Text Messages | The parsing of Palestine

Twelve words in the 1917 Balfour Declaration had huge consequences for Palestine, but what of the earlier British-French agreement and Lawrence of Arabia’s role in the land grab?

Author:

4 April 2019

It is one of the shortest texts with the biggest and longest-lasting effects ever written. The Balfour Declaration, issued by foreign secretary Arthur James Balfour on behalf of the British government on 2 November 1917, is just one sentence. Its 67 words read as follows:

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

As the history of the past hundred years has shown, “the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine” have been severely prejudiced. Last week marked one year of Palestinian protests at the Gaza fence. It has been 12 months in which hundreds of Palestinian protesters have been killed and thousands injured by the Israel Defense Forces opening fire from the other side of the fence.

Related article:

Much of the blame for the roots of the current intractable situation is laid on Balfour. But he was just an instrument of British Imperial policy, a brief frontman for all the lurid ambitions of perfidious Albion. And, lurking behind Balfour and the empire maintenance men was an enigmatic, elusive figure, the very stuff of legend and an ultimate example of the Imperial hero: Colonel TE Lawrence, known far better then and now as Lawrence of Arabia.

Any discussion of Lawrence is almost immediately clouded by the pervasive image of the man created by one of the finest films ever made, David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia. The Irish actor Peter O’Toole played Thomas Edward Lawrence, one of the illegitimate sons of the Anglo-Irish baronet Thomas Chapman. The director, Lean, laid on all the elements of the Lawrence iconography: the flowing white Arab robes and headgear, the curved dagger on Lawrence’s belt, the desert, the camels, the heat, the oases, the fierce Arab guerrilla war against the armies of the Ottoman Turks.

