Text Messages | Prize fight

Following the furore after the 2019 Nobel Prize for Literature was given to a genocide apologist, the Booker was eagerly awaited. But splitting the prize divided people even more.

Author:

17 October 2019

Everyone loves a winner they say, so how much more love would be lavished on two winners? Probably a whole lot less, to judge by the ambivalent and conflicted reception given to 2019’s Nobel laureates in literature and joint Booker Prize-winners.

This year’s Nobel for writers was always going to be difficult following a year – 2018 – in which the award was not made because of rape charges, subsequently proven, against the husband of one of the selection committee and other longstanding conflicts of interest. The idea had been to withhold the prize for a year and then hand out two in 2019 with a new, clean committee in place and the wrongs of the past addressed.

That the new committee chose to engarland Peter Handke, a fan of the Serbian mass murderer Slobodan Milošević and a denier of the Srebrenica massacre, sent a strange message about new beginnings. An Austrian playwright, Handke seemed furthermore very distant from what the Academy had been promising in the run-up to the award: moving away from its traditional “male-oriented” and “Eurocentric” perspective.

Related article:

The announcement of Handke’s win followed the naming as the 2018 winner of the Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk, who had won the Man Booker International Prize in 2018. Not a man, at least, but certainly from the heart of Europe. Sadly, Tokarczuk’s merits have scarcely been discussed because of the tsunami of shock and disgust let loose by Handke’s award.

Still, hope remained. The annual Booker Prize follows swiftly in the wake of the Nobel. For that, the Guildhall in London was the scene for something that should never have happened: the sharing of the Booker. After the previous splitting of the award in 1992, when Michael Ondaatje (The English Patient) and Barry Unsworth (Sacred Hunger) divided the honours, the Booker people specifically rewrote the rules for judges to ensure that no such tie ever occurred again. It’s worth noting that the only other dual award was to Nadine Gordimer (The Conservationist) and Stanley Middleton (Holiday) in 1974.

A policy of ‘consensus’

