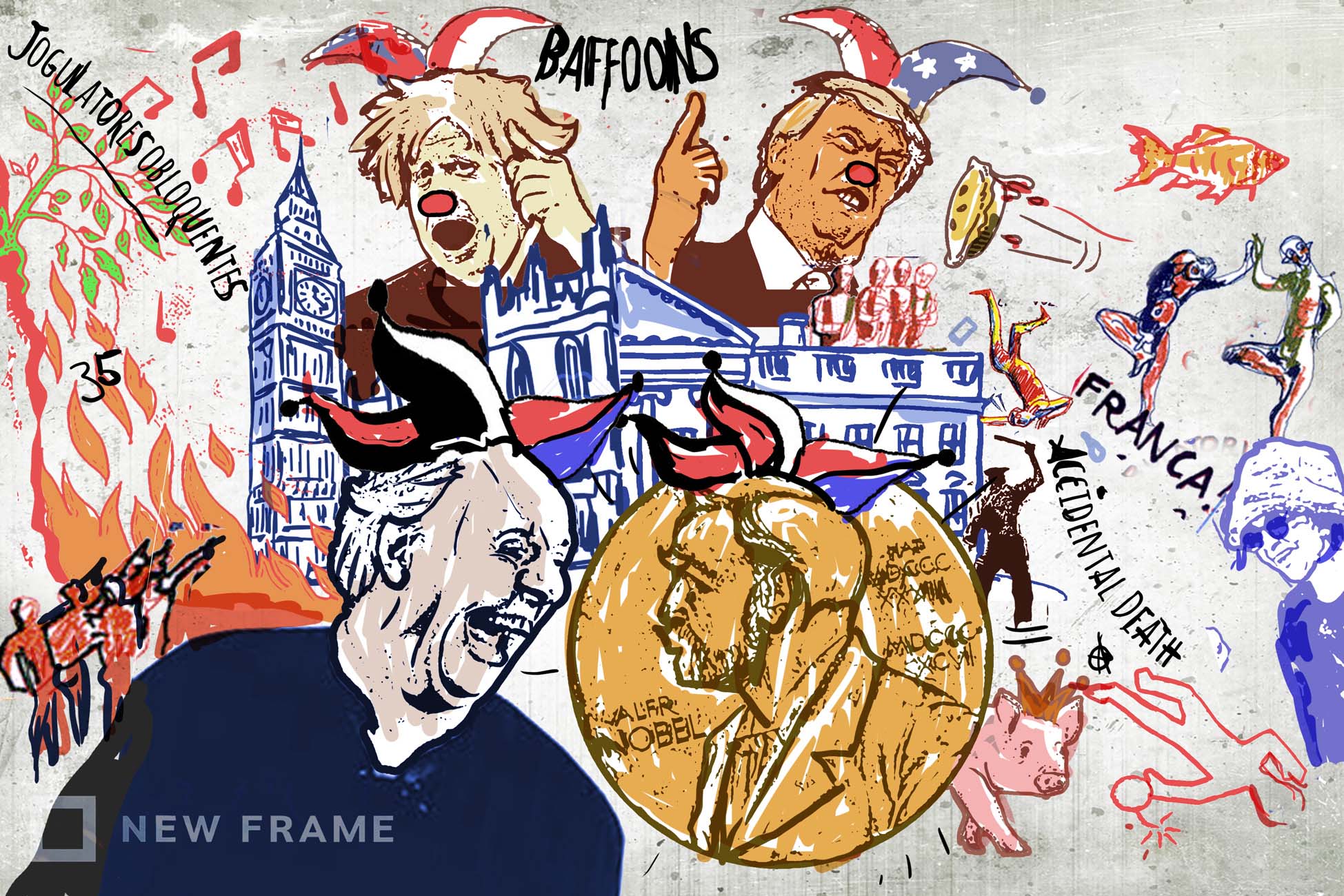

The world could do with many more true and proper jesters, seekers and tellers of truth through wit and satire, and with far fewer buffoons of the modern sort, a degraded version of the real buffone. Pre-eminent among modern jesters was the Italian farceur and political dramatist Dario Fo, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1997. The citation from the Nobel Academy noted that Fo “emulates the jesters of the Middle Ages in scourging authority and upholding the dignity of the downtrodden”.

Lies and obfuscations

Fo’s most famous work is probably Accidental Death of an Anarchist. In the explanation given by the authorities for the anarchist’s death, the play brings chillingly to mind South Africa’s catalogue of shameful lies and obfuscations in countless cases, including those of Steve Biko, Ahmed Timol and Neil Aggett.

It was no accident that Fo titled his Nobel Lecture Contra Jogulatores Obloquentes (Against Jesters Who Defame and Insult), a reference to the edict of that name issued by Emperor Frederick II in 1221 that declared “that anyone may commit violence against jesters without incurring punishment or sanction”. To go with his speech, Fo gave to the august Nobel audience a series of his drawings to illustrate the points he was making (some of these are represented in the illustration that accompanies this article).

In perhaps the most memorable performance ever at this event, Fo said:

“Friends of mine, noted men of letters, have in various radio and television interviews declared: ‘The highest prize should no doubt be awarded to the members of the Swedish Academy, for having had the courage this year to award the Nobel Prize to a jester.’ I agree. Yours is an act of courage that borders on provocation.

“It’s enough to take stock of the uproar it has caused: sublime poets and writers who normally occupy the loftiest of spheres, and who rarely take interest in those who live and toil on humbler planes, are suddenly bowled over by some kind of whirlwind.”

The most pointed observation he made, which accorded with his lifelong sense of fairness, equality and social justice, was:

“Above all others, this evening you’re due the loud and solemn thanks of an extraordinary master of the stage, little-known not only to you and to people in France, Norway, Finland … but also to the people of Italy. Yet he was, until Shakespeare, doubtless the greatest playwright of renaissance Europe. I’m referring to Ruzzante Beolco, my greatest master along with Molière: both actors-playwrights, both mocked by the leading men of letters of their times.

“Above all, they were despised for bringing on to the stage the everyday life, joys and desperation of the common people; the hypocrisy and the arrogance of the high and mighty; and the incessant injustice. And their major, unforgivable fault was this: in telling these things, they made people laugh. Laughter does not please the mighty.”