Land grab

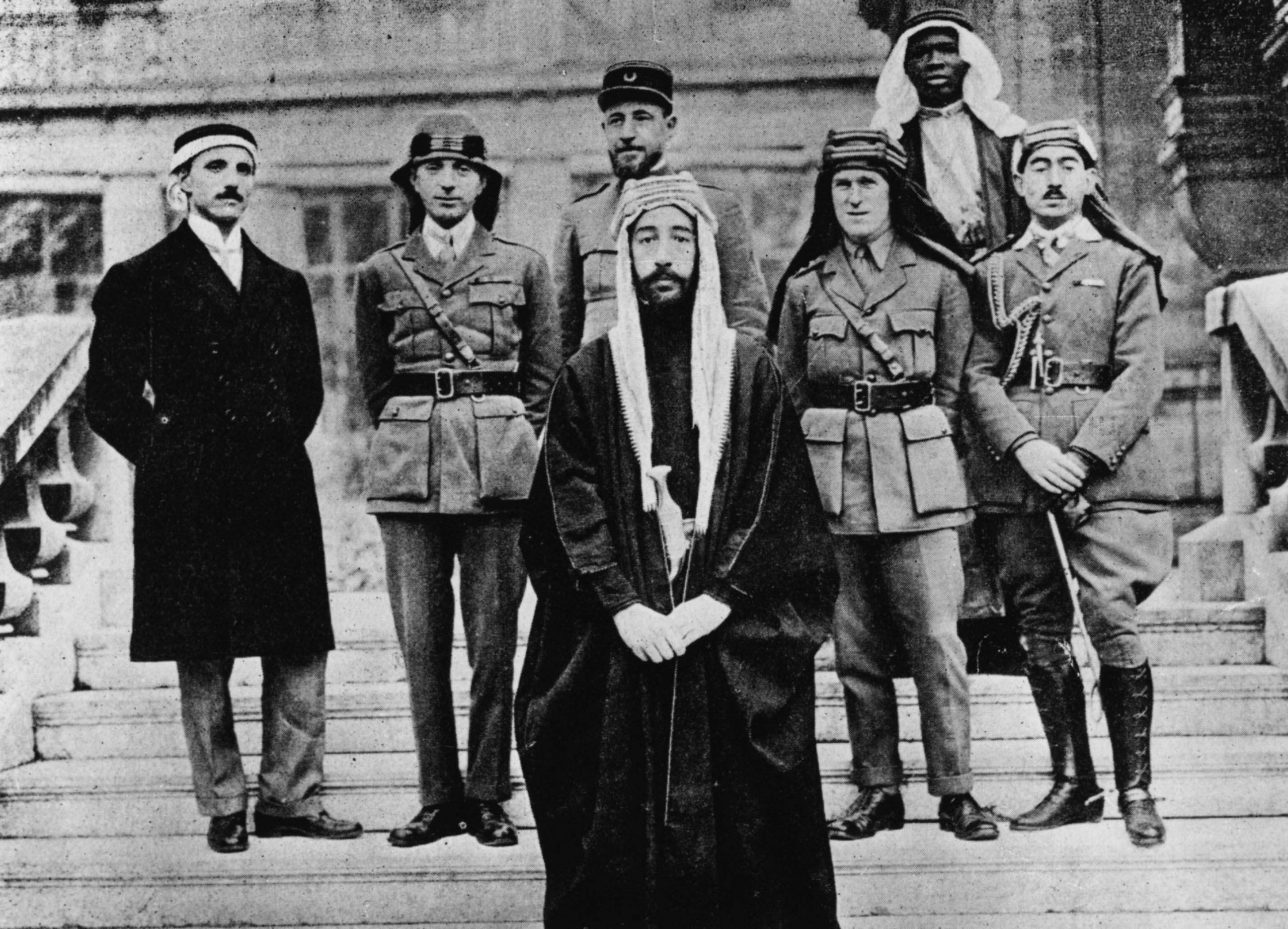

It was a war made under the aegis of the Grand Sherif of Mecca, Hussein, represented in the field by his son the Emir Feisal. It was also a war prosecuted by the Arabs partly at Lawrence’s instigation and ostensibly for the many Arab groupings in the huge region to win freedom from the Turks. Among other things, the Arabs were promised sovereignty in the liberated lands. In reality, the British and the French had already been deciding how to carve up the Ottoman Empire between themselves two years before the Balfour Declaration, through the Sykes-Picot Agreement.

Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Mark Sykes was a member of Parliament, an inveterate traveller and an authority on the Ottoman Empire. François George-Picot was an old-style career diplomat and a graduate of the influential schools of political science and law (Oxbridge for French diplomats). These two formulated an agreement under which Britain would grab land from southern Syria to what was then Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq), including Baghdad and Basra. France would get most of Syria and the Mosul enclave in Mesopotamia. Crucially, Palestine was designated under a form of international regime – a mandate of some kind.

Related article:

For all their efforts against the Turks, the Arabs would get almost nothing, and for them Damascus and with it all of Syria had always been the prize. The Arabs did not know about their exclusion until the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia and as part of their policy on hitherto secret agreements, made Sykes-Picot public knowledge. It could have ended the Arab Revolt but underhand British and French diplomacy, empty promises made verbally and on paper, and charm offensives to Hussein that included Sykes, Picot and Lawrence at various times, persuaded Hussein otherwise.

Tragically, Hussein even reassured Feisal by telegram – a means of communication the British were intercepting and unscrambling before transmitting onwards – that “The Allies are too great and high to have any confusion caused in the slightest thing of our agreements with them.”

Lawrence, invariably portrayed as a friend of the Arabs and a champion of their fight for independence and statehood, was deeply implicated in all of this. He knew about Sykes-Picot but never told either Feisal or Hussein. In public, later, he denied all prior knowledge of the carve-up.

The Balfour bombshell

Just as the Anglo-French initiative to placate Hussein was resolving favourably for the Allies, there came the Balfour bombshell. What did it mean? It seemed to contradict Sykes-Picot’s talk of a mandate in Palestine, declaring instead “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people”.

The consequences of those 12 words have been enormous. But leaving those aside, some questions suggest themselves. Had the British promised Palestine to the Arabs before the Balfour Declaration? What happened to the territorial butchery agreed to in Sykes-Picot? And what was Lawrence’s ultimate role? For some of the answers, one can turn to a book published 50 years ago, The Secret Lives of Lawrence of Arabia by Phillip Knightley and Colin Simpson (Thomas Nelson & Sons).

In answer to the first question, Knightley and Simpson disclose then recently released papers of a War Cabinet Eastern Committee meeting in London on 27 November 1918.

They quote Lord Curzon, Lord President of the Council, stating unequivocally: “The Palestine position is this. If we deal with our commitments, there is first the general pledge to Hussein in October 1915 under which Palestine was included in the areas to which Great Britain pledged itself that they should be Arab and independent in the future.”

In answer to the second, the Paris Peace Conference held at Versailles beginning in January 1919 saw the systematic erosion of promises to Hussein and Feisal. By the time it and the ensuing process ended in September 1919, Britain had got Mosul and its oilfields as well as mandates in Iraq, Trans-Jordan and Palestine. The French got what Monsieur Picot and they had always harboured: French troops displacing British forces in northern and western Syria and “a tacit admission by Britain of the French aim to establish eventually a mandate over the whole of Syria”. Lebanon was thrown in as well.

And what of Lawrence? On 27 September 1919 he wrote to Curzon offering to try and “make Feisal accept the Paris arrangement of last week reasonably”. Lawrence hoped, it seems, to safeguard Feisal in Syria and entrench him there to set up a British dominion, a scheme directed against the French rather than being pro-Arab.

Feisal reluctantly initialled the agreement arising from the Paris process and returned to Damascus. A year later the French army captured the city. Not quite 30 years later, the seizure of Palestine began.