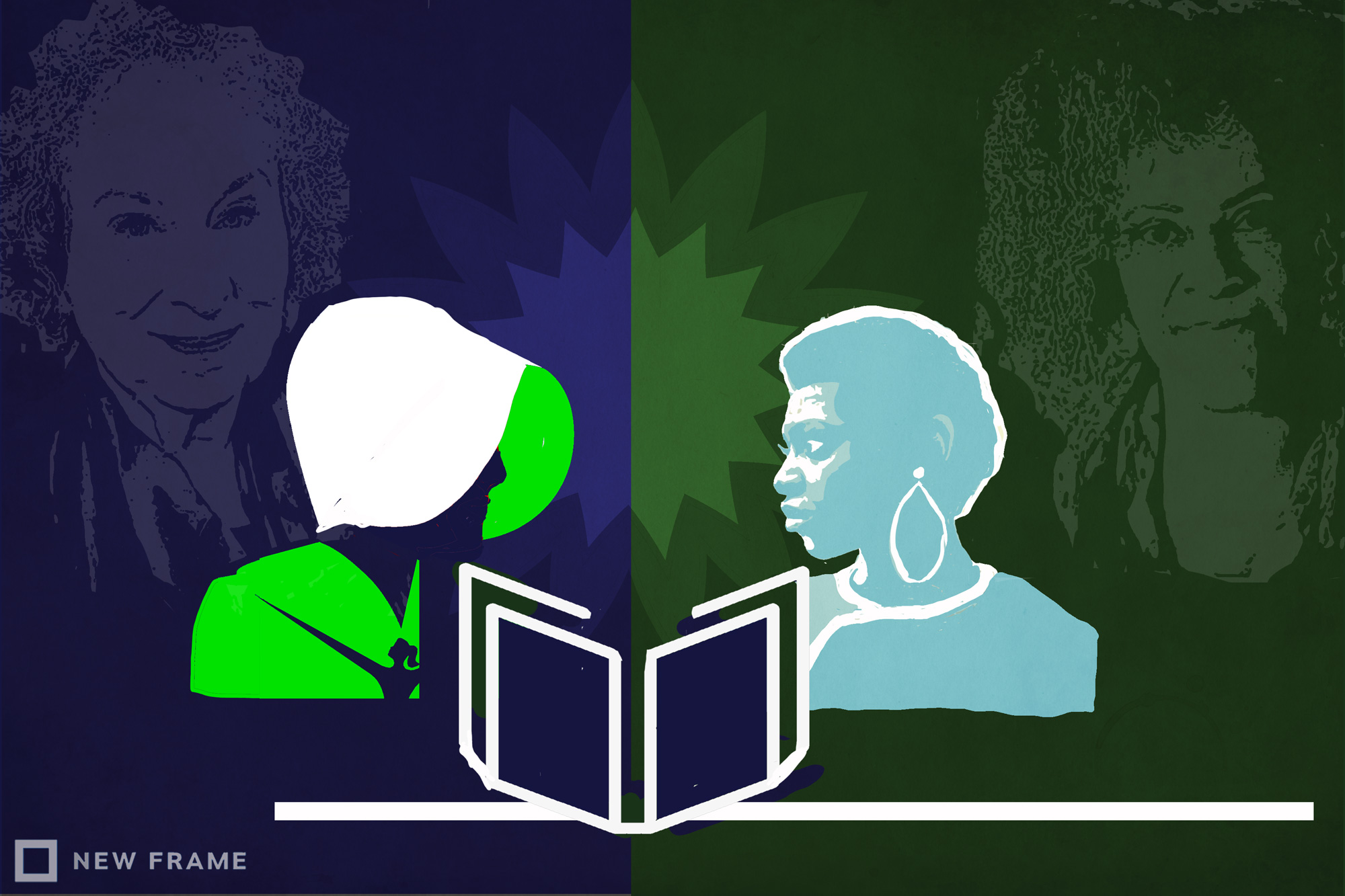

Clearly, those who recast the Booker rules underestimated the resolve and culture of consensus that the 2019 Booker judges brought to their task. Told twice by the administrator of the award and the Booker foundation’s chair that they could not name joint winners, they continued to demur, insisting on adhering to their policy of “consensus”. Worn down, the Booker folk relented. Margaret Atwood (The Testaments) and Bernardine Evaristo (Girl, Woman, Other) shared the money and the curious-looking physical award, which resembles a plastic menu holder.

Understandably, the announcement of the winners was merely the beginning of the fracas. In the days following 14 October, any number of criticisms have been levelled at the decision, the judges, even the two writers themselves. Conspiracy theorists have been more plentiful than toxic mushrooms in season. Regarding those, supporters of both writers have claimed that their woman has been patronised.

Through it all, Atwood and Evaristo have responded with the grace, intelligence and wisdom that make all their books, and not just these Booker-winning titles, an enlargement of the universe of the reader. In all the hubbub, that virtue appears to have been forgotten. That, and the very real consideration that only the meretricious write to win prizes. Writing is a competitive activity only insofar as the author wages merciless battle with the blank page.

Related article:

If it is otherwise, then the writer has fallen into the pitfall and pratfall of what Cyril Connolly memorably described as “the enemy of promise”: writing to win something material, a literary prize. His book of critical essays, Enemies of Promise (1938), would be worth rereading in the post-Booker tumult, especially bearing in mind the summation of his importance in The Oxford Companion to English Literature (sixth edition, revised, 2006): “Connolly’s favourite themes include the dangers of early success and the hazardous lure of literary immortality”.

Forty-five years on from The Conservationist, no one quibbles over its merits relative to Holiday or vice versa. It seems a reasonable bet that come 2064, The Testaments and Girl, Woman, Other will be warmly remembered and valued. They will endure, just as does the spectral presence in Gordimer’s great novel, so indelibly captured in its last paragraph:

“The one whom the farm received had no name. He had no family but their women wept a little for him. There was no child of his present but their children were there to live after him. They had put him away to rest, at last; he had come back. He took possession of this earth, theirs; one of them.”